Many meditators, healers and people of goodwill are attracted to the idea of distant healing — that in meditation, contemplation and prayer we can help relieve suffering and pain at a distance.

Many meditators, healers and people of goodwill are attracted to the idea of distant healing — that in meditation, contemplation and prayer we can help relieve suffering and pain at a distance.

But how exactly do we do this? I will share with you one golden rule, briefly list the most well-known techniques and then describe the strategy that I prefer.

First, The Golden Rule

This is simple: Distant healing must always be done in a relaxed, calm and loving way. Otherwise, you may be sending agitated vibrations and energies. In particular, you need to monitor that you do not have any neediness that there be a healing.

If we are needy for healing, then we radiate neediness. Not useful. So stay calm. The keynote is compassionate equanimity.

The most well-known distant healing strategies are:

- Kind thoughts

- Sending healing energy (keep to the golden rule above and check you are not interfering)

- Praying for help and intercessions from whichever tradition, gods, spirits, angels, saints, gurus, etc., who are in your culture.

Then there is the heart-opening strategy that I prefer to use.

I like it because it is relevant to both suffering and the causes of suffering. It is also realistic about the fact that some illnesses and distress are chronic and long term, and that death is an inevitability.

This strategy is simple. It is in a sense, a visualization, a calm expectation that the hearts open of those who are suffering.

In the same way, the hearts open of those who create suffering.

In a calm state of compassionate contemplation, bring any person or situation of suffering into your loving awareness.

May your heart be open. May your heart be open. May your heart be open.

When someone’s heart opens, they move into a different mood. They connect with the benevolent flow of the universe. Their emotions and minds become more accepting and kinder. Healing at all levels becomes more accessible. Space is created for waves of grace.

There are other ways of practicing this that may better suit you.

If for example you have a Christian background, then you may prefer some wording like this, which has the same effect: May the Christ within you awaken. Or May the Christ consciousness in you be fully awake.

From a Buddhist background, you might feel more at home with: May the Buddha within you awaken. Or May the Buddha consciousness in you be fully awake.

Of course, you are free to adapt the wording in whatever way works best for you.

Within the Buddhist tradition there is also the foundation prayer of Om Mani Padme Hum often translated as “the Jewel in the Lotus.” In many respects, this is a heart awakening mantra. Each of us is a lotus, a beautiful flower with stems beneath the water and roots deep into the earth. And within us is a jewel. Perceive it. Let it be fully present.

Again, this is congruent with the Hindu greeting of Namaste. I greet the soul within you. I greet your soul. I greet the Christ within you. The Buddha within you. The Goddess within you. All of these facilitate heart-opening.

Some people may prefer to work with the chakra system. You can sense-visualize-imagine the love petals of someone’s heart chakra opening with compassion and wisdom.

I use this heart-opening approach when, in meditation, I send healing to the dictators and politicians who are oppressing their peoples. I sense their hearts opening. May your heart be open. I greet your soul.

Similarly, I use this strategy when contemplating those who are suffering with pain and fear.

May your hearts be open. I greet your soul. Om mani padme hum.

Softly, gently, empathically, connect with suffering and sense heart-opening.

As always, you as an individual practitioner can explore and feel your way into the approach that is authentic for you.

Remember, too, to practice basic health and safety. Your fuel, inspiration and safety come from your connection with spirit, by whatever name you call it. At the end of any healing, bring your focus fully home to your own body and close your energy field like a flower at night closing its petals.

I honor and respect activists who work on the front lines to relieve suffering and create safe space for all life to grow and fulfill.

I also honor and support the meditators, contemplatives and prayer-workers who work with distant healing.

About the Author:

William Bloom is Britain’s leading author and educator in the mind-body-spirit field with over thirty years of practical experience, research and teaching in modern spirituality. He is founder and co-director of The Foundation for Holistic Spirituality and the Spiritual Companions project. Visit www.williambloom.com

Original article here

We may be slowly returning to our offices (more or less), but the strains of the pandemic are hardly over. As we enter a transitional stage after almost two years of trauma and strain, more than ever we need ways to refresh our energies, calm our anxieties, and nurse our well-being. One potentially powerful intervention is rarely talked about in the workplace: The cultivation of experiences of awe. Like gratitude and curiosity, awe can leave us feeling inspired and energized. It’s another tool in your toolkit and it’s now attracting increased attention due to more rigorous research.

We may be slowly returning to our offices (more or less), but the strains of the pandemic are hardly over. As we enter a transitional stage after almost two years of trauma and strain, more than ever we need ways to refresh our energies, calm our anxieties, and nurse our well-being. One potentially powerful intervention is rarely talked about in the workplace: The cultivation of experiences of awe. Like gratitude and curiosity, awe can leave us feeling inspired and energized. It’s another tool in your toolkit and it’s now attracting increased attention due to more rigorous research. About 20 years ago, working for National Geographic, and with a grant from the National Institute on Aging, I started identifying and studying the longest-lived people, those who are in what we called the world’s Blue Zones. These are people who have eluded heart disease, diabetes, dementia, and several types of cancer.

About 20 years ago, working for National Geographic, and with a grant from the National Institute on Aging, I started identifying and studying the longest-lived people, those who are in what we called the world’s Blue Zones. These are people who have eluded heart disease, diabetes, dementia, and several types of cancer. Have you ever gotten into bed at the end of the day and realised that you haven’t spoken out loud to anyone since the day before? Or simply found yourself feeling completely and utterly alone?

Have you ever gotten into bed at the end of the day and realised that you haven’t spoken out loud to anyone since the day before? Or simply found yourself feeling completely and utterly alone? “Those who are emotionally lonely will find it difficult to improve things without tackling the root of the problem,” says Dr. Spelman. “Emotional loneliness is not circumstantial but, rather, comes from within.”

“Those who are emotionally lonely will find it difficult to improve things without tackling the root of the problem,” says Dr. Spelman. “Emotional loneliness is not circumstantial but, rather, comes from within.” But situational loneliness doesn’t just arise in those who relocate alone, as social media editor Sarah discovered when she moved countries with her partner. Sarah left her Sydney home in March 2017 to join her partner in London, where he had arrived a month earlier to start a new job and find the pair a home to live in — although she admits that “didn’t mean it was smooth sailing”.

But situational loneliness doesn’t just arise in those who relocate alone, as social media editor Sarah discovered when she moved countries with her partner. Sarah left her Sydney home in March 2017 to join her partner in London, where he had arrived a month earlier to start a new job and find the pair a home to live in — although she admits that “didn’t mean it was smooth sailing”. “It was a really bewildering, lonely time,” she says. “The jump of being plonked into a huge arts school, in just one of hundreds of halls of residence in a sprawling city I didn’t understand, made me retreat into myself and I struggled to make friends in the face of it all.

“It was a really bewildering, lonely time,” she says. “The jump of being plonked into a huge arts school, in just one of hundreds of halls of residence in a sprawling city I didn’t understand, made me retreat into myself and I struggled to make friends in the face of it all. It’s probably been a long time since you lay on your back in the grass, looked up and wondered, Why is the sky blue? Or since you took the time to consider a question as difficult as, Where does the universe begin, and where does it end?

It’s probably been a long time since you lay on your back in the grass, looked up and wondered, Why is the sky blue? Or since you took the time to consider a question as difficult as, Where does the universe begin, and where does it end?

“I don’t like resting,” I tell her. “I get listless and sad and feel a failure.” She is not surprised. “For some people, rest is almost uncomfortable. It’s almost as if their psyche fights back against it because of the new sensation.” She would never, she says, recommend a three-day silent retreat to a completely frazzled patient. “For someone who is actively burned out, that’s almost traumatic.”

“I don’t like resting,” I tell her. “I get listless and sad and feel a failure.” She is not surprised. “For some people, rest is almost uncomfortable. It’s almost as if their psyche fights back against it because of the new sensation.” She would never, she says, recommend a three-day silent retreat to a completely frazzled patient. “For someone who is actively burned out, that’s almost traumatic.”

This is no surprise to Dalton-Smith. Analysing data from her quiz during the pandemic, she saw “a huge uptick in the number of people who were experiencing sensory rest deficits”. People confined to the house with small children in particular, she says, were exposed to constant noise and even some adults “irritated each other to death. That non-stop hum of somebody talking in the background causes you to get agitated. That’s what sensory overload does to us.”

This is no surprise to Dalton-Smith. Analysing data from her quiz during the pandemic, she saw “a huge uptick in the number of people who were experiencing sensory rest deficits”. People confined to the house with small children in particular, she says, were exposed to constant noise and even some adults “irritated each other to death. That non-stop hum of somebody talking in the background causes you to get agitated. That’s what sensory overload does to us.”

We are often told to place ourselves in other people’s shoes – but our empathy is rarely as accurate as we think it is.

We are often told to place ourselves in other people’s shoes – but our empathy is rarely as accurate as we think it is.  Epley’s team asked pairs of participants, who had not met previously, to discuss questions such as, “If a crystal ball could tell you the truth about yourself, your life, your future or anything else, what would you want to know?”.

Epley’s team asked pairs of participants, who had not met previously, to discuss questions such as, “If a crystal ball could tell you the truth about yourself, your life, your future or anything else, what would you want to know?”. All over the world, people are awakening to the fact that we are more than bones and flesh. We sense that there is more to life than what we see. The word “consciousness” is losing its unreachable meaning, and we look for ways to go inside ourselves and find inner peace.

All over the world, people are awakening to the fact that we are more than bones and flesh. We sense that there is more to life than what we see. The word “consciousness” is losing its unreachable meaning, and we look for ways to go inside ourselves and find inner peace.

There is so much angst in the air these days that we may all be feeling more sensitive, exhausted or even more despondent than usual. So much so, that I feel a lot of folks are at the end of their tether, overwhelmed by the vast onslaught of confusing emotions and free-floating anxiety in the telluric atmosphere.

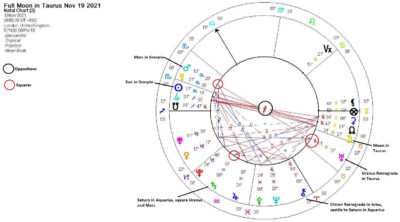

There is so much angst in the air these days that we may all be feeling more sensitive, exhausted or even more despondent than usual. So much so, that I feel a lot of folks are at the end of their tether, overwhelmed by the vast onslaught of confusing emotions and free-floating anxiety in the telluric atmosphere. On Friday, November 19th, there will be a partial Lunar Eclipse in Scorpio-Taurus.

On Friday, November 19th, there will be a partial Lunar Eclipse in Scorpio-Taurus. The one message anger can have for us is that our Soul Core is alerting us to some person, situation or thing that violates our sense of Self, or our core values. As such, anger is then your friend, and an ally in helping you in choosing and activating healthy boundaries. In a climate such as we have now, people’s right to say “NO!” is even being taken away. To someone experiencing physical, mental or sexual abuse, we would be appalled if someone were denied the inherent right to say “NO!, that is does not feel good and I will resist!” This is when anger can give us the courage to stand up for ourselves and by saying “no” we are saying “yes” to what feels right and good for us.

The one message anger can have for us is that our Soul Core is alerting us to some person, situation or thing that violates our sense of Self, or our core values. As such, anger is then your friend, and an ally in helping you in choosing and activating healthy boundaries. In a climate such as we have now, people’s right to say “NO!” is even being taken away. To someone experiencing physical, mental or sexual abuse, we would be appalled if someone were denied the inherent right to say “NO!, that is does not feel good and I will resist!” This is when anger can give us the courage to stand up for ourselves and by saying “no” we are saying “yes” to what feels right and good for us.