Did you know that worrying is like a rocking chair?

It gives you something to do, but it doesn’t get you anywhere.

Excessive worrying is exhausting and can become a great waste of time and energy. It puts your mind in overdrive and distracts you from doing the more important things, as well as preventing you from having a healthy, happy life.

Most people worry on a regular basis, as a natural part of life. However, the worry habit can become problematic when it becomes too intense and chronic. Some people even worry about worrying. When you are plagued by thoughts that are persistent and out of control, they end up causing interference and paralysis in your daily life.

The bad news is that constant worrying eventually takes a toll on your emotional and physical health, as well as your self-esteem, relationships, and career. When you keep hitting the panic button, the stress response is triggered, which leads to fear, then more stress and anxiety, and then more worry. An endless worry cycle is created.

The good news is that worrying is a mental habit that can be broken. You can train your brain to stay calm and remain positive. You are in charge of your thoughts and imagination. How you choose to use your mind is your responsibility. Do you continue to misuse your imagination and keep focusing on the negative or do you choose to switch to the positive?

The reason most people worry too much is often rooted in fear – ultimately a fear of something happening that cannot be controlled. When we anticipate something negative happening in the future, it is based on irrational thoughts. We are afraid of the worst-case scenario, as we have allowed our minds to wander too far on the negative side.

9 Practical Tips To Minimize Worrying

- Learn to distinguish between what you can control in life and what you can’t. The things you can change need an action plan with a list of concrete steps you can take to solve the problem. And for the things you cannot change, you need to learn acceptance. The Serenity Prayer sums it up perfectly: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

- Recognize your trigger points. Find out the source of your worries and gain a clearer picture of what’s driving them. Your worries will start losing power, and you will start regaining control of your mind. Self-awareness is the first step to changing your mindset.

- Re-frame your thoughts and change your perspective. Instead of saying, “I can’t handle this,” become more self-confident and start believing that you can handle it. Make a list of the negative messages you are feeding your mind and replace them with positive affirmations. Make sure you challenge those thoughts. No amount of worrying will make life any more predictable.

- Break the worry cycle by limiting your worrying time. Schedule a worry time each day to keep the worry contained and prevent it from contaminating your whole day. Sit down for 15 minutes and make a list of all the things you want to worry about, and then proceed to worry about them. At the end of the exercise, you will come to the realization that worrying is futile. You can become more mindful of your thoughts and where you place your energy. Choose to focus on what really matters in your life and become more productive.

- Get up and move. Take a 20-minute walk. Stretch out and do some yoga. Exercise is a productive activity that can interrupt your worries and shift your body’s energy. It releases endorphins, which get rid of the tension and break the cycle.

- Breathing exercises, meditation and relaxation techniques also interrupt your train of thoughts and calm the body’s response to stress. This dynamic trio helps relax your body, guide your thoughts, and keep them from getting caught up in worries.

- Ground yourself in the present. Become mindful of your thoughts and activities. Make time to unplug and take a look at the bigger picture. Ask yourself if what you are worrying about is really going to matter in five years from now. If not, let it go and don’t spend more than five minutes worrying about it. If it does matter, then make a list of one or two things you can do now to solve the problem. Keep in mind, you may not resolve the whole problem right then and there, but at least your thoughts will be clearer and calmer, and you will be able to move forward by focusing on what matters instead of worrying about things that don’t really matter.

- Stop overthinking and dwelling on your worries by finding a healthy distraction like reading a good book, watching a funny movie, listening to great music, taking up hobbies that you enjoy, or doing something different, such as trying a new recipe.

- Build a support network. Enlist the help of your trusted friends and family. By sharing your thoughts and tuning into your feelings, it can help you process them as you feel supported. In some cases, chronic worry can be a symptom of GAD or generalized anxiety disorder. You can seek the help of a therapist or join a support group. Don’t keep your worries to yourself. This will cause them to build up and become overwhelming.

Next time you catch yourself worrying, instead of pressing the panic button, reach for the pause button and ask yourself, “What’s important now?” Coach Lou Holtz came up with the acronym W.I.N. or What’s Important Now. This enables you to prioritize your decisions, choices and actions. The antidote for worrying is to maintain calm, clarity, and focus. Also, by having a grateful mind, you can look for the positive in every situation.

Strengthen your mind by learning to turn off those worrying thoughts and regain control. Look at life from a less fearful and more balanced perspective.

Original article here

Every once in a while I wonder how my life can get any better. And then it does! Over and over again. How is it that that can happen without much effort on my part to make it so? Here are my #lovinglife suggestions for joy seekers everywhere.

Every once in a while I wonder how my life can get any better. And then it does! Over and over again. How is it that that can happen without much effort on my part to make it so? Here are my #lovinglife suggestions for joy seekers everywhere.

One of the simplest ways we can help our bodies thrive and prevent over-eating is to change the order in which we eat our food. Reaching for the bread basket or bowl of crisps at the start of a meal results in a rapid increase in blood glucose levels and a subsequent insulin response. This will likely leave you feeling tired, hungry and irritable just a few hours later. This is because glucose is rapidly absorbed from starchy foods, and this is even quicker on an empty stomach.

One of the simplest ways we can help our bodies thrive and prevent over-eating is to change the order in which we eat our food. Reaching for the bread basket or bowl of crisps at the start of a meal results in a rapid increase in blood glucose levels and a subsequent insulin response. This will likely leave you feeling tired, hungry and irritable just a few hours later. This is because glucose is rapidly absorbed from starchy foods, and this is even quicker on an empty stomach. The colours in our plants are there thanks to chemicals called polyphenols, also known as phytonutrients. These chemicals are produced by plants to protect themselves against environmental stressors, including drought, cold weather, hot weather, insects and parasites. A great example of this is the dark red colour of the oranges which grow in the foothills of Mount Etna in Sicily, where the nights are very cold and the days are very hot and dry.

The colours in our plants are there thanks to chemicals called polyphenols, also known as phytonutrients. These chemicals are produced by plants to protect themselves against environmental stressors, including drought, cold weather, hot weather, insects and parasites. A great example of this is the dark red colour of the oranges which grow in the foothills of Mount Etna in Sicily, where the nights are very cold and the days are very hot and dry. Before doing the ZOE programme, I thought my breakfast of muesli with skimmed milk was exactly what I needed for the day ahead. I soon learned that this breakfast, washed down with a glass of orange juice, pushed my blood sugar to diabetic levels and I quickly changed the menu. Adding mixed nuts and seeds to plain natural yoghurt with some polyphenol-rich berries is a great way to enjoy a nutritious breakfast that won’t spike your blood sugar.

Before doing the ZOE programme, I thought my breakfast of muesli with skimmed milk was exactly what I needed for the day ahead. I soon learned that this breakfast, washed down with a glass of orange juice, pushed my blood sugar to diabetic levels and I quickly changed the menu. Adding mixed nuts and seeds to plain natural yoghurt with some polyphenol-rich berries is a great way to enjoy a nutritious breakfast that won’t spike your blood sugar. In modern times, clocks underpin everything people do, from work to school to sleep. Timekeeping is also the invisible structure that makes modern infrastructure work. It forms the foundation of the high-speed computers that conduct financial trading and even the GPS system that pinpoints locations on Earth’s surface with unprecedented accuracy.

In modern times, clocks underpin everything people do, from work to school to sleep. Timekeeping is also the invisible structure that makes modern infrastructure work. It forms the foundation of the high-speed computers that conduct financial trading and even the GPS system that pinpoints locations on Earth’s surface with unprecedented accuracy. Not getting enough sleep is detrimental to both your health and productivity. Yawn. We’ve heard it all before. But results from one study impress just how bad a cumulative lack of sleep can be on performance. Subjects in a lab-based sleep study who were allowed to get only six hours of sleep a night for two weeks straight functioned as poorly as those who were forced to stay awake for two days straight. The kicker is the people who slept six hours per night thought they were doing just fine.

Not getting enough sleep is detrimental to both your health and productivity. Yawn. We’ve heard it all before. But results from one study impress just how bad a cumulative lack of sleep can be on performance. Subjects in a lab-based sleep study who were allowed to get only six hours of sleep a night for two weeks straight functioned as poorly as those who were forced to stay awake for two days straight. The kicker is the people who slept six hours per night thought they were doing just fine. If you think you sleep seven hours a night, as one out of every three Americans does, it’s entirely possible you’re only getting six.

If you think you sleep seven hours a night, as one out of every three Americans does, it’s entirely possible you’re only getting six.

The brain seems to get it just right. “This is in a cool sweet spot in between,” said Eric Shea-Brown, a mathematical neuroscientist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the study. “It’s a balance between being smooth and systematic, in terms of mapping like inputs to like responses, but other than that, expressing as much as possible about the input.”

The brain seems to get it just right. “This is in a cool sweet spot in between,” said Eric Shea-Brown, a mathematical neuroscientist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the study. “It’s a balance between being smooth and systematic, in terms of mapping like inputs to like responses, but other than that, expressing as much as possible about the input.” In the summer of 2021, I experienced a cluster of coincidences, some of which had a distinctly supernatural feel. Here’s how it started. I keep a journal and record dreams if they are especially vivid or strange. It doesn’t happen often, but I logged one in which my mother’s oldest friend, a woman called Rose, made an appearance to tell me that she (Rose) had just died. She’d had another stroke, she said, and that was it. Come the morning, it occurred to me that I didn’t know whether Rose was still alive. I guessed not. She’d had a major stroke about 10 years ago and had gone on to suffer a series of minor strokes, descending into a sorry state of physical incapacity and dementia.

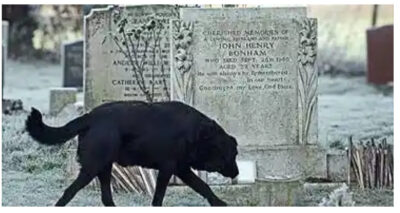

In the summer of 2021, I experienced a cluster of coincidences, some of which had a distinctly supernatural feel. Here’s how it started. I keep a journal and record dreams if they are especially vivid or strange. It doesn’t happen often, but I logged one in which my mother’s oldest friend, a woman called Rose, made an appearance to tell me that she (Rose) had just died. She’d had another stroke, she said, and that was it. Come the morning, it occurred to me that I didn’t know whether Rose was still alive. I guessed not. She’d had a major stroke about 10 years ago and had gone on to suffer a series of minor strokes, descending into a sorry state of physical incapacity and dementia. While some coincidences seem playful, others feel inherently macabre. In 2007, the Guardian journalist John Harris set out on ‘an intermittent rock-grave odyssey’ visiting the last resting places of revered UK rock musicians. About halfway through, he went to the tiny village of Rushock in Worcestershire to gather thoughts at the headstone of the Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham, who died at the age of 32 on 25 September 1980, after consuming a prodigious quantity of alcohol. A Guardian photographer had visited the grave a few days earlier to get a picture to accompany the piece. It was, writes Harris, ‘an icy morning that gave the churchyard the look of a scene from The Omen’ and, fitting with one of the key motifs of that film, the photographer was ‘spooked by the appearance of an unaccompanied black dog, which urinates on the gravestone and then disappears’. ‘Black Dog’ (1971) happens to be the title of one of the most iconic songs in the Led Zeppelin catalogue.

While some coincidences seem playful, others feel inherently macabre. In 2007, the Guardian journalist John Harris set out on ‘an intermittent rock-grave odyssey’ visiting the last resting places of revered UK rock musicians. About halfway through, he went to the tiny village of Rushock in Worcestershire to gather thoughts at the headstone of the Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham, who died at the age of 32 on 25 September 1980, after consuming a prodigious quantity of alcohol. A Guardian photographer had visited the grave a few days earlier to get a picture to accompany the piece. It was, writes Harris, ‘an icy morning that gave the churchyard the look of a scene from The Omen’ and, fitting with one of the key motifs of that film, the photographer was ‘spooked by the appearance of an unaccompanied black dog, which urinates on the gravestone and then disappears’. ‘Black Dog’ (1971) happens to be the title of one of the most iconic songs in the Led Zeppelin catalogue. Jung was the first to bring coincidences into the frame of psychological enquiry, and made use of them in his analytic practice. He offers an anecdote about a golden beetle as an illustration of synchronicity at work in the clinic. A young woman is recounting a dream in which she was given a golden scarab, when Jung hears a gentle tapping at the window behind him and turns to see a flying insect knocking against the windowpane. He opens the window and catches the creature as it flies into the room. It turns out to be a rose chafer beetle, ‘the nearest analogy to a golden scarab that one finds in our latitudes’. The incident proved to be a transformative moment in the woman’s therapy. She had, says Jung, been ‘an extraordinarily difficult case’ on account of her hyper-rationality and, evidently, ‘something quite irrational was needed’ to break her defences. The coincidence of the dream and the insect’s intrusion was the key to therapeutic progress. Jung adds that the scarab is ‘a classic example of a rebirth symbol’ with roots in Egyptian mythology.

Jung was the first to bring coincidences into the frame of psychological enquiry, and made use of them in his analytic practice. He offers an anecdote about a golden beetle as an illustration of synchronicity at work in the clinic. A young woman is recounting a dream in which she was given a golden scarab, when Jung hears a gentle tapping at the window behind him and turns to see a flying insect knocking against the windowpane. He opens the window and catches the creature as it flies into the room. It turns out to be a rose chafer beetle, ‘the nearest analogy to a golden scarab that one finds in our latitudes’. The incident proved to be a transformative moment in the woman’s therapy. She had, says Jung, been ‘an extraordinarily difficult case’ on account of her hyper-rationality and, evidently, ‘something quite irrational was needed’ to break her defences. The coincidence of the dream and the insect’s intrusion was the key to therapeutic progress. Jung adds that the scarab is ‘a classic example of a rebirth symbol’ with roots in Egyptian mythology. I have come far in my life, farther than I ever dreamed was even possible. And yet my dreaming continues, urging me ever onward.

I have come far in my life, farther than I ever dreamed was even possible. And yet my dreaming continues, urging me ever onward.