It starts without warning—or rather, the warnings are there, but your ability to detect them exists only in hindsight. First you’re sitting in the car with your son, then he tells you: “I cannot find my old self again.” You think, well, teenagers say dramatic stuff like this all the time. Then he’s refusing to do his homework, he’s writing suicidal messages on the wall in black magic marker, he’s trying to cut himself with a razor blade. You sit down with him; you two have a long talk. A week later, he runs home from a nighttime gathering at his friend’s apartment, he’s bursting through the front door, shouting about how his friends are trying to kill him. He spends the night crouching in his mother’s old room, clutching a stuffed animal to his chest. He’s 17 years old at this point, and you are his father, Dick Russell, a traveler, a former staff reporter for Sports Illustrated, but a father first and foremost. It is the turn of the 21st century.

Up until this point, your son, Frank, has been a fully functional kid, if somewhat odd. An eccentric genius, socially inept yet insightful—perhaps an artist in the making, you thought. Now you are being told your son’s quirks stem from pathology, his mystic phrases are not indications of creative genius but of neural networks misfiring. You sit with Frank as he receives his diagnosis, schizophrenia, and immediately all sorts of associations flood into your head. In the United States, a diagnosis of schizophrenia often means homelessness, joblessness, inability to maintain close relationships, and increased susceptibility to addiction. Your son is now dangling off this cliff. So you hand him over to the doctors, who prescribe him antipsychotics, and when he balloons up to 300 pounds, and they tell you he’s just being piggish, you believe them.

Had Frank been living someplace else, things may have turned out differently. In some countries, schizophrenics hold down jobs at five times the rates of American schizophrenics. In others, symptoms are interpreted as unusual powers.

Dick and his son tried a variety of treatments over 15 years, some more effective than others. Then, unexpectedly, the pair turned in a very different direction, beginning a journey that Dick now likens to a “torch-lit passageway through a long dark tunnel.” By sharing his story, he hopes to help others find this passageway—but he’s aware some of it sounds crazy. For instance: He now believes Frank might be a shaman.

Certain structures and regions in the brain are thought to be particularly important in constructing our sense of self. One is the meeting place between the two middle lobes of the brain: the temporal lobe, which translates sight and hearing into language, emotion, and memory, and the parietal lobe, which integrates all five senses to locate the body in space. This region, called the temporoparietal junction, or TPJ, assembles information from these and other lobes into a mental representation of one’s physical body, and its place in space and time. It also plays a role in what’s called theory of mind, the ability to recognize your thoughts and desires as your own and to understand that other people have mental states that are separate from yours.

When the TPJ is altered or disturbed, putting oneself together becomes difficult and sometimes painful. Body Dysmorphic Disorder, characterized by extreme preoccupation with imagined physical defects, is thought to arise from faulty TPJ interplay. Researchers see atypical TPJ activity in Alzheimer’s patients, Parkinson’s patients, and amnesiacs.

Don’t take my devils away, because my angels may flee, too.”

Schizophrenia is intimately related to TPJ messiness. It affects theory of mind; schizophrenic patients often believe that others harbor animosity toward them, and when they perform mental tasks related to theory of mind, their TPJ activity either spikes or crashes. Researchers have induced the kind of ghostly visions and out-of-body experiences that some schizophrenics experience, simply by stimulating the TPJ with electrodes. The psychiatrist Lot Postmes calls this “perceptual incoherence,” noting that the jumbled assortment of sensory information leads to an untethering of ego: “a normal sense of self, as a feeling of unitary entity, the ‘I,’ that owns and authors its thoughts, emotions, body, and actions.”

Having a dissolved self can make it immensely hard for a schizophrenic person to present a coherent picture of themselves to the world, and to relate to other, more gelled selves. “Schizophrenia is a disease whose main manifestations are sufferers’ [diminished] abilities to engage in social interactions,” says Matcheri S. Keshavan, a psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School and an expert on schizophrenia. And yet, ironically, people with schizophrenia need others just as much as socially capable people do, if not more. “A problem with schizophrenia is however much they want [social interactions], they often lose the skills needed for navigating them,” Keshavan says.

This craving for social connection puts schizophrenic people at stark contrast to people diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). In 2008, Bernard Crespi, a biologist at Simon Fraser University, in Canada, and Christopher Badcock, a sociologist at the London School of Economics, theorized that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia were opposite sides of the same coin. “Social cognition,” they wrote, is “underdeveloped in autism, but hyper-developed to dysfunction in psychosis (schizophrenia).” In other words, where an autistic person’s sense of self is cripplingly narrow, schizophrenics’ selves are cripplingly expansive: They believe they are many people at once, and see motive and meaning everywhere.

As difficult as they may be to live with, these perceptual distortions can make schizophrenic people more creative. Schizophrenics tend to see themselves as more imaginative than others, and to embark on more artistic projects.5 Numerous people with schizophrenia have said that their creative thoughts and delusions come from the same source: Poet Rainer Maria Rilke refused treatment for his visions, saying “don’t take my devils away, because my angels may flee, too.” The author Stephen Mitchell, who translated many of Rilke’s works, put it this way: “He was dealing with an existential problem opposite from the one that most of us need to resolve: Whereas we find a thick, if translucent, barrier between self and other, he was often without even the thinnest differentiating membrane.”

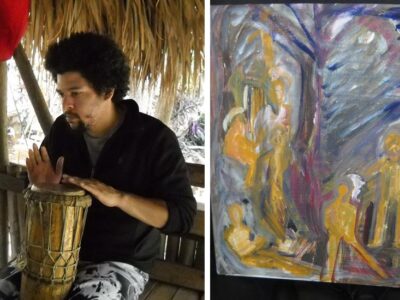

Frank Russell reported feeling something similar. “He told me he feels like a mirror, reflecting what’s inside people,” his father, Dick, writes. “It was hard for him to sort out what’s him and what’s them.” And Frank, Dick reports, is highly creative. He draws, paints, and welds. He invents languages out of made-up “hieroglyphs” and archetypal symbols. He composes long poems about god and racial tension, and has won numerous awards for his poetry at school.

And yet Frank’s strange preoccupation with symbols, his belief he could become Chinese or shift into a bear, made social interaction awkward and difficult. He spent the 10 years following his initial diagnosis mostly isolated, largely incapable of forming long-lasting relationships or joining group activities. Apart from doctors, the only consistent people in Frank’s life were his parents. That was before they met Malidoma Patrice Some.

According to the World Health Organization, schizophrenia is universal. “So far, no society or culture anywhere in the world has been found free from … this puzzling illness,” states a 1997 report. A diagnosis of schizophrenia considers the combination of five symptoms, as well as their impact and duration: 1) Delusions, 2) Hallucinations, 3) Disorganized speech, 4) Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and 5) Negative symptoms like affective flattening (restricted emotional expressiveness), alogia (diminished capacity for speech), or avolition (lack of initiative). But the WHO cautions that these criteria are to be taken with a grain of salt—“current operationalized diagnostic systems, while undoubtedly very reliable, leave the question of validity unanswered in the absence of external validating criteria,” the report notes. Diagnosis “should therefore be considered a provisional tool,” set to organize treatment plans while “leav[ing] the door open to future developments.”

Terms of diagnosis are in constant flux. “It keeps changing over time,” says Keshavan. “We’re doing research to develop better biomarkers, but it’s still complicated.” Robert Rosenheck, a psychiatrist at Yale University who studies the cost efficiency of various treatment models for schizophrenia, goes even further. “Usually with medicine, the whole idea is that you have illnesses with a medical basis, a physiological basis. We don’t have that for schizophrenia.”

If the broken-down person does not have a community around him or her, he or she may fail to heal.

Adding to the complexity, schizophrenia looks different across cultures. Several studies by the World Health Organization have compared outcomes of schizophrenia in the U.S. and Western Europe with outcomes in developing nations like Ghana and India. After following patients for five years, researchers found that those in developing countries fared “considerably better” than those in the developed countries. In one study, nearly 37 percent of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia in developing countries were asymptomatic after two years, compared to only 15.5 percent in the U.S. and Europe. In India, about half of people diagnosed with schizophrenia are able to hold down jobs, compared to only 15 percent in the U.S.

Many researchers have theorized that these counterintuitive findings stem from a key cultural difference: developing countries tend to be collectivistic or interdependent, meaning the predominant mindset is community-oriented. Developed countries, on the other hand, are usually individualistic—autonomy and self-motivated achievement are considered the norm. Other variables in developing countries can, at times, complicate this dichotomy—for instance, the relative scarcity of medication, and other cultural factors such as stigma. However, one study of “sociocentric” differences between ethnic minority groups within the U.S. found results suggesting that “certain protective aspects of ethnic minority culture”—namely, the prevalence of two collectivist values, empathy and social competence—“result in a more benign symptomatic expression of schizophrenia.”

“Take a young man with schizophrenia who’s socially unable to engage,” Keshavan says. “In a collectivistic culture, he’s still able to survive in a joint family with a less fortunate brother or cousin … he’ll feel supported and contained. Whereas in a more individualistic society, he’ll feel let go, and not particularly included. For that reason, schizophrenia tends to be highly disabling [in individualistic countries].” Individualist cultures also “[diminish] motivation to acknowledge illness and seek help from others, whether from therapists or in clinics or residential programs.” notes Russell Schutt, a leading expert on the sociology of schizophrenia.

Outcomes across cultures may also be affected by differences in the patients themselves. In 2012, Shihui Han, a neuroscientist at Peking University, asked volunteers from a traditionally interdependent country (China) and a more independent one (Denmark) to think about various people, all while monitoring activity in the TPJ. In both groups, the TPJ lit up when they attempted to infer other peoples’ thought processes, a theory of mind task. But in Chinese participants, the TPJ also activated when they thought about themselves. In Danish people, their medial prefrontal cortex, which the researchers used to measure the degree of self-reflection, lit up more than in the Chinese participants. In essence, Chinese subjects’ sense of self was blurrier on average, in a way that directly affected the area of the brain implicated in schizophrenic symptoms.

In Han’s study, the average TPJ activity levels of people from the traditionally interdependent country looked closer to those of schizophrenic patients. Other studies, including Chiyoko Kubayashi Frank at the School of Psychology at Fielding Graduate University in Santa Barbara, have theorized that diminished activity in the TPJ area in Japanese adults and children during theory of mind tasks “might represent the demoted sense of self-other distinction in the Japanese culture.”12This shows up in how both populations perceive the world differently: People from collectivistic countries are more likely to believe in God,13and to attend to context in images, while people from individualistic countries are likely to ignore context in favor of the image’s primary focus. This implies schizophrenics are less likely to be doubted or stigmatized for their visions in collectivistic cultures, and thus, they are less likely to feel what Schutt calls “socially-generated stress”—which, he notes, “has biological effects that can exacerbate symptoms of mental illness.”

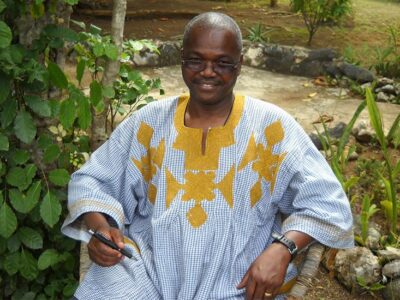

Malidoma is from a collectivist society. Born into the Dagara tribe in Burkina Faso, he is the grandson of a renowned healer, who travels around the world but is based in the U.S. Malidoma sees himself as a bridge between his culture and the United States, existing to “bring the wisdom of our people to this part of the world.” Malidoma’s “career”—he chuckles at the term—is some combination of cultural ambassador, homeopath, and sage. He travels the country doing rituals and consultations, writing books, and giving speeches. He has three master’s degrees and two doctorates from Brandeis University. Sometimes he calls himself a “shaman,” because people know what that means (sort of) and it’s similar to his title back in Burkina Faso—a titiyulo, one who “constantly inquires with other dimensions.”

Malidoma is from a collectivist society. Born into the Dagara tribe in Burkina Faso, he is the grandson of a renowned healer, who travels around the world but is based in the U.S. Malidoma sees himself as a bridge between his culture and the United States, existing to “bring the wisdom of our people to this part of the world.” Malidoma’s “career”—he chuckles at the term—is some combination of cultural ambassador, homeopath, and sage. He travels the country doing rituals and consultations, writing books, and giving speeches. He has three master’s degrees and two doctorates from Brandeis University. Sometimes he calls himself a “shaman,” because people know what that means (sort of) and it’s similar to his title back in Burkina Faso—a titiyulo, one who “constantly inquires with other dimensions.”

Dick first heard about Malidoma through James Hillman, a Jungian psychologist whose biography he was writing, at a time when Frank’s treatment had stagnated. For most of his 20s, Frank lived in group homes. His favorite, called Earth House, was a privately owned home, and far more structured than his other group homes. It offered classes, provided leadership opportunities, and fostered a loving, caring environment. Frank made close friends and acted in plays. Dick was elated: For the first time since Frank fell ill, his life was full of friends and purpose.

Both shamans and schizophrenic people believe they have magical abilities, hear voices, and have out-of-body experiences.

It’s because of reactions like this (and because communities help remind patients to take their meds) that community has emerged as a necessary dimension of schizophrenia treatment in Western medicine. In a review of 66 studies, researchers at the University of Santiago, in Chile, found that “community-based psychosocial interventions significantly reduced negative and psychotic symptoms, days of hospitalization, and substance abuse.”15 Patients were more likely to take medication regularly, hold jobs, and have friends. They were also less likely to feel ashamed of themselves. Similar results have been found in the U.S.

But for Frank and Dick, there was a problem. A spot in Earth House cost $20,000 per quarter—a price Dick, a lifelong journalist, could not afford for very long. After 16 months of Earth House subsidized by friends and family, he decided to stop “postponing the inevitable.” Dick drove Frank drove back to Boston and put him in a less structured group home, where, over time, he seemed to deteriorate.

It was around then, in 2012, that Dick decided to seek out Malidoma; first speaking with him over the telephone, and then meeting with him in Ojai, a small town outside of Los Angeles; then, a year later, meeting him in Jamaica, this time bringing Frank along.

When Malidoma first met Frank one evening over dinner in Jamaica, he recognized the man’s likeness to himself instantly. “The connection we had was immediately clear,” he says. As soon as schizophrenic met shaman, the latter shook his head and clasped Frank’s hands as if they’d known each other for years. He told Dick that Frank was “like a colleague!” Malidoma believes that Frank is a U.S. version of a titiyulo; in fact, there is a version of a titiyulo in pretty much every culture, he says. He also believes that one cannot choose to become a titiyulo: It happens to you. “Every shaman started with a crisis similar to those here who are called schizophrenic, psychotic. Shamanism or titiyulo journeys begin with a breakdown of the psyche,” he says. “One day they’re fine, normal, like everyone else. The next day they’re acting really weird and dangerously toward themselves and the village”—seeing and hearing things that aren’t there, acting paranoid, shouting.

When this happens, the Dagara people begin a collective effort to heal the broken-down person; one marked by loud rituals involving dancing and cheering and with an underlying current of celebration. Malidoma remembers watching his sister go through it. “My sister was screaming into the night,” he says, “but people were playing around her.” Usually, the uncontrollable breakdowns last about eight months, after which effectively new people emerge. “You have to go through this radical initiation where you can become the larger than life person the community needs for their own benefit, you know?” If the broken-down person does not have a community around him or her, Malidoma says, he or she may fail to heal. He believes this is what happened to Frank.

Had Frank been born into the Dagara tribe, and experienced the same breakdown at age 17 that led him to run from his friend’s apartment, Malidoma tells me that the community would have immediately rallied around him, performing the same rituals that his sister experienced. Following this intervention, his tribe members would begin the work of healing Frank and re-integrating him back into the community; once he was ready, he’d receive a prominent position. “He’d be known as a man of spirit, who’d be able to provide insight into the deep problems of the people around them,” he says.

No longer simply a madman, he is a painter and a poet, a traveler and a friend.

Malidoma is not the first person to posit a link between shamanism and schizophrenia. The psychiatrist Joseph Polimeni wrote an entire book on the subject, called Shamans Among Us. There, Polimeni noted several connections: Both shamans and schizophrenic people believe they have magical abilities, hear voices, and have out-of-body experiences. Shamans become shamans in their late teens to early 20s, about the same age range that schizophrenia is typically diagnosed (17-25) in men. Both schizophrenics and shamans are more commonly male than female. And the prevalence of shamans (say one per 60-150 people, the estimated size of most early human communities) is similar to the global prevalence of schizophrenia (around 1 percent).

This theory isn’t widely supported. Critics note that shamans appear to be able to enter and exit their shamanic states at will, while schizophrenic people have no control over their visions. But Robert Sapolsky, a neurobiologist at Stanford University, has hypothesized a similar and more widely accepted theory: Many spiritual leaders, like shamans and prophets, may have “schizotypal personality disorder.” People with this diagnosis are often relatives of schizophrenics who possess milder versions of some symptoms, such as peculiar ways of speaking or “metamagical” thinking, which is linked to creativity and high IQ. This profile sounds like it may fit Malidoma, who never experienced a “break” but whose brother and sister both did.

Whether or not Frank’s psychosis would have made him a shaman in another time or place, three central factors are present in the Dagara tribal intervention (early intervention, community, and purpose) that parallel the three factors that Keshavan, Schutt, Rosenheck, and others cite as complements to pharmaceutical drugs: early intervention, community support, and employment. Dick had perhaps missed the boat on the Dagara initiation ceremony, but Malidoma advised Dick to incorporate other aspects of his approach into his son’s life, including rituals and other purposeful activities.

After returning from Jamaica back home to Boston, Frank kept in touch with Malidoma by phone. He and Dick traveled to the homes and clinics of various alternative healers, who met Frank’s delusions with warmth and encouragement. Dick started to encourage his son more, too. When Frank asked Dick to include some of his thoughts in the memoir he was writing, including the idea that “one additive to beer is molten dolphin sweat,” Dick dutifully complied. Rather than provoke more delusional behavior in Frank, Dick says, these experiences have had a “grounding effect.” They show him he has friends and family who respect who he is and all that he’s capable of. “If some of [Franklin’s] dreams exist only in the imaginative realm, so be it,” Dick wrote in his memoir, My Mysterious Son: A Life-Changing Passage Between Schizophrenia and Shamanism. “I’ve learned the importance of this for him.”

The effects have been profound. Years ago, before meeting Malidoma, Frank was less motivated to seek social encounters. At 37 he took trips to New Mexico and Maine, and took classes in mechanical engineering. Today, he is a remarkably inventive jazz pianist. His room is filled with his paintings and metalwork, rife with archetypal imagery and hieroglyphic languages of his own creation.

He’s not cured. He still occasionally hears voices and harbors delusions. And he still lives in a group home. But he has been able to cut his medication in half again. He has lost weight, and his diabetes has become asymptomatic. He’s more courteous, alert, and engaged, his father and doctors say. He still has bad days, but they are fewer and farther between.

Perhaps the biggest factor motivating Frank’s improvement, however, has been the shift in how he views himself. No longer simply a madman, he is a painter and a poet, a traveler and a friend, an African and an American, a welder and a student.

And, most recently, a shaman. In February 2018, Frank, Dick, and Frank’s mother visited Malidoma’s tribe in Burkina Faso, where Frank took part in healing rituals. He spent four weeks living in the village before returning home to Boston in early March. Dick and Malidoma are loath to disclose details of the ceremony, and say only that Frank’s response to the rituals gave them hope.

The experience also shifted Dick’s perception. “I never expected to be conducting spiritual water rituals at the ocean,” he said. But that’s what he did, and, in the course of helping his son recover, he found that his own views of sickness and health had shifted. “To the extent that psychosis involves the creation of an alternate reality, the goal is to enter that world. There’s also a recognition that the world we think of as real is actually infused with aspects of the Other—that there is a mysterious impenetration or even an underlying unity.”

As for traditional medicine’s take? To the best of Dick’s knowledge, scientists haven’t studied a case exactly like Frank’s.

Original article here

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.