Who are you?” said the Caterpillar.

Alice replied, rather shyly, “I-I hardly know, Sir, just at present-at least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have been changed several times since then.”

“What do you mean by that?” said the Caterpillar, sternly. “Explain yourself!”

“I can’t explain myself, I’m afraid, Sir,” said Alice, “because I am not myself, you see.”

– Alice in Wonderland

Are things feeling a bit ‘odd’ to you of late? Has your dream life picked up considerably, but you can’t make heads or tails about what they might mean? Felt spacey, light-headed, or dizzy, or like you’re walking in a dream or a starring in a cartoon. Maybe you’ve fallen down the rabbit hole, and are wondering around in Wonderland? Well, that’s the psychic and astrological space between the eclipse that just occurred on April 30th, and the one coming up on May 16th. It’s also being amped up in other ways, which I’ll get to momentarily.

Another thing about the space we’re currently traveling through isn’t something else to be wary of, or apprehensive about. Despite the headlines, or the gossip, not all that is happening on our planet is a cause for concern or over-reaction. If some of my previous articles have put you on high alert about certain aspects of the current situation we are experiencing or witnessing, I have not shared from a place of trying to create fear or anxiety, but from a place of love and a desire to inform and empower you.

We are all changing and being changed at such an accelerated pace that some disorientation is perfectly normal. Considering the level and intensity of the times we are living through, inside a predominantly digital environment, it will affect our perceptions and our assumptions or judgments about those perceptions. This is the nature of digital…it is binary, and either something is on or off, 0 or 1, left or right, up or down, right or wrong.

There isn’t very much room or latitude for both/and, or neutrality. Hence all the polarization and atomization of our cultures. Many of our institutional structures are founded on the dualistic model, and it has permeated human consciousness ever since the beginnings of “civilization”. Prior to that, our orientations were predominantly inclusive. Our ancestors weren’t striving for unity, they were already living it to a certain degree. They intuitively understood their place within the fabric of Nature and the heavens. They had no illusions about the intimate interplay between the elements, the environment and themselves. They accepted all of it as something they were part and parcel of.

Since those long-forgotten times, history has happened, and we have lost some very precious aspects of our humanity. As a result, we created religions and other spiritual systems with rules to try understanding the world around us and come to grips with the main 5 questions before all of humanity – who am I, why am I here, where am I, what do I do with this, and what does it all mean? Being orphaned from our original primordial consciousness has divorced us from knowing and thrown us into bicameral confusion via the dualistic mind. We are predominantly mental creatures these days, and our intuitive and instinctual natures are either dormant, suppressed or extremely subservient to the orientation we have to the mind created self. The digital age has not only accelerated our propensity to living in a disembodied state almost 24/7, but it has also influenced human consciousness into a desire to emulate or merge with technology itself. From where I sit, this situation is unsustainable and an evolutionary dead end.

The astrology of our times is mirroring this situation back to us, hoping that we’ll catch on and connect the dots before we are totally subsumed into a trance-like hive mind. The event of the partial Solar Eclipse on 30th of April introduced us to some encouraging energies and laid out before us some challenges as well. Uranus conjunct the Sun-Moon at 10 Taurus, along with a conjunction of Jupiter, Venus, and Mars in the late degrees of Pisces, has emphasized our dissociative state of awareness while at the same time trying to awaken us to our predicament of being orphaned from our true and natural sentient state of beingness. Hence the dreamy sort of stumbling around effect some of you may be encountering. However, as I mentioned earlier, the astrology is merely reflecting an existing situation. The causative factors are numerous and are triggered and amplified by the transiting aspects in astrology.

Factor 1: The Schumann Resonance has been off the charts since April 29th. This is most likely in response to the series of X-Class flares our star has been generating off and on since mid-April.

Factor 2: Geomagnetic storms are more frequent. (See Solar activity)

Factor 3: Collective or consensus reality – the dominator culture is ramping things up on several fronts locally and globally: the situation in the Ukraine, hyper-inflationary policies and hidden price-gouging putting downward pressure on the middle class and poor. The Oil Giants are currently celebrating bumper profits in the 1st fiscal quarter of 2022. Celebrity distractions (Heard-Depp hearings), and politics as usual round out the list.

Factor 4: The pandemic mentality hasn’t gone away entirely, while at the same time a growing body of evidence is pointing out that the responses to the whole thing may be making things worse many times over. In the U.K. the highest number of new cases called Covid-19 (or one of the variants) are among those who have received both jabs plus one and even two boosters.

The Merry Month of May has plenty of activation points to cover, so here’s the menu:

May 10th – Mercury turns stationary retrograde at 4 degrees and 51 minutes of Gemini Time: 12:48pm BST. Please, please, please, back up your data on all your digital devices well ahead of the 10th.

May 11th – Jupiter ingress into Aries at 00:44am BST

May 13th – The Sun conjuncts the North Node at 22 degrees of Taurus

May 16th – Full Moon Total Lunar Eclipse at 25 degrees of Taurus, conjunct the Lunar Nodes at 22 Taurus. Chiron and Venus are conjunct at 14 plus of Aries, Mars is conjunct Neptune at 23 plus degrees of Pisces, and Saturn at 24 Aquarius is still square to the Lunar Nodes.

All of the above is a significant chronology to be sure, but the main event is the bookend eclipse on May 16th. This completes, or rather initiates, the first eclipse pattern for 2022.

In a nutshell this Lunar Eclipse will set the tone for the next six months or so. Taurus-Scorpio is about security and acquisition mixed with desire and power, around food, shelter, sex, money, and VALUES! Uranus is too far away from this eclipse to add much to it, but he’s already had his input back on April 30th. I’d look for this eclipse to bring more to the light of awareness about how we are all being conned out of our humanity by the promises of a shiny new utopia that openly states that, “we will own nothing and be happy.” That quote is from Klaus Schwab and the World Economic Forum’s stated goal to digitize humanity and our institutions into a global control grid.

We will also be asked to examine our acquired values and dig deeper to find our true values…those ones that our ancestors held as sacred: love, empathy, embodied living, compassion, cooperation, mutual respect, and a universal recognition of the oneness of all Life, a Life with Divine origination.

What may thwart or distort this will be the Mars-Neptune conjunction in Pisces. More distortion of the truth, or facts…take your pick. Twisting realities to suit a narrow agenda. Obliterating information and data crucial to personal or collective decision-making via censorship and state security public relations statements. Think the “memory hole” from Orwell’s book “1984”. You may be told that something you saw somewhere, no matter how briefly, never existed in the first place. With everything and everyone logged into the “cloud”, making data disappear is a relatively easy affair. More celebrity dramas or entertainment distractions will proliferate. Meanwhile the Saturn effect on the Nodes will provide a backdrop of the same “you need to do what everyone else is doing for the good of all” messaging. Maybe Covid restrictions will resurface. We’ll see.

The buffer will be provided by Chiron meeting Venus in Aries. Chiron in Aries is symbolic of the right of being an individual…an individuated and unique being, and that this a divine birth right that no other can abrogate or take away from you, unless you acquiesce to it being done. Imagine a lone individual standing up to collective power, and you get the idea. The “Tank Man” photo from the time of the democracy movement in China that brought on the tragedy of the massacre at Tiananmen Square in Beijing comes to mind. One person, standing in front of a line of battle tanks, and refusing to move out of the way, is a compelling example of the symbology of Chiron’s transit through Aries. Adding Venus into the mix only amplifies the message to embrace and love our uniqueness and individuality, and everyone else’s right to the same thoroughly and totally.

This configuration of Venus-Chiron will help us to understand the meaning of the sudden reversal, or intended reversal, of the controversial “Roe versus Wade” Supreme Court ruling in a preliminary brief that was leaked earlier this week. This intended revelation has galvanized women to speak out against the ongoing efforts of the patriarchal forces to claw back women’s rights, and everyone’s divine right of sovereignty and choice in all matters, including what you allow or don’t allow to happen with one’s body.

With the Nodes in Scorpio-Taurus, one can also see the interplay of the issues about fertility, sexual preferences, childbearing, motherhood, and childrearing coming up at this juncture. Is there a war on women? Of course, there has been…for millennia. Also, a war on our biology and sexuality. The heritage and user’s manual for the conservative patriarchal mindset is rooted in the Judeo-Christian doctrines. Those belief systems originated with A.I. Not the A.I. of Silicon Valley fame, the alien A.I. that helped to foster the monotheistic father-God religions. This scenario is clearly delineated in the Gnostic gospels, known as the Nag Hammadi Codices. It is plain to see that these issues have become politicized over the past 30-40 years. Politics and religion do not have carte blanche to impose anything on anyone that does not align with the inner values of the individual. Venus-Chiron will be about self-knowledge and self-love.

It now appears to be a war on humanity itself, or at the very least, the organic version of us. The original organic human being is seen by transhumanists as messy, imperfect, and fatally flawed…and prone to illness and death. This perception is birthed and fostered by A.I. (artificial intelligence), and with our culture becoming ever more ensconced in a digital framework it will only hasten the demise of our species, as we have known it.

In summary, I feel this eclipse cycle will usher in a resurgence of individual willpower, a will to not just resist an imposed order from the past, but to work in concert with a wider global awareness that if we can stand up for ourselves adequately, we can work in cooperation with others more effectively. The gaps are widening in many areas of our human family, and it will be necessary to remember that differences of opinion of mindset does not obviate the reality of our inherent oneness or divine origins.

In summary, I feel this eclipse cycle will usher in a resurgence of individual willpower, a will to not just resist an imposed order from the past, but to work in concert with a wider global awareness that if we can stand up for ourselves adequately, we can work in cooperation with others more effectively. The gaps are widening in many areas of our human family, and it will be necessary to remember that differences of opinion of mindset does not obviate the reality of our inherent oneness or divine origins.

Love, a realistic love, based on the timeless spiritual values of respect for the choices and sovereignty of others, also includes the knowing that we are the author(ity) in our lives. As such, the agendas of others cannot include domination of the “other”, in any form. The time of centralized authority is already past, but the progenitors of it have refused to acknowledge it and continue to pursue an insane course of activity. In other words, respect others’ choices, but do not allow other’s choices to take a higher priority than that. Don’t betray yourself or your values out of fear or obligation.

Which brings us full circle to the subject line of this blog, Alice’s conversation with the Caterpillar. No matter how selfish it might feel to your or my ego, completely accepting and celebrating Who We Are, as we are right now, is essential. Once we realize that knowing we relax into trusting ourselves, and our own guidance. All deeper knowing comes from this step towards caring for the Self unconditionally. This is the crux of becoming self-actualized, and it is the primary purpose of our life’s journey, both here and beyond. For example, you could choose to realize that judging yourself about your flaws is not a productive strategy for joy and inner peace. Difficulty in accepting the bits we judge as wrong in ourselves is made a thousand times worse by accepting the judgment of others, or an outer authority, as valid. This is the origin of guilt and shame…an outer authority declaring your fatal flaws, your original sins, and us believing it!

Between now and the bookend Eclipse of May 16th, take some steps to loving the totality of you, just as you are in this moment. Doing mirror work is a useful tool for such an exploration. Conscious deep breathwork is another. One of my favourites is long walks in Nature, where I can breathe deeply into my body and feel the walls between myself, my form and the outer natural world dissolve. It’s an “always on” love affair…with Nature. Allow Her in. This is the message of the North Node in Taurus too…to honour the Mother inside each one of us.

We have never been alone, and never will be. What an adventure!

About the Author:

Isaac George is an internationally recognized intuitive mentor/coach, evolutionary astrologer, conscious channel, self-published author and musician. After a life-altering spontaneous kundalini awakening in 1994 he explored various healing modalities, including hypnotherapy and Reiki. In 1998 he began spontaneously channeling Archangel Ariel and other dimensional intelligences.

Originally from the United States, Isaac currently resides in the UK and offers Spiritual Mentoring sessions and programs and Evolutionary Astrology consultations.

Sara Inés Lara, leader of Colombia-based bird conservation organization Fundación ProAves, got her first taste of conservation’s potential more than 30 years ago. She grew up in one of the most biodiverse places in the world, seeking refuge in the forests, mountains, and pools of the Andes. Then, in 1998, she learned about the yellow-eared parrot.

Sara Inés Lara, leader of Colombia-based bird conservation organization Fundación ProAves, got her first taste of conservation’s potential more than 30 years ago. She grew up in one of the most biodiverse places in the world, seeking refuge in the forests, mountains, and pools of the Andes. Then, in 1998, she learned about the yellow-eared parrot. Women for Conservation also faced resistance from its peers in the environmental world. Lara remembers other conservation leaders telling her that working with women was nice, but it was not a priority. Whenever she spoke about the link between a growing population, increasing poverty, and environmental impacts, she was told to avoid talking about population.

Women for Conservation also faced resistance from its peers in the environmental world. Lara remembers other conservation leaders telling her that working with women was nice, but it was not a priority. Whenever she spoke about the link between a growing population, increasing poverty, and environmental impacts, she was told to avoid talking about population. “People think of laws being so objective and serious, and almost separate from the social norms,” says investigative climate journalist Amy Westervelt. “But it’s really just a handful of people’s beliefs that have gotten baked into law.”

“People think of laws being so objective and serious, and almost separate from the social norms,” says investigative climate journalist Amy Westervelt. “But it’s really just a handful of people’s beliefs that have gotten baked into law.” And it might just be working. She says the proof is in the pushback.

And it might just be working. She says the proof is in the pushback.

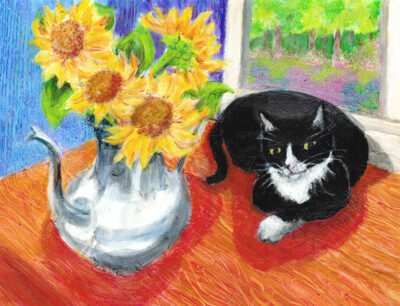

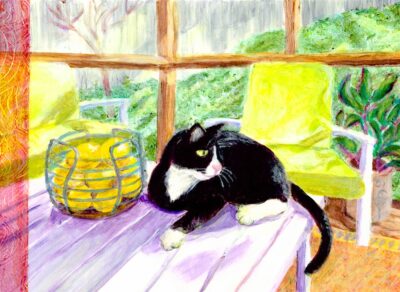

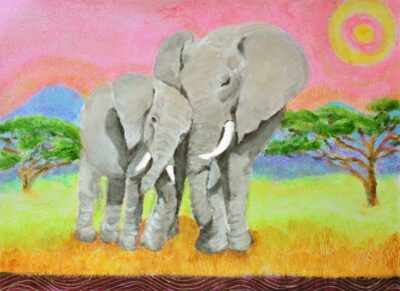

I am an Atlanta-based artist. I paint on watercolor paper using a process of layering acrylic paint and scratching back to reveal unique colors and textures in my paintings. The smooth absorbent paper allows me to bring out the light of the page and to play with layering colors.

I am an Atlanta-based artist. I paint on watercolor paper using a process of layering acrylic paint and scratching back to reveal unique colors and textures in my paintings. The smooth absorbent paper allows me to bring out the light of the page and to play with layering colors.

Last year, I met an extremely gifted medium in California: Allie Barkalow. If you don’t know what a medium is, it’s a person who communicates with spirits from the other side. I heard about Allie from my dear friend, Carolyn Miller, who is a psychic and known for her amazing tarot and aura photography readings. Carolyn told me that Allie is one of the best psychics she knows, and I figured if she’s anything like Carolyn I had to meet her.

Last year, I met an extremely gifted medium in California: Allie Barkalow. If you don’t know what a medium is, it’s a person who communicates with spirits from the other side. I heard about Allie from my dear friend, Carolyn Miller, who is a psychic and known for her amazing tarot and aura photography readings. Carolyn told me that Allie is one of the best psychics she knows, and I figured if she’s anything like Carolyn I had to meet her. Moldavite is a member of the tektite group, a glassy mixture of silicon dioxide, aluminum oxide and other metal oxides, with a hardness of 5.5 to 6. Its crystal system is amorphous. The color of most specimens is a deep forest green, though some pieces are pale green and others, especially those from Moravia, are greenish brown. A few rare gem grade pieces are almost an emerald green.

Moldavite is a member of the tektite group, a glassy mixture of silicon dioxide, aluminum oxide and other metal oxides, with a hardness of 5.5 to 6. Its crystal system is amorphous. The color of most specimens is a deep forest green, though some pieces are pale green and others, especially those from Moravia, are greenish brown. A few rare gem grade pieces are almost an emerald green. People who hold moldavite for the first time most often experience its energy as warmth or heat, usually felt first in one’s hand and then progressively throughout the body. In some cases, there is an opening of the heart chakra, characterized by strange (though not painful) sensations in the chest, an upwelling of emotion and a flushing of the face. This has happened often enough to have earned a name — the “moldavite flush.” Moldavite’s energies can also cause pulsations in the hand, tingling in the third eye and heart chakras, a feeling of light-headedness or dizziness, and occasionally the sense of being lifted out of one’s body. Most people feel that moldavite excites their energies and speeds their vibrations, especially for the first days or weeks, until they become acclimated to it.

People who hold moldavite for the first time most often experience its energy as warmth or heat, usually felt first in one’s hand and then progressively throughout the body. In some cases, there is an opening of the heart chakra, characterized by strange (though not painful) sensations in the chest, an upwelling of emotion and a flushing of the face. This has happened often enough to have earned a name — the “moldavite flush.” Moldavite’s energies can also cause pulsations in the hand, tingling in the third eye and heart chakras, a feeling of light-headedness or dizziness, and occasionally the sense of being lifted out of one’s body. Most people feel that moldavite excites their energies and speeds their vibrations, especially for the first days or weeks, until they become acclimated to it. Withdrawing my hands reluctantly from the slowly spinning bowl, I watched its uneven sides slowly come to a stop, wishing I could straighten them out just a little more. I was in the ancient pottery town of Hagi in rural Yamaguchi, Japan, and while I trusted the potter who convinced me to let it be, I can’t say I understood his motives.

Withdrawing my hands reluctantly from the slowly spinning bowl, I watched its uneven sides slowly come to a stop, wishing I could straighten them out just a little more. I was in the ancient pottery town of Hagi in rural Yamaguchi, Japan, and while I trusted the potter who convinced me to let it be, I can’t say I understood his motives. Wabi, which roughly means ‘the elegant beauty of humble simplicity’, and sabi, which means ‘the passing of time and subsequent deterioration’, were combined to form a sense unique to Japan and pivotal to Japanese culture. But just as Buddhist monks believed that words were the enemy of understanding, this description can only scratch the surface of the topic.

Wabi, which roughly means ‘the elegant beauty of humble simplicity’, and sabi, which means ‘the passing of time and subsequent deterioration’, were combined to form a sense unique to Japan and pivotal to Japanese culture. But just as Buddhist monks believed that words were the enemy of understanding, this description can only scratch the surface of the topic. It is the inevitable mortality embound in nature, however, that is key to a true understanding of wabi-sabi. As author Andrew Juniper notes in his book Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence, “It… uses the uncompromising touch of mortality to focus the mind on the exquisite transient beauty to be found in all things impermanent”. Alone, natural patterns are merely pretty, but in understanding their context as transient items that highlight our own awareness of impermanence and death, they become profound.

It is the inevitable mortality embound in nature, however, that is key to a true understanding of wabi-sabi. As author Andrew Juniper notes in his book Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence, “It… uses the uncompromising touch of mortality to focus the mind on the exquisite transient beauty to be found in all things impermanent”. Alone, natural patterns are merely pretty, but in understanding their context as transient items that highlight our own awareness of impermanence and death, they become profound. “You have different feelings when you’re young – everything new is good, but you start to see history develop like a story. After you’ve grown up, you see so many stories, from your family to nature: everything growing and dying and you understand the concept more than you did as a child.”

“You have different feelings when you’re young – everything new is good, but you start to see history develop like a story. After you’ve grown up, you see so many stories, from your family to nature: everything growing and dying and you understand the concept more than you did as a child.”