Consciousness permeates reality. Rather than being just a unique feature of human subjective experience, it’s the foundation of the universe, present in every particle and all physical matter.

Consciousness permeates reality. Rather than being just a unique feature of human subjective experience, it’s the foundation of the universe, present in every particle and all physical matter.

This sounds like easily-dismissible bunkum, but as traditional attempts to explain consciousness continue to fail, the “panpsychist” view is increasingly being taken seriously by credible philosophers, neuroscientists, and physicists, including figures such as neuroscientist Christof Koch and physicist Roger Penrose.

“Why should we think common sense is a good guide to what the universe is like?” says Philip Goff, a philosophy professor at Central European University in Budapest, Hungary. “Einstein tells us weird things about the nature of time that counters common sense; quantum mechanics runs counter to common sense. Our intuitive reaction isn’t necessarily a good guide to the nature of reality.”

David Chalmers, a philosophy of mind professor at New York University, laid out the “hard problem of consciousness” in 1995, demonstrating that there was still no answer to the question of what causes consciousness. Traditionally, two dominant perspectives, materialism and dualism, have provided a framework for solving this problem. Both lead to seemingly intractable complications.

The materialist viewpoint states that consciousness is derived entirely from physical matter. It’s unclear, though, exactly how this could work. “It’s very hard to get consciousness out of non-consciousness,” says Chalmers. “Physics is just structure. It can explain biology, but there’s a gap: Consciousness.” Dualism holds that consciousness is separate and distinct from physical matter—but that then raises the question of how consciousness interacts and has an effect on the physical world.

Panpsychism offers an attractive alternative solution: Consciousness is a fundamental feature of physical matter; every single particle in existence has an “unimaginably simple” form of consciousness, says Goff. These particles then come together to form more complex forms of consciousness, such as humans’ subjective experiences. This isn’t meant to imply that particles have a coherent worldview or actively think, merely that there’s some inherent subjective experience of consciousness in even the tiniest particle.

Panpsychism doesn’t necessarily imply that every inanimate object is conscious. “Panpsychists usually don’t take tables and other artifacts to be conscious as a whole,” writes Hedda Hassel Mørch, a philosophy researcher at New York University’s Center for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness, in an email. “Rather, the table could be understood as a collection of particles that each have their own very simple form of consciousness.”

But, then again, panpsychism could very well imply that conscious tables exist: One interpretation of the theory holds that “any system is conscious,” says Chalmers. “Rocks will be conscious, spoons will be conscious, the Earth will be conscious. Any kind of aggregation gives you consciousness.”

Interest in panpsychism has grown in part thanks to the increased academic focus on consciousness itself following on from Chalmers’ “hard problem” paper. Philosophers at NYU, home to one of the leading philosophy-of-mind departments, have made panpsychism a feature of serious study. There have been several credible academic books on the subject in recent years, and popular articles taking panpsychism seriously.

Interest in panpsychism has grown in part thanks to the increased academic focus on consciousness itself following on from Chalmers’ “hard problem” paper. Philosophers at NYU, home to one of the leading philosophy-of-mind departments, have made panpsychism a feature of serious study. There have been several credible academic books on the subject in recent years, and popular articles taking panpsychism seriously.

One of the most popular and credible contemporary neuroscience theories on consciousness, Giulio Tononi’s Integrated Information Theory, further lends credence to panpsychism. Tononi argues that something will have a form of “consciousness” if the information contained within the structure is sufficiently “integrated,” or unified, and so the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Because it applies to all structures—not just the human brain—Integrated Information Theory shares the panpsychist view that physical matter has innate conscious experience.

Goff, who has written an academic book on consciousness and is working on another that approaches the subject from a more popular-science perspective, notes that there were credible theories on the subject dating back to the 1920s. Thinkers including philosopher Bertrand Russell and physicist Arthur Eddington made a serious case for panpsychism, but the field lost momentum after World War II, when philosophy became largely focused on analytic philosophical questions of language and logic. Interest picked up again in the 2000s, thanks both to recognition of the “hard problem” and to increased adoption of the structural-realist approach in physics, explains Chalmers. This approach views physics as describing structure, and not the underlying nonstructural elements.

“Physical science tells us a lot less about the nature of matter than we tend to assume,” says Goff. “Eddington”—the English scientist who experimentally confirmed Einstein’s theory of general relativity in the early 20th century—“argued there’s a gap in our picture of the universe. We know what matter does but not what it is. We can put consciousness into this gap.”

In Eddington’s view, Goff writes in an email, it’s “”silly” to suppose that that underlying nature has nothing to do with consciousness and then to wonder where consciousness comes from.” Stephen Hawking has previously asked: “What is it that breathes fire into the equations and makes a universe for them to describe?” Goff adds: “The Russell-Eddington proposal is that it is consciousness that breathes fire into the equations.”

The biggest problem caused by panpsychism is known as the “combination problem”: Precisely how do small particles of consciousness collectively form more complex consciousness? Consciousness may exist in all particles, but that doesn’t answer the question of how these tiny fragments of physical consciousness come together to create the more complex experience of human consciousness.

Any theory that attempts to answer that question, would effectively determine which complex systems—from inanimate objects to plants to ants—count as conscious.

An alternative panpsychist perspective holds that, rather than individual particles holding consciousness and coming together, the universe as a whole is conscious. This, says Goff, isn’t the same as believing the universe is a unified divine being; it’s more like seeing it as a “cosmic mess.” Nevertheless, it does reflect a perspective that the world is a top-down creation, where every individual thing is derived from the universe, rather than a bottom-up version where objects are built from the smallest particles. Goff believes quantum entanglement—the finding that certain particles behave as a single unified system even when they’re separated by such immense distances there can’t be a causal signal between them—suggests the universe functions as a fundamental whole rather than a collection of discrete parts.

Such theories sound incredible, and perhaps they are. But then again, so is every other possible theory that explains consciousness. “The more I think about [any theory], the less plausible it becomes,” says Chalmers. “One starts as a materialist, then turns into a dualist, then a panpsychist, then an idealist,” he adds, echoing his paper on the subject. Idealism holds that physical matter does not exist at all and conscious experience is the only thing there is. From that perspective, panpsychism is quite moderate.

Chalmers quotes his colleague, the philosopher John Perry, who says: “If you think about consciousness long enough, you either become a panpsychist or you go into administration.”

Original article here

The sky was a classic California cloudless blue. The light, February soft. The sea breeze, easy, fragrant, and chilly. The waves, mellow laps against the rocky arch at the Natural Bridges State Marine Reserve, about 75 miles south of San Francisco.

The sky was a classic California cloudless blue. The light, February soft. The sea breeze, easy, fragrant, and chilly. The waves, mellow laps against the rocky arch at the Natural Bridges State Marine Reserve, about 75 miles south of San Francisco. Doing it before school or work would be a beautifully irreverent and rebellious thing to do: to remind yourself that this is our most important work as human beings, rather than something that is done after our jobs or homework or housework are complete, and only then if we are not yet completely weighed down by exhaustion.

Doing it before school or work would be a beautifully irreverent and rebellious thing to do: to remind yourself that this is our most important work as human beings, rather than something that is done after our jobs or homework or housework are complete, and only then if we are not yet completely weighed down by exhaustion. The good life is the simple life. Among philosophical ideas about how we should live, this one is a hardy perennial; from Socrates to Thoreau, from the Buddha to Wendell Berry, thinkers have been peddling it for more than two millennia. And it still has plenty of adherents. Magazines such as Real Simple call out to us from the supermarket checkout; Oprah Winfrey regularly interviews fans of simple living such as Jack Kornfield, a teacher of Buddhist mindfulness; the Slow Movement, which advocates a return to pre-industrial basics, attracts followers across continents.

The good life is the simple life. Among philosophical ideas about how we should live, this one is a hardy perennial; from Socrates to Thoreau, from the Buddha to Wendell Berry, thinkers have been peddling it for more than two millennia. And it still has plenty of adherents. Magazines such as Real Simple call out to us from the supermarket checkout; Oprah Winfrey regularly interviews fans of simple living such as Jack Kornfield, a teacher of Buddhist mindfulness; the Slow Movement, which advocates a return to pre-industrial basics, attracts followers across continents. Somewhat paradoxically, then, the case for living simply was most persuasive when most people had little choice but to live that way. The traditional arguments for simple living in effect rationalise a necessity. But the same arguments have less purchase when the life of frugal simplicity is a choice, one way of living among many. Then the philosophy of frugality becomes a hard sell.

Somewhat paradoxically, then, the case for living simply was most persuasive when most people had little choice but to live that way. The traditional arguments for simple living in effect rationalise a necessity. But the same arguments have less purchase when the life of frugal simplicity is a choice, one way of living among many. Then the philosophy of frugality becomes a hard sell. Ask people what they think they’ll look like in 25 years, and chances are they’ll mention how their parents looked at that age. And while genetics certainly play a part, research shows there’s more to the story. Only about 30% of what we see as aging is inherited, explains John Rowe, M.D., Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health.

Ask people what they think they’ll look like in 25 years, and chances are they’ll mention how their parents looked at that age. And while genetics certainly play a part, research shows there’s more to the story. Only about 30% of what we see as aging is inherited, explains John Rowe, M.D., Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health.

Many people see this as their best decade. During our 30s, we’re likely getting more settled in our careers and families, and according to one study our happiness levels are still actively increasing. This is also when making real lifestyle changes can help stave off long-term issues.

Many people see this as their best decade. During our 30s, we’re likely getting more settled in our careers and families, and according to one study our happiness levels are still actively increasing. This is also when making real lifestyle changes can help stave off long-term issues. Everything seems to come together when you hit your 40s. While your family life and career are likely at a high point, caring for aging parents and planning for the future can make it a stressful time.

Everything seems to come together when you hit your 40s. While your family life and career are likely at a high point, caring for aging parents and planning for the future can make it a stressful time. As your children head off to high school and college, now is when you think about how you would like to spend your time. Whether you focus on a new hobby, a volunteer project, or a career change, this decade is all about starting to concentrate on your own wants and needs.

As your children head off to high school and college, now is when you think about how you would like to spend your time. Whether you focus on a new hobby, a volunteer project, or a career change, this decade is all about starting to concentrate on your own wants and needs. Welcome to a new concept: freedom! Whether it’s thanks to becoming an empty nester, being newly retired, or just shaking off societal expectations, it’s all about you from now on. Here’s to prioritizing your mental and physical well-being!

Welcome to a new concept: freedom! Whether it’s thanks to becoming an empty nester, being newly retired, or just shaking off societal expectations, it’s all about you from now on. Here’s to prioritizing your mental and physical well-being! As luck would have it, the puppy and his person are exiting the ballfield just as I am (very slowly) walking by the gate.

As luck would have it, the puppy and his person are exiting the ballfield just as I am (very slowly) walking by the gate. “You remember me?” I exclaim, moving in closer so Tree and I can be heart-to-heart. “How do you do it?” I ask. “How do you stand everything that’s going on?”

“You remember me?” I exclaim, moving in closer so Tree and I can be heart-to-heart. “How do you do it?” I ask. “How do you stand everything that’s going on?” And then another. And another. And another. Soon, I have a whole big pile of weed-parts.

And then another. And another. And another. Soon, I have a whole big pile of weed-parts. “Can I say hello to your puppies?” I ask, crouching down to doggie-reception level. Before either their mom or dad can say yes, I’m ready to receive sloppy kisses.

“Can I say hello to your puppies?” I ask, crouching down to doggie-reception level. Before either their mom or dad can say yes, I’m ready to receive sloppy kisses.

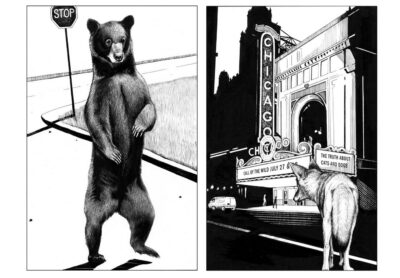

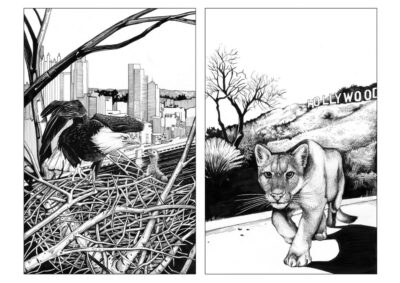

These domesticated animals then get cleared out by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading to this period from about 1920 to 1950 where there are fewer wild animals living in urban areas, particularly in North America, than really at any time before or since. This is a period in which some of the greatest thinkers about urban life were doing their writing, and almost everybody assumed that cities weren’t going to have animals in them.

These domesticated animals then get cleared out by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading to this period from about 1920 to 1950 where there are fewer wild animals living in urban areas, particularly in North America, than really at any time before or since. This is a period in which some of the greatest thinkers about urban life were doing their writing, and almost everybody assumed that cities weren’t going to have animals in them. But these examples are exceptions, not the rule. And this is very time-dependent: Although there are a small number of creatures that can adapt very quickly, for most others, this would take a long period of time — much longer than it takes for their populations to go extinct. And so the problem is [talking] about this as a solution to the fact that we’re rearranging and degrading ecosystems in ways that make the world a much harder place to live for the vast majority of species out there.

But these examples are exceptions, not the rule. And this is very time-dependent: Although there are a small number of creatures that can adapt very quickly, for most others, this would take a long period of time — much longer than it takes for their populations to go extinct. And so the problem is [talking] about this as a solution to the fact that we’re rearranging and degrading ecosystems in ways that make the world a much harder place to live for the vast majority of species out there.

I’m a self-taught artist from Finland, working in many different traditional mediums and digital art. I especially like to create digital art that feels as if it’s made in a traditional medium.

I’m a self-taught artist from Finland, working in many different traditional mediums and digital art. I especially like to create digital art that feels as if it’s made in a traditional medium.

The great likelihood is that you’re going to be adapting to the conditions you already have. Those conditions might not appear to be “optimal” in the traditional horticultural sense. But plants grow in the wild without fertilizer. Survivors adapt, learning to love even marginal soil. They also forge relationships with other plants, animals, and the microbiology of the soil. These relationships become the foundation of a sustainable and resilient landscape.

The great likelihood is that you’re going to be adapting to the conditions you already have. Those conditions might not appear to be “optimal” in the traditional horticultural sense. But plants grow in the wild without fertilizer. Survivors adapt, learning to love even marginal soil. They also forge relationships with other plants, animals, and the microbiology of the soil. These relationships become the foundation of a sustainable and resilient landscape. Now that you’ve observed, ask…What plants will thrive in my yard? In other words, what does nature want? And what do I want? Where these desires meet will be the foundation of your design.

Now that you’ve observed, ask…What plants will thrive in my yard? In other words, what does nature want? And what do I want? Where these desires meet will be the foundation of your design.

Watch how the landscape evolves. “Don’t be discouraged if some of the plants in your palette don’t do well, even though you did the research,” says Max Kanter, cofounder of Saturate, an ecologically minded gardening company in Los Angeles. Some might not be placed quite right, while others will thrive in ways you didn’t expect. “Start to practice the idea that the garden is a process,” he says. It’s not an installation or a transaction; it’s a relationship.

Watch how the landscape evolves. “Don’t be discouraged if some of the plants in your palette don’t do well, even though you did the research,” says Max Kanter, cofounder of Saturate, an ecologically minded gardening company in Los Angeles. Some might not be placed quite right, while others will thrive in ways you didn’t expect. “Start to practice the idea that the garden is a process,” he says. It’s not an installation or a transaction; it’s a relationship.