Remember the last time someone flipped you the bird? Whether or not that single finger was accompanied by spoken obscenities, you knew exactly what it meant.

The conversion from movement into meaning is both seamless and direct, because we are endowed with the capacity to speak without talking and comprehend without hearing. We can direct attention by pointing, enhance narrative by miming, emphasize with rhythmic strokes and convey entire responses with a simple combination of fingers.

The tendency to supplement communication with motion is universal, though the nuances of delivery vary slightly. In Papua New Guinea, for instance, people point with their noses and heads, while in Laos they sometimes use their lips. In Ghana, left-handed pointing can be taboo, while in Greece or Turkey forming a ring with your index finger and thumb to indicate everything is A-OK could get you in trouble.

Despite their variety, gestures can be loosely defined as movements used to reiterate or emphasize a message — whether that message is explicitly spoken or not. A gesture is a movement that “represents action,” but it can also convey abstract or metaphorical information. It is a tool we carry from a very young age, if not from birth; even children who are congenitally blind naturally gesture to some degree during speech. Everybody does it. And yet, few of us have stopped to give much thought to gesturing as a phenomenon — the neurobiology of it, its development, and its role in helping us understand others’ actions. As researchers delve further into our neural wiring, it’s becoming increasingly clear that gestures guide our perceptions just as perceptions guide our actions.

An Innate Tendency to Gesture

Susan Goldin-Meadow is considered a titan in the gesture field — although, as she says, when she first became interested in gestures during the 1970s, “there wasn’t a field at all.” A handful of others had worked on gestures but almost entirely as an offshoot of nonverbal-behavior research. She has since built her career studying the role of gesture in learning and language creation, including the gesture system that deaf children create when they are not exposed to sign language. (Sign language is distinct from gesturing because it constitutes a fully developed linguistic system.) At the University of Chicago, where she is a professor, she runs one of the most prominent labs investigating gesture production and perception.

“It’s a wonderful window into unspoken thoughts, and unspoken thoughts are often some of the most interesting,” she said, with plenty of gestures of her own.

Many researchers who trained with Goldin-Meadow are now pursuing similar questions outside the University of Chicago. Miriam Novack completed her doctorate under Goldin-Meadow in 2016, and as a postdoc at Northwestern University she examines how gesture develops over the course of a lifetime.

No other species points, Novack explained, not even chimpanzees or apes, according to most reports, unless they are raised by people. Human babies, in contrast, often point before they can speak, and our ability to generate and understand symbolic motions continues to evolve in tandem with language. Gesture is also a valuable tool in the classroom, where it can help young children generalize verbs to new contexts or solve math equations. “But,” she said, “it’s not necessarily clear when kids begin to understand that our hand movements are communicative — that they’re part of the message.”

When children can’t find the words to express themselves, they let their hands do the talking. Novack, who has studied infants as young as 18 months, has seen how the capacity to derive meaning from movement increases with age. Adults do it so naturally, it’s easy to forget that mapping meaning onto hand shape and trajectory is no small feat.

Gestures may be simple actions, but they don’t function in isolation. Research shows that gesture not only augments language, but also aids in its acquisition. In fact, the two may share some of the same neural systems. Acquiring gesture experience over the course of a lifetime may also help us intuit meaning from others’ motions. But whether individual cells or entire neural networks mediate our ability to decipher others’ actions is still up for debate.

Embodied Cognition

Inspired by the work of Noam Chomsky, a towering figure in linguistics and cognitive science, some researchers have long maintained that language and sensorimotor systems are distinct entities — modules that need not work together in gestural communication, even if they are both means of conveying and interpreting symbolic thought. Because researchers don’t yet fully understand how language is organized within the brain or which neural circuits derive meaning from gesture, the question is unsettled. But many scientists, like Anthony Dick, an associate professor at Florida International University, theorize that the two functions rely on some of the same brain structures.

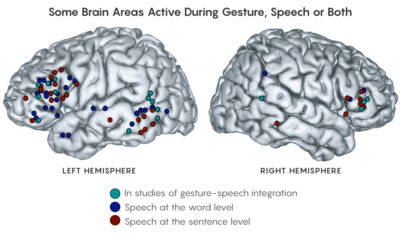

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans of brain activity, Dick and colleagues have demonstrated that the interpretation of “co-speech” gestures consistently recruits language processing centers. The specific areas involved and the degree of activation vary with age, which suggests that the young brain is still honing its gesture-speech integration skills and refining connections between regions. In Dick’s words, “Gesture essentially is one spire in a broader language system,” one that integrates both semantic processing regions and sensorimotor areas. But to what extent is the perception of language itself a sensorimotor experience, a way of learning about the world that depends on both sensory impressions and movements?

Manuela Macedonia had only recently finished her master’s degree in linguistics when she noticed a recurring pattern among the students to whom she was teaching Italian at Johannes Kepler University Linz (JKU): No matter how many times they repeated the same words, they still couldn’t stammer out a coherent sentence. Printing phrases ad nauseam didn’t do much to help, either. “They became very good listeners,” she said, “but they were not able to speak.”

She was teaching by the book: She had students listen, write, practice and repeat, yet it wasn’t enough. Something was missing.

Today, as a senior scientist at the Institute of Information Engineering at JKU and a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Macedonia is getting closer to a hypothesis that sounds a lot like Dick’s: that language is anything but modular.

When children are learning their first language, Macedonia argues, they absorb information with their entire bodies. A word like “onion,” for example, is tightly linked to all five senses: Onions have a bulbous shape, papery skin that rustles, a bitter tang and a tear-inducing odor when sliced. Even abstract concepts like “delight” have multisensory components, such as smiles, laughter and jumping for joy. To some extent, cognition is “embodied” — the brain’s activity can be modified by the body’s actions and experiences, and vice versa. It’s no wonder, then, that foreign words don’t stick if students are only listening, writing, practicing and repeating, because those verbal experiences are stripped of their sensory associations.

Macedonia has found that learners who reinforce new words by performing semantically related gestures engage their motor regions and improve recall. Don’t simply repeat the word “bridge”: Make an arch with your hands as you recite it. Pick up that suitcase, strum that guitar! Doing so wires the brain for retention, because words are labels for clusters of experiences acquired over a lifetime.

Multisensory learning allows words like “onion” to live in more than one place in the brain — they become distributed across entire networks. If one node decays due to neglect, another active node can restore it because they’re all connected. “Every node knows what the other nodes know,” Macedonia said.

Wired by Experience

The power of gestures to enrich speech may represent only one way in which gesture is integrated with sensory experiences. A growing body of work suggests that, just as language and gesture are intimately entwined, so too are motor production and perception. Specifically, the neural systems underlying gesture observation and understanding are influenced by our past experiences of generating those same movements, according to Elizabeth Wakefield.

Wakefield, another Goldin-Meadow protégé, directs her own lab as an assistant professor at Loyola University Chicago, where she studies the way everyday actions aid learning and influence cognition. But before she could examine these questions in depth, she needed to understand how gesture processing develops. As a graduate student working with the neuroscientist Karin James at Indiana University in 2013, she performed an fMRI study that was one of the first to examine gesture perception in both children and adults.

When the participants watched videos of an actress who gestured as she spoke, their visual and language processing regions weren’t the only areas firing. Brain areas associated with motor experiences were active as well, even though the participants lay still in the scanner. Adults showed more activity in these regions than children did, however, and Wakefield thinks that is because the adults had more experience with making similar motions (children tend to gesture less when they talk).

“We, to my knowledge, were the first people looking at gesture processing across development,” Wakefield said. “That small body of literature on how gesture is processed developmentally has important implications for how we might think about gesture shaping learning.”

Wakefield’s study is not the only evidence that gesture perception and purposeful action both stand on the same neural foundation. Countless experiments have demonstrated a similar motor “mirroring” phenomenon for actions associated with ballet, basketball, playing the guitar, tying knots and even reading music. In each case, when skilled individuals observed their craft being performed by others, their sensorimotor areas were more active than the corresponding areas in participants with less expertise.

(Paradoxically, some experiments observed exactly the opposite effect: Experts’ brains reacted less than those of non-experts when they watched someone with their skills. But researchers theorized that in those cases, experience had made their brains more efficient at processing the motions.)

Lorna Quandt, an assistant professor at Gallaudet University who studies these phenomena among the deaf and hard of hearing, takes a fine-grained approach. She breaks gestures down into their sensorimotor components, using electroencephalography (EEG) to show that memories of making certain actions change how we predict and perceive others’ gestures.

In one study, she and her colleagues recorded the EEG patterns of adult participants while they handled objects of varying colors and weights, and then while they watched a man in a video interact with the same items. Even when the man simply mimed actions around the objects or pointed to them without making contact, the participants’ brains reacted as though they were manipulating the articles themselves. Moreover, their neural activity reflected their own experience: The EEG patterns showed that their recollections of whether the objects were heavy or light predictably influenced their perception of what the man was doing.

“When I see you performing a gesture, I’m not just processing what I’m seeing you doing; I’m processing what I think you’re going to do next,” Quandt said. “And that’s a really powerful lens through which to view action perception.” My brain anticipates your sensorimotor experiences, if only by milliseconds.

Exactly how much motor experience is required? According to Quandt’s experiments, for the straightforward task of becoming more expert at color-weight associations, just one tactile trial is enough, although reading written information is not.

According to Dick, the notion that brain motor areas are active even when humans are immobile but observing others’ movements (a phenomenon known as “observation-execution matching”) is generally well-established. What remains controversial is the degree to which these same regions extract meaning from others’ actions. Still more contentious is what mechanism would serve as the basis for heightened understanding through sensorimotor activation. Is it coordinated activity across multiple brain regions, or could it all boil down to the activity of individual cells?

Mirror Neurons or Networks?

More than a century ago, the psychologist Walter Pillsbury wrote: “There is nothing in the mind that has not been explained in terms of movement.” This concept has its modern incarnation in the mirror neuron theory, which posits that the ability to glean meaning from gesture and speech can be explained by the activation of single cells in key brain regions. It’s becoming increasingly clear, however, that the available evidence regarding the role of mirror neurons in everyday behaviors may have been oversold and overinterpreted.

The mirror neuron theory got its start in the 1990s, when a group of researchers studying monkeys found that specific neurons in the inferior premotor cortex responded when the animals made certain goal-directed movements like grasping. The scientists were surprised to note that the same cells also fired when the monkeys passively observed an experimenter making similar motions. It seemed like a clear case of observation-execution matching but at the single-cell level.

The researchers came up with a few possible explanations: Perhaps these “mirror neurons” were simply communicating information about the action to help the monkey select an appropriate motor response. For instance, if I thrust my hand toward you to initiate a handshake, your natural reaction is probably to mirror me and do the same.

The actions of others are perceived through the lens of the self.

Alternatively, these single cells could form the basis for “action understanding,” the way we interpret meaning in someone else’s movements. That possibility might allow monkeys to match their own actions to what they observed with relatively little mental computation. This idea ultimately usurped the other because it was such a beautifully simple way to explain how we intuit meaning from others’ movements.

As the years passed, evidence poured in for a similar mechanism in humans, and mirror neurons became implicated in a long list of phenomena, including empathy, imitation, altruism and autism spectrum disorder, among others. And after reports of mirroring activity in related brain regions during gesture observation and speech perception, mirror neurons became associated with language and gesture, too.

Gregory Hickok, a professor of cognitive and language sciences at the University of California, Irvine, and a staunch mirror neuron critic, maintains that, decades ago, the founders of mirror neuron theory threw their weight behind the wrong explanation. In his view, mirror neurons deserve to be thoroughly investigated, but the pinpoint focus on their roles in speech and action understanding has hindered research progress. Observation-execution matching is more likely to be involved in motor planning than in understanding, he argues.

Even those who continue to champion the theory of action understanding have begun to pump the brakes, according to Valeria Gazzola, who leads the Social Brain Laboratory at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience and is an associate professor at the University of Amsterdam. Although she is an advocate of the mirror neuron theory, Gazzola acknowledged that there’s no consensus about what it actually means to “understand” an action. “There is still some variability and misunderstanding,” she said. While mirror neurons serve as an important component of cognition, “whether they explain the whole story, I would say that’s probably not true.”

It’s a wonderful window into unspoken thoughts, and unspoken thoughts are often some of the most interesting.

Initially, most evidence for mirroring in humans was derived from studies that probed the activity of millions of neurons simultaneously, using techniques such as fMRI, EEG, magnetoencephalography and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Researchers have since begun to experiment with techniques like fMRI adaptation, which they can use to analyze subpopulations of cells in specific cortical regions. But they only rarely have the opportunity to take direct measurements from individual cells in the human brain, which would provide the most direct proof of mirror neuron activity.

“I have no doubt that mirror neurons exist,” Hickok said, “but all of those brain imaging and brain activation studies are correlational. They do not tell you anything about causation.”

Moreover, people who cannot move or speak because of motor disabilities like severe forms of cerebral palsy can in most cases still perceive speech and gestures. They don’t need fully functioning motor systems (and mirror neurons) to perform tasks that require action understanding as it’s loosely defined. Even in monkeys, Hickok said, there is no evidence that damage to mirror neurons produces deficits in action observation.

Because claims about individual cells remain so difficult to corroborate empirically, most investigators today choose their words carefully. Monkeys may have “mirror neurons,” but humans have “mirroring systems,” “neural mirroring” or an “action-observation network.” (According to Hickok, even the monkey research has shifted more toward a focus on mirroring effects in networks and systems.)

Quandt, who considers herself a mirror neuron centrist, makes no claims about how different experiences change the function of individual cells based on her EEG experiments. That said, she is “completely convinced” that parts of the human sensorimotor system are involved in parsing and processing other people’s gestures. “I am 100 percent sure that’s true,” she said. “It would take a lot to convince me otherwise.”

Researchers may not be able to pinpoint the exact cells that help us to communicate and learn with our bodies, but the overlap between multisensory systems is undeniable. Gesture allows us to express ourselves, and it also shapes the way we understand and interpret others. To quote one of Quandt’s papers: “The actions of others are perceived through the lens of the self.”

So, the next time someone gives you the one-finger salute, take a moment to appreciate what it takes to receive that message loud and clear. If nothing else, it might lessen the sting a bit.

Original article here

The electrons are essentially drawn across the cytochrome oxidase system by the oxygen at the positive pole of the intracellular battery. The more oxygen in the system, the stronger the pull. Breathing exercises, eating high-oxygen foods, and living in atmospherically clean, high-oxygen environments increases our overall oxygen content. The cytochrome oxidase system exists in every cell and requires electron energy to function. This electron energy comes from plant foods as well as what we directly absorb. When the food is cooked, the basic harmonic resonance pattern of the living electron energy of the live food is at least partially destroyed. Once understanding this scientific evidence, the logical step is to eat high-electron foods such as fruits, vegetables, raw nuts and seeds, and sprouted or soaked grains. People who eat refined, cooked, highly processed foods diminish the amount of solar electrons energizing the system.

The electrons are essentially drawn across the cytochrome oxidase system by the oxygen at the positive pole of the intracellular battery. The more oxygen in the system, the stronger the pull. Breathing exercises, eating high-oxygen foods, and living in atmospherically clean, high-oxygen environments increases our overall oxygen content. The cytochrome oxidase system exists in every cell and requires electron energy to function. This electron energy comes from plant foods as well as what we directly absorb. When the food is cooked, the basic harmonic resonance pattern of the living electron energy of the live food is at least partially destroyed. Once understanding this scientific evidence, the logical step is to eat high-electron foods such as fruits, vegetables, raw nuts and seeds, and sprouted or soaked grains. People who eat refined, cooked, highly processed foods diminish the amount of solar electrons energizing the system.

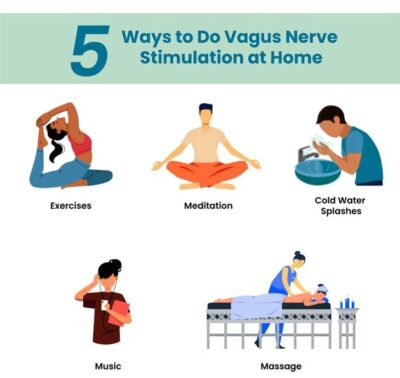

Singing, humming, chanting and even gargling can improve vagal tone because the vagus nerve controls your vocal cords and the muscles at the back of your throat, explains Dr Ravindran. A brain imaging study even found that the humming involved in the meditation chant ‘om’ reduced activity in areas of the brain associated with depression.

Singing, humming, chanting and even gargling can improve vagal tone because the vagus nerve controls your vocal cords and the muscles at the back of your throat, explains Dr Ravindran. A brain imaging study even found that the humming involved in the meditation chant ‘om’ reduced activity in areas of the brain associated with depression. Everyone has a few comforting quirks that they only indulge in behind closed doors. For some, it’s lying on the floor to relax. For others, it’s talking to themselves out loud. These unhinged habits might seem embarrassing, especially if you get caught in the act, but then you go on social media and realize there are dozens — and sometimes even hundreds of thousands — of other people just like you.

Everyone has a few comforting quirks that they only indulge in behind closed doors. For some, it’s lying on the floor to relax. For others, it’s talking to themselves out loud. These unhinged habits might seem embarrassing, especially if you get caught in the act, but then you go on social media and realize there are dozens — and sometimes even hundreds of thousands — of other people just like you.

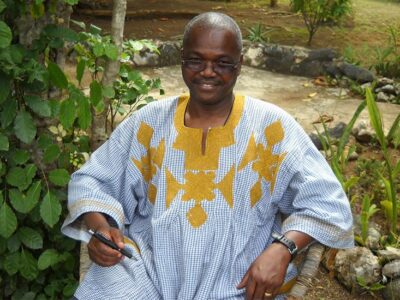

Malidoma is from a collectivist society. Born into the Dagara tribe in Burkina Faso, he is the grandson of a renowned healer, who travels around the world but is based in the U.S. Malidoma sees himself as a bridge between his culture and the United States, existing to “bring the wisdom of our people to this part of the world.” Malidoma’s “career”—he chuckles at the term—is some combination of cultural ambassador, homeopath, and sage. He travels the country doing rituals and consultations, writing books, and giving speeches. He has three master’s degrees and two doctorates from Brandeis University. Sometimes he calls himself a “shaman,” because people know what that means (sort of) and it’s similar to his title back in Burkina Faso—a titiyulo, one who “constantly inquires with other dimensions.”

Malidoma is from a collectivist society. Born into the Dagara tribe in Burkina Faso, he is the grandson of a renowned healer, who travels around the world but is based in the U.S. Malidoma sees himself as a bridge between his culture and the United States, existing to “bring the wisdom of our people to this part of the world.” Malidoma’s “career”—he chuckles at the term—is some combination of cultural ambassador, homeopath, and sage. He travels the country doing rituals and consultations, writing books, and giving speeches. He has three master’s degrees and two doctorates from Brandeis University. Sometimes he calls himself a “shaman,” because people know what that means (sort of) and it’s similar to his title back in Burkina Faso—a titiyulo, one who “constantly inquires with other dimensions.”

I had grown up a good Sikh boy: I wore a turban, didn’t cut my hair, didn’t drink or smoke. The idea of a god that acted in the world had long seemed implausible, yet it wasn’t until I started studying evolution in earnest that the strictures of religion and of everyday conventions began to feel brittle. By my junior year of college, I thought of myself as a materialist, open-minded but skeptical of anything that smacked of the supernatural. Celebrationism came soon after. It expanded from an ethical road map into a life philosophy, spanning aesthetics, spirituality, and purpose. By the end of my senior year, I was painting my fingernails, drawing swirling mehndi tattoos on my limbs, and regularly walking without shoes, including during my college graduation. “Why, Manvir?” my mother asked, quietly, and I launched into a riff about the illusory nature of normativity and about how I was merely a fancy organism produced by cosmic mega-forces.

I had grown up a good Sikh boy: I wore a turban, didn’t cut my hair, didn’t drink or smoke. The idea of a god that acted in the world had long seemed implausible, yet it wasn’t until I started studying evolution in earnest that the strictures of religion and of everyday conventions began to feel brittle. By my junior year of college, I thought of myself as a materialist, open-minded but skeptical of anything that smacked of the supernatural. Celebrationism came soon after. It expanded from an ethical road map into a life philosophy, spanning aesthetics, spirituality, and purpose. By the end of my senior year, I was painting my fingernails, drawing swirling mehndi tattoos on my limbs, and regularly walking without shoes, including during my college graduation. “Why, Manvir?” my mother asked, quietly, and I launched into a riff about the illusory nature of normativity and about how I was merely a fancy organism produced by cosmic mega-forces.