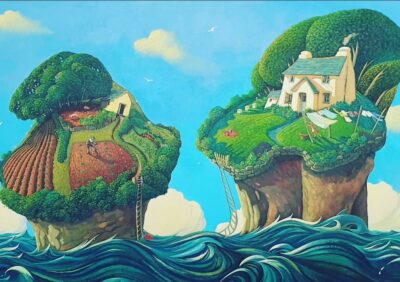

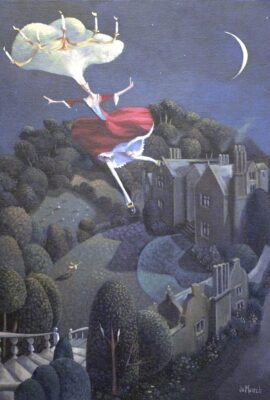

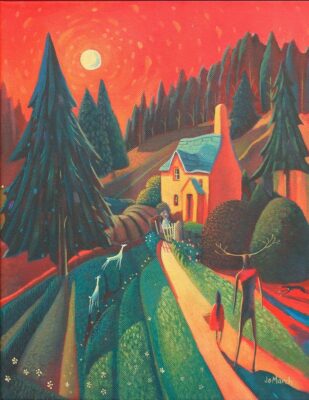

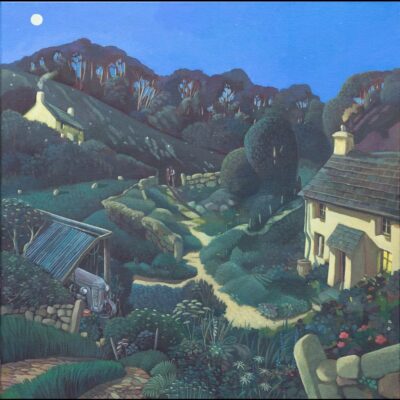

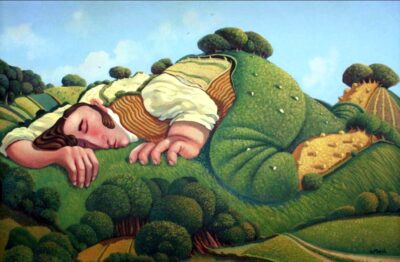

What is consciousness, and who (or what) is conscious — humans, nonhumans, nonliving beings? Which varieties of consciousness do we recognize? In their book “Picturing the Mind,” Simona Ginsburg and Eva Jablonka, two leading voices in evolutionary consciousness science, pursue these and other questions through a series of “vistas” — over 65 brief, engaging texts, presenting some of the views of poets, philosophers, psychologists, and biologists, accompanied by Anna Zeligowski’s lively illustrations.

Each picture and text serves as a starting point for discussion. In the texts that follow, excerpted from the vista “How Did Consciousness Evolve?” the authors offer a primer on evolutionary theory, consider our evolutionary transition from nonsentient to sentient organisms, explore the torturous relation between learning studies and consciousness research, and ponder the origins and evolution of suffering and the imagination.

Evolutionary Theory

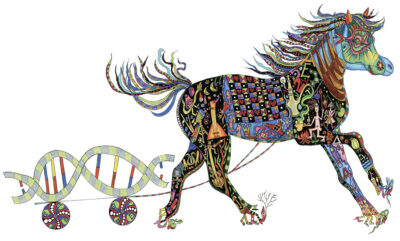

Evolutionary theory is a deceptively simple theory, which is why many people who have only a cursory acquaintance with it are nevertheless convinced that they fully understand it. Its basic assumptions are indeed simple. The first assumption, which was systematically explored first by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and then by Charles Darwin, is that there was a single ancestor, or very few ancestors, of all living organisms. This is the principle of Descent with modification: all organisms are descended, with modifications, from ancestors that lived long ago.

The second principle, which is central to Darwin’s theory, is the principle of Natural selection: organisms with hereditary variations that render them better adapted to their local environment than others in their population leave behind more offspring. Darwin showed that this simple process, when applied recursively, can account for the evolution of complex organs like the eye, and, with the addition of some plausible auxiliary hypotheses, can explain the diversity of living species and their geographic distribution. In the last paragraph of “The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection,” Darwin summarized his ideas:

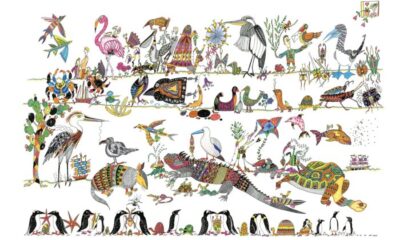

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with reproduction; Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of less- improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Once he put forward his ideas, various scientists tried to crystallize and summarize Darwin’s view. For example, in the twentieth century, John Maynard Smith suggested that four basic processes underlie evolution by natural selection:

(i) Multiplication: an entity gives rise to two or more others.

(ii) Variation: not all entities are identical.

(iii) Heredity: like usually begets like. Variant X usually begets offspring X, but infrequently begets offspring Y.

(iv) Competition: some heritable variations affect the success of entities in persisting and multiplying more than others.

Although it sounds simple, when we unpack these processes, we appreciate how complex evolutionary theory actually is. There are multiple ways in which reproduction occurs and there are different types of inherited variations. Maynard Smith, like most 20th-century biologists, focused on DNA- based genetic variability, but since the early 2000s, the idea that variations in DNA drive all evolutionary change has been abandoned; it is now recognized that heritable variations in DNA, in patterns of gene expression, in behavior, and in culture are all important. Variation in these hereditary units can arise randomly or can be partially directed because heredity and development can be coupled. For example, stressful conditions during development can induce changes in gene expression that can be transmitted to the next generation. It has also been accepted that there are multiple targets and levels of selection within individuals, between individuals and between lineages, and that organisms have fuzzy boundaries. (Are the symbiotic bacteria in your gut part of you?) Crucially, organisms are not passive subjects of natural selection — they actively construct the environment in which they are selected and bequeath these ecological legacies to their offspring.

As evolutionary biologist Mary Jane West-Eberhard put it: “Genes are followers, not leaders, in evolution.”

How, then, should evolutionary analysis proceed? We could start by tracing evolutionary change at the molecular-genetic, physiological-developmental, behavioral, or cultural levels. However, since organisms adjust to changing conditions in the external world and in their own genome by altering their behavior and physiology, cultural and behavioral adaptations frequently precede genetic changes and shape the conditions in which variations are selected. Genetic changes that stabilize or fine-tune the behavioral or developmental changes follow. As evolutionary biologist Mary Jane West-Eberhard put it: “Genes are followers, not leaders, in evolution.”

In the 21st century, this integrative approach to evolutionary reasoning, which incorporates the effects of variations in DNA, development, behavior, and culture is being embraced by a growing number of biologists, including us.

Evolutionary Transitions

How should we think about the evolutionary transition from non-sentient to sentient organisms? There are several useful ways of carving up the living world and thinking about evolutionary transitions between forms and ways of life. Ecologists distinguish between modes of living such as terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial modes, and study the transitions from water to land or from land to air. In contrast, evolutionary biologists John Maynard Smith and Eörs Szathmáry have described major evolutionary transitions in terms of qualitative changes in the way information is stored, processed, and transmitted. Examples of such transitions include the transition from single cells to multicellular organisms, and the transition from nonlinguistic communication to communication through symbolic language.

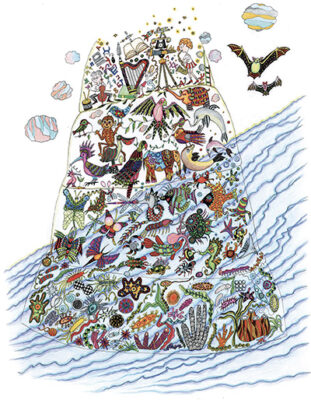

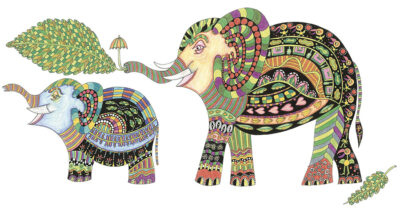

The philosopher Daniel Dennett suggests another way of thinking about broad patterns of life. He distinguishes four progressively sophisticated, hierarchically nested types of selection, which underlie what he calls a “generate-and- test- tower.” Organisms such as bacteria, sponges, and plants, which can adapt evolutionarily through natural selection, dwell on the first floor; the second floor is inhabited by organisms such as snails, fish, and mice, which, in addition to selection during evolutionary history, learn through trial-and-error and selective reinforcement during their lifetime. Organisms that can also select among imagined actions and scenarios, like elephants, dolphins, and great apes, live on the third floor, while human beings, with the extra capacity to select among symbolically represented possibilities and who are subject to cultural selection, live on the fourth.

None of these classifications explicitly mentions sentience. Sentience is, however, central to the view of Aristotle, which we described in the first vista. Aristotle distinguished between three goal-directed and hierarchically nested types of “soul,” or modes of living organization: the “nutritive-reproductive” soul of non-sentient organisms like plants, the goals of which are survival and reproduction; the “sensitive” soul of sentient organisms, whose goals are the fulfillment of desires and appetites; and the “rational” soul of humans, whose goal is to satisfy abstract symbolic values such as justice and beauty. In our book “The Evolution of the Sensitive Soul,” we reframed Aristotle’s hierarchy within the framework of evolutionary theory, and offered a unifying scheme for explaining the evolutionary transitions to life, sentience, and reflectivity.

An Evolutionary-Transition Approach to Consciousness

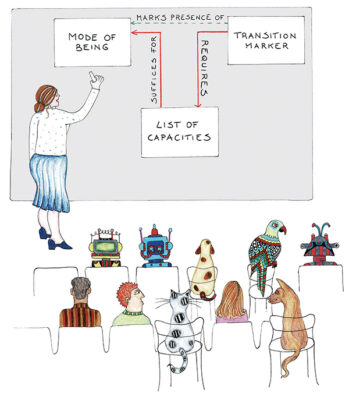

How can we develop an evolutionary theory of consciousness when there is so much disagreement over what consciousness is and which organisms are conscious? Our way of approaching this question takes as its inspiration the way the Hungarian chemist Tibor Gánti tackled a similar problem, the problem of how life (another elusive notion) originated. Gánti started by compiling a list of capacities that, in spite of the different views about the nature of life, are generally deemed jointly sufficient for the simplest, “minimal” life. He then built a theoretical model of a minimal living system that implements all these capacities.

Following Gánti’s methodology, our first task is to identify a list of capacities that, when all are present, most consciousness researchers would regard as sufficient for an organism to be deemed minimally conscious. Such an organism would be able to perceive, feel, and think, from its own private point of view.

A consensus list of consciousness capacities is a step forward, but identifying each and every capacity may be difficult, and a list does not tell us how they interact to form a conscious being. If we could find a single system-property — an evolutionary marker of consciousness — that indicates that the organism has evolved all the capacities in the consensus list, we would be in a much better position. Finding such a single, diagnostic transition marker would make it possible to identify the simplest evolved conscious being, reconstruct the processes and structures that underlie it, and figure out how they interact. If we can follow the evolution of the marker and therefore the evolution of consciousness, we can discover when and how the conscious mode of being originated.

A consensus list of consciousness capacities is a step forward, but identifying each and every capacity may be difficult, and a list does not tell us how they interact to form a conscious being. If we could find a single system-property — an evolutionary marker of consciousness — that indicates that the organism has evolved all the capacities in the consensus list, we would be in a much better position. Finding such a single, diagnostic transition marker would make it possible to identify the simplest evolved conscious being, reconstruct the processes and structures that underlie it, and figure out how they interact. If we can follow the evolution of the marker and therefore the evolution of consciousness, we can discover when and how the conscious mode of being originated.

As we will see, evolutionary transition markers to the living, the living conscious, and (tentatively) the living-conscious-rational modes of being (the three Aristotelian “souls”) have been suggested. Each of these evolutionary transition markers entails a consensus list of capacities that are sufficient to allow us to ascribe the corresponding mode of being to an entity.

Learning and Consciousness: An Unlikely Relation?

Is there a single, tangible property that when present in an entity means that all the characteristics of consciousness are in place — an evolutionary transition marker of consciousness? We believe that we have identified such a marker. Our marker is a form of open-ended associative learning, which we call unlimited associative learning (UAL).

Before we describe this marker and argue our case, we must say a few words about learning and about the torturous relation between learning studies and consciousness research in the 20th century.

Learning, an experience-dependent change in behavior, requires (i) that a sensory stimulus leads to a change in the internal state of the system; (ii) that a memory trace of the internal change is stored through a process that involves positive or negative reinforcement; and (iii) that later exposures to the same or a similar stimulus are manifest as changes to the threshold of the behavioral response. Characterizing these processes, the relations between them, and the mechanisms underlying them in living organisms is a complex endeavor. Just as with evolutionary processes, where the nature of reproduction, variation production, and selection have to be qualified, the study of learning requires that we consider the kinds of stimuli that are attended to, the mechanisms of storage and of recall, the relevant rewards and punishments and the ways the organism responds.

Nineteenth-century biologists thought that being able to learn by making new behavioral adjustments or modifying old ones was a criterion of consciousness.

Nineteenth-century biologists thought that being able to learn by making new behavioral adjustments or modifying old ones was a criterion of consciousness. This way of thinking changed dramatically with the advent of behaviorism, a strand of experimental psychology that dominated the English-speaking world from the beginning of the twentieth century until the 1970s. Behaviorists redefined psychology as the study of learned behavior, scornfully objecting to any mention of terms like consciousness or mind. An influential psychology textbook from 1953 explained that notions like “mind” and “ideas” “are being invented on the spot for the sole purpose of providing spurious explanations. . . . Since mental or psychic events are asserted to lack the dimensions of physical science, we have an additional reason for rejecting them” (B. F. Skinner, “Science and Human Behavior”).

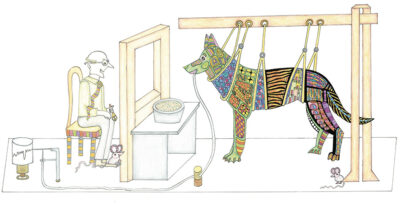

The behaviorists focused on two types of associative learning. In the first, classical or Pavlovian conditioning (named after the physiologist Ivan Pavlov), an animal learns that something it perceives, which is of no relevance to it (a “neutral stimulus” in the behaviorists’ jargon), predicts a stimulus that invariably accompanies a reward or a punishment such as food or pain, to which it reflexively responds. For example, the smell of food that accompanies the reward (food) elicits the salivation reflex in a hungry dog. The sound of a buzzer (or bell), on the other hand, normally does not elicit salivation — it is “neutral” with respect to salivation. However, it will eventually elicit salivation, even when there is no smell of food, if the buzz repeatedly occurs before the smell. Pavlov measured the internal state of the dog by counting the number of drops of saliva at different stages of learning.

In the second type of associative learning, Skinnerian conditioning (named after the psychologist B. F. Skinner), an animal learns what to do in order get a reward or avoid a punishment (known in behaviorist jargon as positive or negative reinforcement). For example, a hungry rat can learn to press a lever in its cage if this action is followed by the delivery of food. In general, actions that are followed by a positive (or negative) outcome will be more (or less) likely to occur in the future, under similar circumstances.

Skinner’s experiments, like those of Pavlov, were conducted in drastically impoverished and artificial conditions, totally different from those in which animals live in the real world. Nevertheless, Skinner suggested that complex behavior, including the “verbal behavior” of humans (this was his term for language comprehension and production), is the result of a sequence of reinforcements.

Skinner’s experiments, like those of Pavlov, were conducted in drastically impoverished and artificial conditions, totally different from those in which animals live in the real world.

The increasing tensions between the obvious limitations and the grandiose pretensions of behaviorism eventually led to its demise. However, the ongoing study of associative learning led to new insights. For example, it was discovered that learning depends on how surprising, how unexpected, the predictive neutral stimulus or action is of the reinforcement. A totally predictable stimulus requires no learning, whereas one that does not match expectations is newsworthy. Learning in animals, on which machine- learning algorithms are patterned, involves the updating and minimization of mismatched expectations.

The study of associative learning today includes the investigation of the underlying cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms in ecologically relevant conditions such as the social conditions in which animals learn from each other. It is a rich and productive research program, which is no longer constrained by the behaviorists’ maxims. There is an irony in our (qualified) return to the 19th-century suggestion that open-ended associative learning is an evolutionary transition marker of consciousness, the very term that behaviorists tried to purge from psychology.

The study of associative learning today includes the investigation of the underlying cognitive and neurobiological mechanisms in ecologically relevant conditions such as the social conditions in which animals learn from each other. It is a rich and productive research program, which is no longer constrained by the behaviorists’ maxims. There is an irony in our (qualified) return to the 19th-century suggestion that open-ended associative learning is an evolutionary transition marker of consciousness, the very term that behaviorists tried to purge from psychology.

Of course I do as I’m told.

Hunger and shock are great reinforcers

Push lever and

Obey the rule

And NEVER

Show my inner soul

~ Jane Monet

Unlimited Associative Learning (UAL) Is the Evolutionary Transition Marker of Consciousness

What is the evolutionary transition marker of minimal consciousness? Following Gánti’s methodology we started by compiling a consensus list of consciousness characteristics based on the work of psychologists, philosophers, and neurobiologists:

- Binding/unification: seeing the apple as a composite whole (red, round, smooth) yet with discernable features

- Global accessibility and broadcast: back and forth interactions among specialized brain modules allowing comparisons, discriminations, generalizations, and evaluations that inform decision-making

- Selective attention and active exclusion: excluding or amplifying signals according to past and present context

- Intentionality (aboutness; representation): the mapping (representations) of body, world, action, and their relations

- Integration through time: Holding on to incoming information long enough for it to be integrated and evaluated, so the present can be said to have duration

- Flexible evaluative system and goals: evaluating perceptions and actions as rewarding or punishing according to context

- Agency and embodiment: inherent spontaneous activity and goal-directed behavior

- A sense of self: registration of self/other and a stable perspective

On the basis of this list, we suggest that the evolutionary transition marker of minimal consciousness, which is the within-lifetime analog of unlimited heredity in evolutionary time, is Unlimited associative learning (UAL). UAL is the within-lifetime analog of unlimited heredity in evolutionary time. An organism with a capacity for UAL can, during its own lifetime, go on learning from experience about the world and about itself in a practically unrestricted way.

(i) It can distinguish between novel complex patterns of stimuli and actions. For example, it can learn to navigate in a new terrain — to discriminate between different types of animals, between different routes leading to food and shelter. The learned patterns are genuinely novel: they are not reflex-eliciting patterns, nor have they been learned in the past.

(i) It can distinguish between novel complex patterns of stimuli and actions. For example, it can learn to navigate in a new terrain — to discriminate between different types of animals, between different routes leading to food and shelter. The learned patterns are genuinely novel: they are not reflex-eliciting patterns, nor have they been learned in the past.

(ii) It manifests second-order learning: Once it learns a new complex image or a new pattern of action, these patterns can themselves become associated with new compound patterns, allowing the organism to build up chains of associative links.

(iii) It can learn even if there is a time gap between the “neutral” complex stimulus and the reinforcement (the reward or punishment). Such “trace conditioning” requires that the memory of the neutral predictive stimulus is stored even when the reinforcing stimulus is transiently unperceived.

(iv) The value of a learned pattern can be readily changed: the reward or punishment value of a particular stimulus or a particular action is not fixed. It can change when the conditions change. Something that once predicted punishment (e.g., danger) can predict reward (safety) when conditions alter.

If an animal shows unlimited associative learning (that is, practically unrestricted learning) it means that all the capacities of consciousness are in place. Unification and differentiation are needed to construct compound stimuli (an apple is perceived as both red and round); global accessibility is needed to enable integration of information from multiple systems (e.g., the visual, olfactory, memory and evaluative systems — the red apple has a specific fragrance and following past experience is expected to be rewarding); selective attention is needed to pick these stimuli out from the background (e.g., ignore green or badly smelling apples and pick only the red fragrant ones); intentionality is needed, since the system maps or represents stimuli and the relations between them (e.g., the animal has a cognitive map of its environment); integration over time is needed for being able to learn even when there is a time gap between the neutral and rewarding stimulus; a flexible evaluation system is needed to make context-dependent learning possible (e.g., alter the value of a stimulus from punishing to rewarding); embodied agency is needed for exploring the world and for learning associations between actions; a “self,” entailing a stable point of view, is needed to compare stimuli and actions from the same perspective, and self/world distinction is needed so that the organism will not confuse stimuli generated by its own actions with stimuli generated by the external world. An animal with UAL is able to exhibit many complex behaviors, and can attain many different goals. Moreover, there is evidence that an animal can manifest UAL only when it is conscious. UAL is therefore a good transition marker for consciousness.

The Origins of Suffering

Ecclesiastes said: “For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.” Knowledge and suffering are also entangled in the myth of original sin, in Aeschylus’s “Agamemnon,” and in the myth of the eternally suffering Prometheus who blessed humans with the civilizing power of fire. What was the price of the knowledge-through-feelings that UAL inflicted on animals?

Like all great innovations, UAL opened a Pandora’s box of new challenges and problems. We believe that the greatest problem stemmed from overlearning: since parts of a sensory image can have different values (neutral, beneficial, life-threatening) in different conditions, false alarms are very likely. For example, for a fish, a particular pattern of vibrations combined with a particular pattern of colors can indicate a dangerous predator, while the color pattern alone and the vibration pattern alone may sometimes be associated with a nonthreatening passing animal. But since the rapid flight that the vibration or color pattern elicits is less costly than deathly injury, flight is preferable even if the vibration or color patterns turns out to be nonthreatening on most occasions. It is surely better to err on the side of caution. Randolph Nesse called the adaptive logic of erring on the side of caution the “smoke detector principle.”

Chronic anxiety and stress are costly, leading not only to a waste of time and energy but also to a greater propensity for painful diseases.

The price of overreacting includes, however, anxiety, paranoia, neuroses. Chronic anxiety and stress are costly, leading not only to a waste of time and energy but also to a greater propensity for painful diseases. Nevertheless, the cost-benefit balance is on the side of knowledge — a wise, suffering animal is better off than a nonsuffering, doomed fool.

Animals that could mitigate the high costs of UAL without giving up its benefits would have a great advantage. The evolutionary elaboration of the ubiquitous stress response and the evolution of active forgetting are some of the ameliorating mechanisms that we expect to find in all associatively learning animals, and in particular, in UAL animals. Suffering was not eliminated, but it became more controlled.

Animals that could mitigate the high costs of UAL without giving up its benefits would have a great advantage. The evolutionary elaboration of the ubiquitous stress response and the evolution of active forgetting are some of the ameliorating mechanisms that we expect to find in all associatively learning animals, and in particular, in UAL animals. Suffering was not eliminated, but it became more controlled.

In the last paragraph of “On the Origin of Species,” Darwin wrote: “Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows.” It was in the Cambrian, we suggest, that the great war of nature began to involve suffering — the subjective experiencing of the anguish and pain that is entangled with knowledge.

The Evolution of Imagination

The first conscious animals explored and learned about their world and the effects of their actions by seeking the satisfactions of food, sex, and social bonding and avoiding the pains and fears imposed by predators, deprivation, and disease. Their explorations were guided by what they learned in the past, which, in turn, led to further learning and exploration.

Driven by learning, consciousness and cognition evolved further. In some lineages, selection for increased learning capacity led to the gradual evolution of imaginative, dreaming animals. They did not just learn about aspects of their world; they also learned about how events unfolded in time. They recalled past events— they could recall when and where a particular event happened, and they planned ahead by recombining aspects of their recollections and evaluating the planned, imagined event. These animals, which inhabit the third floor in Dennett’s generate-and-test tower, could imagine different scenarios and choose between them.

Here is a famous example: Western scrub jays cache (in many locations) different types of foodstuff, such as tasty worms that rot within a short time, and less-favored peanuts that stay edible for much longer. They later remember not only where they cached the different foods, but also when: they recover worms soon after caching, and peanuts when they return to feed long after caching. Interestingly, they are aware of the possibility of theft by other jays. They re- cache food if they were watched while caching, but only if they themselves are thieves!

There are many examples of imaginative planning by birds and mammals, and there are more limited examples of the imaginative ability of some fish, bees, and cuttlefish. It is likely that imagination evolved gradually and to different degrees in different species. Curiously, most imaginative animals are social. Are their social sensibilities related to their imaginative capacities? Whatever the answer and however striking animal imagination is, it remains in the private domain. The ability to communicate about what one imagines is peculiar to humans.

Original article here

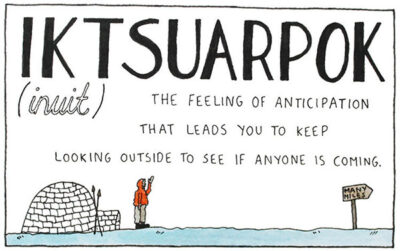

Sometimes we must turn to other languages to find le mot juste. Here are a whole bunch of foreign words with no direct English equivalent.

Sometimes we must turn to other languages to find le mot juste. Here are a whole bunch of foreign words with no direct English equivalent.

Time is one of those things that most of us take for granted. We spend our lives portioning it into work-time, family-time and me-time. Rarely do we sit and think about how and why we choreograph our lives through this strange medium. A lot of people only appreciate time when they have an experience that makes them realise how limited it is.

Time is one of those things that most of us take for granted. We spend our lives portioning it into work-time, family-time and me-time. Rarely do we sit and think about how and why we choreograph our lives through this strange medium. A lot of people only appreciate time when they have an experience that makes them realise how limited it is.

Ask people what they think they’ll look like in 25 years, and chances are they’ll mention how their parents looked at that age. And while genetics certainly play a part, research shows there’s more to the story. Only about 30% of what we see as aging is inherited, explains John Rowe, M.D., Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health.

Ask people what they think they’ll look like in 25 years, and chances are they’ll mention how their parents looked at that age. And while genetics certainly play a part, research shows there’s more to the story. Only about 30% of what we see as aging is inherited, explains John Rowe, M.D., Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health.

Many people see this as their best decade. During our 30s, we’re likely getting more settled in our careers and families, and according to one study our happiness levels are still actively increasing. This is also when making real lifestyle changes can help stave off long-term issues.

Many people see this as their best decade. During our 30s, we’re likely getting more settled in our careers and families, and according to one study our happiness levels are still actively increasing. This is also when making real lifestyle changes can help stave off long-term issues. Everything seems to come together when you hit your 40s. While your family life and career are likely at a high point, caring for aging parents and planning for the future can make it a stressful time.

Everything seems to come together when you hit your 40s. While your family life and career are likely at a high point, caring for aging parents and planning for the future can make it a stressful time. As your children head off to high school and college, now is when you think about how you would like to spend your time. Whether you focus on a new hobby, a volunteer project, or a career change, this decade is all about starting to concentrate on your own wants and needs.

As your children head off to high school and college, now is when you think about how you would like to spend your time. Whether you focus on a new hobby, a volunteer project, or a career change, this decade is all about starting to concentrate on your own wants and needs. Welcome to a new concept: freedom! Whether it’s thanks to becoming an empty nester, being newly retired, or just shaking off societal expectations, it’s all about you from now on. Here’s to prioritizing your mental and physical well-being!

Welcome to a new concept: freedom! Whether it’s thanks to becoming an empty nester, being newly retired, or just shaking off societal expectations, it’s all about you from now on. Here’s to prioritizing your mental and physical well-being!