Limiting beliefs are your beliefs about reality that restrict what you can experience in life, or attract, or become. Working with exposing limiting beliefs is the perfect antidote to use when you are feeling stuck with what life is throwing at you. Any negative, repeated pattern of experience is ultimately asking you to wake up to your true nature, and stop limiting yourself.

Ironically, most of us use a repeating pattern as an excuse to close down more and feel less. However, until the pattern gets to be so intense that we have no choice but to try something new, we stay stuck in a limiting belief. When we do try something new and actually try to change, but the pattern remains, we know without a doubt that our habitual way of dealing with a problem is a limited belief that needs to be challenged.

Reality Check

Let’s face it. We all have limiting beliefs that define our experience of and expression of self in the world. We all have limits to what we can experience and stay sane, connected, and alive. We also have limits to what we are willing to believe or not believe about reality itself.

Limits exist for a reason. All people have a unique relationship to how their belief system is limited in a way authentic to their soul path. Limiting beliefs become a detriment when there is a perceived loss of choice, perspective, and possibility to live one’s full life experience, making it impossible to live the life we want. We then use this repeated life pattern as an excuse to close down and give up because we are unaware of the limiting beliefs perpetuating it.

In contrast, we could use limiting beliefs to question what we experience, feel those repressed emotions, and open to more possibility in life. A simple limiting belief that I have challenged in my life is that I am supposed to be happy all the time. This limiting belief led me to friendships that did not feel satisfying because I was not expressing who I really was. I began to challenge myself simply by answering the often asked question — “How are you?” — with honesty, especially around people I wanted to have more fulfilling friendships with. The repressed emotions around my limiting belief were related to shame and fear of humiliation. As I began to share myself more, I had to feel into my fear. By challenging this belief and withstanding the emotion, I now have a better sense of when I am truly happy versus when I am not, and I also have friends I trust with my true self.

It is understandable to want to avoid the message behind difficult emotions. Existential emotions are a stretch for us to trust tapping into, and our conscious mind does not like when unconscious material arises; it feels greater than us. Disassociating, fantasizing, judging, blaming, gaslighting, or disconnecting are all reactions we will justify to avoid the change that unwanted emotions are asking us to embrace. But, we can choose to break the cycle by searching internally for limiting beliefs and identifying their effect on our lives, a process of maturation. Ultimately this choice is always our own. Choice is one of life’s gifts.

Steps To Shift Limiting Beliefs

There’s a good chance that any time you don’t want to take responsibility for your emotions (or want to accuse someone of not taking responsibility for theirs) an opportunity exists to explore a limiting belief of your own. This is about waking yourself up. There is nothing quite like breaking a limiting belief and having a new pattern arise where more is possible. Suddenly there is a freedom to be who you want to be. A piece of your soul expands and old emotional reactions no longer land as heavily. Doors open that were previously hidden; self-trust develops.

To start identifying limiting beliefs, simply begin the process of acknowledging more responsibility towards what you attract in life and how you process reality. Bringing awareness to limiting beliefs and starting to make different choices will initiate change in stuck cycles of your life.

One of the easiest places to look for limiting beliefs are in massive generalizations we make about reality in our own head. Try filling out the following statements with your view on reality — “just the way it is.” Take your time honestly considering your spontaneous, authentic responses to each prompt.

People are…(my own example might be here: People are scary. They won’t like me for who I am)

The world is…(my own example here might be: The world is a dangerous place.)

Relationships are…

Friends are…

Science is…

Religion is…

Medicine is…

Alternative medicine is…

Men are…

Women are…

Friends are…

Now carefully notice any underlying themes to your unique limiting beliefs. It is important to understand how your own beliefs come together to protect your core wound, which in turn protects your core self. I have a core wound around safety and self-expression. I have spiraled into this limiting belief over and over again on my healing journey. Every time I come up against something that limits my self-expression or ability to feel safe, I look towards my own internal limiting beliefs and allow myself to feel the emotion. Limiting beliefs do have a purpose as a means of protection. We are meant to have them, and meant to shift out of them if we want to make that choice. We can choose to get past our limiting beliefs or get stuck in them. The choice is always ours.

Original article here

IBS is far more common than IBD, affecting an estimated 70 million Americans. Symptoms of IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), a functional GI disease, include frequent:

IBS is far more common than IBD, affecting an estimated 70 million Americans. Symptoms of IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), a functional GI disease, include frequent:

The electrons are essentially drawn across the cytochrome oxidase system by the oxygen at the positive pole of the intracellular battery. The more oxygen in the system, the stronger the pull. Breathing exercises, eating high-oxygen foods, and living in atmospherically clean, high-oxygen environments increases our overall oxygen content. The cytochrome oxidase system exists in every cell and requires electron energy to function. This electron energy comes from plant foods as well as what we directly absorb. When the food is cooked, the basic harmonic resonance pattern of the living electron energy of the live food is at least partially destroyed. Once understanding this scientific evidence, the logical step is to eat high-electron foods such as fruits, vegetables, raw nuts and seeds, and sprouted or soaked grains. People who eat refined, cooked, highly processed foods diminish the amount of solar electrons energizing the system.

The electrons are essentially drawn across the cytochrome oxidase system by the oxygen at the positive pole of the intracellular battery. The more oxygen in the system, the stronger the pull. Breathing exercises, eating high-oxygen foods, and living in atmospherically clean, high-oxygen environments increases our overall oxygen content. The cytochrome oxidase system exists in every cell and requires electron energy to function. This electron energy comes from plant foods as well as what we directly absorb. When the food is cooked, the basic harmonic resonance pattern of the living electron energy of the live food is at least partially destroyed. Once understanding this scientific evidence, the logical step is to eat high-electron foods such as fruits, vegetables, raw nuts and seeds, and sprouted or soaked grains. People who eat refined, cooked, highly processed foods diminish the amount of solar electrons energizing the system.

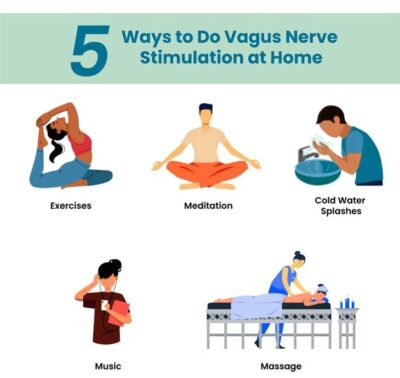

Singing, humming, chanting and even gargling can improve vagal tone because the vagus nerve controls your vocal cords and the muscles at the back of your throat, explains Dr Ravindran. A brain imaging study even found that the humming involved in the meditation chant ‘om’ reduced activity in areas of the brain associated with depression.

Singing, humming, chanting and even gargling can improve vagal tone because the vagus nerve controls your vocal cords and the muscles at the back of your throat, explains Dr Ravindran. A brain imaging study even found that the humming involved in the meditation chant ‘om’ reduced activity in areas of the brain associated with depression.