A desire to seek spiritual wisdom and a reassuring connection to the creator is evident throughout history in most cultures and traditions. Humans have tried to understand the origin of life and the source of their own being since the beginning of recorded time. Akasha is an ancient Sanskrit word for “source,” referring to the essence of the creator’s source, characterized by many traditions as the essence of love.

When we direct our minds, emotional and spirit to self-love, we accept a natural, loving, healing presence in our lives; this is when miracles happen. They aren’t really miracles outside of nature, but Illness, disease and loss are often a call from our soul to redirect our lives. When we are living our lives connected to our source in love, that natural way of living brings us back to health and a sense of well-being. It feels like a miracle to live from our source in love.

Agape or akashic spiritual love is about our connection to our spirit, our soul and the creator (infinite intelligence, love and light). This is a reciprocal relationship. This love speaks to a constant influx of spiritual energy that sustains our etheric, emotional, mental and physical bodies, which combine to create our self in this life. This love is the basis of the mystical essence of all religions, but in itself is not a religious belief system. This is the quantum field or the akashic essence of creation, where all potential exists and all creation is born from.

While we are mostly unconscious of this flow, we are created to exercise free will concerning how we direct and conduct our life. We can become conscious of this flow and learn to direct it as a loving, healthy, and sustaining current in our life. We are given the choice to connect or not to connect to this spiritual love and the guidance it contains. Our self-awareness and our ability to recognize our needs and care for ourselves is in direct proportion to our capacity to allow this akashic spiritual energy to sustain and elevate our lives.

The akashic energy, like a universal ether, fills the world — every being and even the very air we breathe. The akashic energy resides within your body, activated and used by your spirit throughout your life. You can choose to consciously access and develop this energy as you gain a higher awareness of your spiritual nature.

Within the akashic energy field is a receptive intelligence that embeds all experiences and events into an energetic library of information — the wisdom of all creation. Encoded vibrationally into the fabric of space, some have likened the mechanism as similar to how holograms are created. I see the records as energetic packages of information.

The records containing the macrocosm and microcosm of your life — the big picture of your soul’s plan and purpose, and the very personal information of the details of your daily life — are all retained in this akashic field. This includes every thought, word, feeling and action throughout your entire lifetime, and even before this incarnation. Accessing this information is done in small bytes of information, which you can benefit from by learning about and developing a more complete sense of yourself. What are the patterns you repeat over and over in this lifetime, and perhaps in a previous lifetime that need healing? Chin up, you have been given all the time and experience you need to learn, grow, and refine the sheen of your human presence here on Earth. Now is a good time to roll up your sleeves and access your akashic records. When you access the knowledge and creative energy in your records, you learn how to heal yourself and become a creator of positive outcomes in your own life.

You have the tools and potential within your consciousness to access your personal history and soul records within the akashic field. With this access, you gain understanding about the wounded places where your soul has disconnected from its source of love through trauma or misunderstood experiences in this life or past lives. You can reclaim and heal these wounded parts of self as you access the akashic field of infinite intelligence and love.

Accessing the healing capacity within this realm requires a flow of exchange between you and the akashic energy done with deep respect and humility. The entrance fee for stepping onto this healing path is taking ownership of your thoughts and choices with clear intentions to raise your vibration above blame, shame, victimization and guilt. These sorts of excuses will only keep you attached to your pain and prevent your healing. Honesty, forgiveness, curiosity and a willingness to open to spirit will elevate your vibration, and thus your access to akashic intelligence and all its healing, nurturing love, leading you right back home.

Original article here

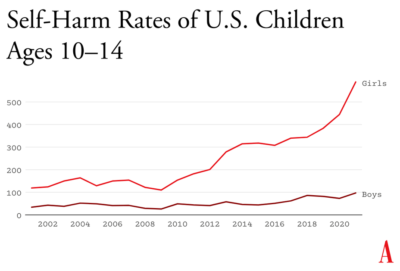

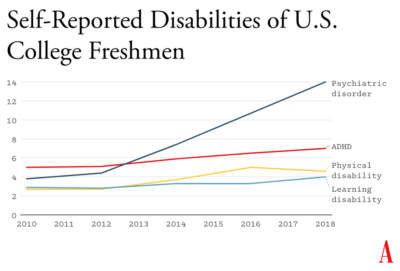

In recent decades, however, Congress has not been good at addressing public concerns when the solutions would displease a powerful and deep-pocketed industry. Governors and state legislators have been much more effective, and their successes might let us evaluate how well various reforms work. But the bottom line is that to change norms, we’re going to need to do most of the work ourselves, in neighborhood groups, schools, and other communities.

In recent decades, however, Congress has not been good at addressing public concerns when the solutions would displease a powerful and deep-pocketed industry. Governors and state legislators have been much more effective, and their successes might let us evaluate how well various reforms work. But the bottom line is that to change norms, we’re going to need to do most of the work ourselves, in neighborhood groups, schools, and other communities. I have been pals with the Universe for quite some time now. It wasn’t always that way, but it sure has been over the last 30 years after discovering that all kinds of super intelligence dwelt in the spaces between the stars.

I have been pals with the Universe for quite some time now. It wasn’t always that way, but it sure has been over the last 30 years after discovering that all kinds of super intelligence dwelt in the spaces between the stars.