We’ve often thought about muscle as a thing that exists separately from intellect—and perhaps that is even oppositional to it, one taking resources from the other. The truth is, our brains and muscles are in constant conversation with each other, sending electrochemical signals back and forth. In a very tangible way, our lifelong brain health depends on keeping our muscles moving.

Skeletal muscle is the type of muscle that allows you to move your body around; it is one of the biggest organs in the human body. It is also an endocrine tissue, which means it releases signaling molecules that travel to other parts of your body to tell them to do things. The protein molecules that transmit messages from the skeletal muscle to other tissues—including the brain—are called myokines.

Myokines are released into the bloodstream when your muscles contract, create new cells, or perform other metabolic activities. When they arrive at the brain, they regulate physiological and metabolic responses there, too. As a result, myokines have the ability to affect cognition, mood, and emotional behavior. Exercise further stimulates what scientists call muscle-brain “cross talk,” and these myokine messengers help determine specific beneficial responses in the brain. These can include the formation of new neurons and increased synaptic plasticity, both of which boost learning and memory.

In these ways, strong muscles are essential to healthy brain function.

In young muscle, a small amount of exercise triggers molecular processes that tell the muscle to grow. Muscle fibers sustain damage through strain and stress, and then repair themselves by fusing together and increasing in size and mass. Muscles get stronger by surviving each series of little breakdowns, allowing for regeneration, rejuvenation, regrowth. As we age, the signal sent by exercise becomes much weaker. Though it’s more difficult for older people to gain and maintain muscle mass, it’s still possible to do so, and that maintenance is critical to supporting the brain.

Even moderate exercise can increase metabolism in brain regions important for learning and memory in older adults. And the brain itself has been found to respond to exercise in strikingly physical ways. The hippocampus, a brain structure that plays a major role in learning and memory, shrinks in late adulthood; this can result in an increased risk for dementia. Exercise training has been shown to increase the size of the hippocampus, even late in life, protecting against age-related loss and improving spatial memory.

Further, there is substantial evidence that certain myokines have sex-differentiated neuroprotective properties. For example, the myokine irisin is influenced by estrogen levels, and postmenopausal women are more susceptible to neurological diseases, which suggests that irisin may also have an important role in protecting neurons against age-related decline.

Studies have shown that even in people with existing brain disease or damage, increased physical activity and motor skills are associated with better cognitive function. People with sarcopenia, or age-related muscle atrophy, are more likely to suffer cognitive decline. Mounting evidence shows that the loss of skeletal muscle mass and function leaves the brain more vulnerable to dysfunction and disease; as a counter to that, exercise improves memory, processing speed, and executive function, especially in older adults. (Exercise also boosts these cognitive abilities in children.)

There’s a robust molecular language being spoken between your muscles and your brain. Exercise helps keep us fluent in that language, even into old age.

Original article here

Our eyes are continuously bombarded by an enormous amount of visual information – millions of shapes, colours and ever-changing motion all around us. For the brain, this is no easy feat. On the one hand, the visual world alters continuously because of changes in light, viewpoint and other factors. On the other, our visual input constantly changes due to blinking and the fact that our eyes, head and body are frequently in motion.

Our eyes are continuously bombarded by an enormous amount of visual information – millions of shapes, colours and ever-changing motion all around us. For the brain, this is no easy feat. On the one hand, the visual world alters continuously because of changes in light, viewpoint and other factors. On the other, our visual input constantly changes due to blinking and the fact that our eyes, head and body are frequently in motion. For many of us, decluttering serves as a sort of mental palette cleanser. Stressed out? Tidy your apartment. Unfocused and frazzled? Clear the mess on your desk. Down in the dumps? Reorganize your closet for a sense of accomplishment.

For many of us, decluttering serves as a sort of mental palette cleanser. Stressed out? Tidy your apartment. Unfocused and frazzled? Clear the mess on your desk. Down in the dumps? Reorganize your closet for a sense of accomplishment. Believe it or not, you may find yourself looking for your next organizational project after just seven days or so. “System creation can provide ongoing motivation—it builds on itself,” Dorfman notes. “If you design an entryway space equipped with a place for your coat, keys, and bag, you’ve mitigated future misplacements. The sense of mastery and competence prompts the mind to want more.”

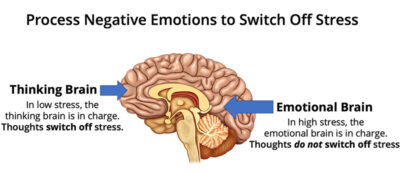

Believe it or not, you may find yourself looking for your next organizational project after just seven days or so. “System creation can provide ongoing motivation—it builds on itself,” Dorfman notes. “If you design an entryway space equipped with a place for your coat, keys, and bag, you’ve mitigated future misplacements. The sense of mastery and competence prompts the mind to want more.” If you’ve been stressed out and ignoring it—isn’t everyone stressed right now?— it could be time to do something about it. That’s because even though you may be basically healthy, tension is doing its stealthy damage. The latest evidence? Researchers have linked high levels of the stress hormone cortisol to brain shrinkage and impaired memory in healthy middle-aged adults. And get this: The effect was more pronounced in women than in men.

If you’ve been stressed out and ignoring it—isn’t everyone stressed right now?— it could be time to do something about it. That’s because even though you may be basically healthy, tension is doing its stealthy damage. The latest evidence? Researchers have linked high levels of the stress hormone cortisol to brain shrinkage and impaired memory in healthy middle-aged adults. And get this: The effect was more pronounced in women than in men. Priem has found that problems arise between couples when each person has a different perception of what’s stressful. The result: When people are really tense, their partners aren’t necessarily motivated to offer support if they think, If I were in this situation, I wouldn’t consider it that big a deal. So how do you get the response you want when you need it?

Priem has found that problems arise between couples when each person has a different perception of what’s stressful. The result: When people are really tense, their partners aren’t necessarily motivated to offer support if they think, If I were in this situation, I wouldn’t consider it that big a deal. So how do you get the response you want when you need it?

A friend of mine spends 20 to 30 minutes a day solving Sudoku puzzles. He says it improves his speed of mental processing and makes him, well, smarter.

A friend of mine spends 20 to 30 minutes a day solving Sudoku puzzles. He says it improves his speed of mental processing and makes him, well, smarter. We are all storytellers; we make sense out of the world by telling stories. And science is a great source of stories. Not so, you might argue. Science is an objective collection and interpretation of data. I completely agree. At the level of the study of purely physical phenomena, science is the only reliable method for establishing the facts of the world.

We are all storytellers; we make sense out of the world by telling stories. And science is a great source of stories. Not so, you might argue. Science is an objective collection and interpretation of data. I completely agree. At the level of the study of purely physical phenomena, science is the only reliable method for establishing the facts of the world. Our brain is always active and it is certainly a good idea to nourish it. We can maximise its potential with simple practices.

Our brain is always active and it is certainly a good idea to nourish it. We can maximise its potential with simple practices.