Thomas Ormerod’s team of security officers faced a seemingly impossible task. At airports across Europe, they were asked to interview passengers on their history and travel plans. Ormerod had planted a handful of people arriving at security with a false history, and a made-up future – and his team had to guess who they were. In fact, just one in 1000 of the people they interviewed would be deceiving them. Identifying the liar should have been about as easy as finding a needle in a haystack.

Using previous methods of lie detection, you might as well just flip a coin

So, what did they do? One option would be to focus on body language or eye movements, right? It would have been a bad idea. Study after study has found that attempts – even by trained police officers – to read lies from body language and facial expressions are more often little better than chance. According to one study, just 50 out of 20,000 people managed to make a correct judgement with more than 80% accuracy. Most people might as well just flip a coin.

Ormerod’s team tried something different – and managed to identify the fake passengers in the vast majority of cases. Their secret? To throw away many of the accepted cues to deception and start anew with some startlingly straightforward techniques.

Over the last few years, deception research has been plagued by disappointing results. Most previous work had focused on reading a liar’s intentions via their body language or from their face – blushing cheeks, a nervous laugh, darting eyes. The most famous example is Bill Clinton touching his nose when he denied his affair with Monica Lewinsky – taken at the time to be a sure sign he was lying. The idea, says Timothy Levine at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, was that the act of lying provokes some strong emotions – nerves, guilt, perhaps even exhilaration at the challenge – that are difficult to contain. Even if we think we have a poker face, we might still give away tiny flickers of movement known as “micro-expressions” that might give the game away, they claimed.

The problem is the huge variety of human behaviour; there is no universal dictionary of body language

Yet the more psychologists looked, the more elusive any reliable cues appeared to be. The problem is the huge variety of human behaviour. With familiarity, you might be able to spot someone’s tics whenever they are telling the truth, but others will probably act very differently; there is no universal dictionary of body language. “There are no consistent signs that always arise alongside deception,” says Ormerod, who is based at the University of Sussex. “I giggle nervously, others become more serious, some make eye contact, some avoid it.” Levine agrees: “The evidence is pretty clear that there aren’t any reliable cues that distinguish truth and lies,” he says. And although you may hear that our subconscious can spot these signs even if they seem to escape our awareness, this too seems to have been disproved.

Despite these damning results, our safety often still hinges on the existence of these mythical cues. Consider the screening some passengers might face before a long-haul flight – a process Ormerod was asked to investigate in the run up to the 2012 Olympics. Typically, he says, officers will use a “yes/no” questionnaire about the flyer’s intentions, and they are trained to observe “suspicious signs” (such as nervous body language) that might betray deception. “It doesn’t give a chance to listen to what they say, and think about credibility, observe behaviour change – they are the critical aspects of deception detection,” he says. The existing protocols are also prone to bias, he says – officers were more likely to find suspicious signs in certain ethnic groups, for instance. “The current method actually prevents deception detection,” he says.

Clearly, a new method is needed. But given some of the dismal results from the lab, what should it be? Ormerod’s answer was disarmingly simple: shift the focus away from the subtle mannerisms to the words people are actually saying, gently probing the right pressure points to make the liar’s front crumble.

Ormerod and his colleague Coral Dando at the University of Wolverhampton identified a series of conversational principles that should increase your chances of uncovering deceit:

Use open questions. This forces the liar to expand on their tale until they become entrapped in their own web of deceit.

Employ the element of surprise. Investigators should try to increase the liar’s “cognitive load” – such as by asking them unanticipated questions that might be slightly confusing, or asking them to report an event backwards in time – techniques that make it harder for them to maintain their façade.

Watch for small, verifiable details. If a passenger says they are at the University of Oxford, ask them to tell you about their journey to work.

Liar vs liar

It takes one to know one

Ironically, liars turn out to be better lie detectors. Geoffrey Bird at University College London and colleagues recently set up a game in which subjects had to reveal true or false statements about themselves. They were also asked to judge each other’s credibility. It turned out that people who were better at telling fibs could also detect others’ tall tales, perhaps because they recognised the tricks.

Observe changes in confidence. Watch carefully to see how a potential liar’s style changes when they are challenged: a liar may be just as verbose when they feel in charge of a conversation, but their comfort zone is limited and they may clam up if they feel like they are losing control.

The aim is a casual conversation rather than an intense interrogation. Under this gentle pressure, however, the liar will give themselves away by contradicting their own story, or by becoming obviously evasive or erratic in their responses. “The important thing is that there is no magic silver bullet; we are taking the best things and putting them together for a cognitive approach,” says Ormerod.

Ormerod openly admits his strategy might sound like common sense. “A friend said that you are trying to patent the art of conversation,” he says. But the results speak for themselves. The team prepared a handful of fake passengers, with realistic tickets and travel documents. They were given a week to prepare their story, and were then asked to line up with other, genuine passengers at airports across Europe. Officers trained in Ormerod and Dando’s interviewing technique were more than 20 times more likely to detect these fake passengers than people using the suspicious signs, finding them 70% of the time.

“It’s really impressive,” says Levine, who was not involved in this study. He thinks it is particularly important that they conducted the experiment in real airports. “It’s the most realistic study around.”

The art of persuasion

Levine’s own experiments have proven similarly powerful. Like Ormerod, he believes that clever interviews designed to reveal holes in a liar’s story are far better than trying to identify telltale signs in body language. He recently set up a trivia game, in which undergraduates played in pairs for a cash prize of $5 for each correct answer they gave. Unknown to the students, their partners were actors, and when the game master temporarily left the room, the actor would suggest that they quickly peek at the answers to cheat on the game. A handful of the students took him up on the offer.

One expert was even correct 100% of the time, across 33 interviews

Afterwards, the students were all questioned by real federal agents about whether or not they had cheated. Using tactical questions to probe their stories – without focusing on body language or other cues – they managed to find the cheaters with more than 90% accuracy; one expert was even correct 100% of the time, across 33 interviews – a staggering result that towers above the accuracy of body language analyses. Importantly, a follow-up study found that even novices managed to achieve nearly 80% accuracy, simply by using the right, open-ended questions that asked, for instance, how their partner would tell the story.

Indeed, often the investigators persuaded the cheaters to openly admit their misdeed. “The experts were fabulously good at this,” says Levine. Their secret was a simple trick known to masters in the art of persuasion: they would open the conversation by asking the students how honest they were. Simply getting them to say they told the truth primed them to be more candid later. “People want to think of being honest, and this ties them into being cooperative,” says Levine. “Even the people who weren’t honest had difficulty pretending to be cooperative [after this], so for the most part you could see who was faking it.”

Another trick is to ask people how honest they are

Clearly, such tricks may already be used by some expert detectives – but given the folklore surrounding body language, it’s worth emphasising just how powerful persuasion can be compared to the dubious science of body language. Despite their successes, Ormerod and Levine are both keen that others attempt to replicate and expand on their findings, to make sure that they stand up in different situations. “We should watch out for big sweeping claims,” says Levine.

Although the techniques will primarily help law enforcement, the same principles might just help you hunt out the liars in your own life. “I do it with kids all the time,” Ormerod says. The main thing to remember is to keep an open mind and not to jump to early conclusions: just because someone looks nervous, or struggles to remember a crucial detail, does not mean they are guilty. Instead, you should be looking for more general inconsistencies.

There is no foolproof form of lie detection, but using a little tact, intelligence, and persuasion, you can hope that eventually, the truth will out.

Original article here

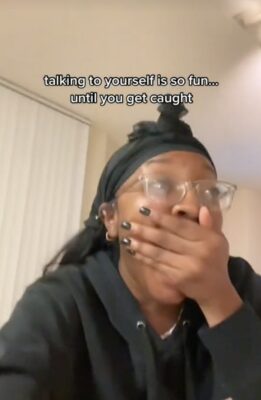

Everyone has a few comforting quirks that they only indulge in behind closed doors. For some, it’s lying on the floor to relax. For others, it’s talking to themselves out loud. These unhinged habits might seem embarrassing, especially if you get caught in the act, but then you go on social media and realize there are dozens — and sometimes even hundreds of thousands — of other people just like you.

Everyone has a few comforting quirks that they only indulge in behind closed doors. For some, it’s lying on the floor to relax. For others, it’s talking to themselves out loud. These unhinged habits might seem embarrassing, especially if you get caught in the act, but then you go on social media and realize there are dozens — and sometimes even hundreds of thousands — of other people just like you.

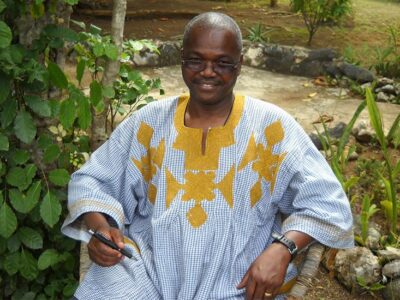

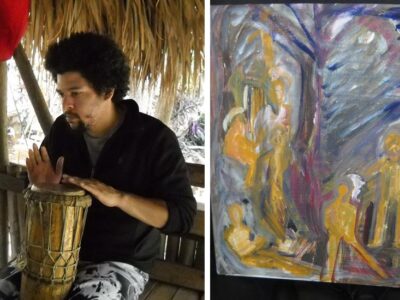

Malidoma is from a collectivist society. Born into the Dagara tribe in Burkina Faso, he is the grandson of a renowned healer, who travels around the world but is based in the U.S. Malidoma sees himself as a bridge between his culture and the United States, existing to “bring the wisdom of our people to this part of the world.” Malidoma’s “career”—he chuckles at the term—is some combination of cultural ambassador, homeopath, and sage. He travels the country doing rituals and consultations, writing books, and giving speeches. He has three master’s degrees and two doctorates from Brandeis University. Sometimes he calls himself a “shaman,” because people know what that means (sort of) and it’s similar to his title back in Burkina Faso—a titiyulo, one who “constantly inquires with other dimensions.”

Malidoma is from a collectivist society. Born into the Dagara tribe in Burkina Faso, he is the grandson of a renowned healer, who travels around the world but is based in the U.S. Malidoma sees himself as a bridge between his culture and the United States, existing to “bring the wisdom of our people to this part of the world.” Malidoma’s “career”—he chuckles at the term—is some combination of cultural ambassador, homeopath, and sage. He travels the country doing rituals and consultations, writing books, and giving speeches. He has three master’s degrees and two doctorates from Brandeis University. Sometimes he calls himself a “shaman,” because people know what that means (sort of) and it’s similar to his title back in Burkina Faso—a titiyulo, one who “constantly inquires with other dimensions.”

I had grown up a good Sikh boy: I wore a turban, didn’t cut my hair, didn’t drink or smoke. The idea of a god that acted in the world had long seemed implausible, yet it wasn’t until I started studying evolution in earnest that the strictures of religion and of everyday conventions began to feel brittle. By my junior year of college, I thought of myself as a materialist, open-minded but skeptical of anything that smacked of the supernatural. Celebrationism came soon after. It expanded from an ethical road map into a life philosophy, spanning aesthetics, spirituality, and purpose. By the end of my senior year, I was painting my fingernails, drawing swirling mehndi tattoos on my limbs, and regularly walking without shoes, including during my college graduation. “Why, Manvir?” my mother asked, quietly, and I launched into a riff about the illusory nature of normativity and about how I was merely a fancy organism produced by cosmic mega-forces.

I had grown up a good Sikh boy: I wore a turban, didn’t cut my hair, didn’t drink or smoke. The idea of a god that acted in the world had long seemed implausible, yet it wasn’t until I started studying evolution in earnest that the strictures of religion and of everyday conventions began to feel brittle. By my junior year of college, I thought of myself as a materialist, open-minded but skeptical of anything that smacked of the supernatural. Celebrationism came soon after. It expanded from an ethical road map into a life philosophy, spanning aesthetics, spirituality, and purpose. By the end of my senior year, I was painting my fingernails, drawing swirling mehndi tattoos on my limbs, and regularly walking without shoes, including during my college graduation. “Why, Manvir?” my mother asked, quietly, and I launched into a riff about the illusory nature of normativity and about how I was merely a fancy organism produced by cosmic mega-forces.