In all the time I spent with Joanna Hall, she barely stopped walking. I would see her coming towards me in Kensington Gardens, London, gliding past the other strollers as if she alone were on a moving walkway. When she reached me, I would fall into step and off we would walk, for an hour. At the end, Hall would stride into the distance and keep walking, for all I knew, until we met the following week.

Hall’s WalkActive system, a comprehensive fitness programme based around walking, aims to improve posture, increase speed, reduce stress on joints and deliver fitness, turning a stroll into a workout and changing the way you walk for ever. She says she can teach it to me, and we have set aside four weeks for my education.

It is easy to be sceptical when someone claims you can reap huge health benefits simply by learning to walk better. You think: I’m already good at walking. And sometimes, I walk a long way.

But according to Hall, a fitness expert who enjoyed a three-year stint on ITV’s This Morning, almost nobody is good at walking: not you, not me and not all the other people in the park, who provide endless lessons in poor technique. I notice they are still managing to get where they are going. Are we not in danger of overthinking something people do without thinking?

Hall tells me: “If you ask someone, ‘When you go for a walk, do you enjoy it?’, they will say, ‘Yes’, but if you ask, ‘Do you ever experience discomfort in your lower back?’, quite a few people will say, ‘Yeah, I do get discomfort in my back, or I feel it when I get out of bed, or I’m tight in my achilles or stiff in my shoulder.’ And those are all indicators that an individual is walking sub-optimally.”

What are we doing wrong? Most of us, she says, tend to walk by stepping into the space in front of us. “I want you to think about walking out of the space behind you.”

If that sounds a bit abstract to you – as it did to me, at first – think about it this way: good walking is an act of propulsion, of pushing yourself forward off your back foot. Bad walking – my kind of walking – is overly dependent on traction: pulling yourself along with your front foot. This shortens your stride, relies too much on your hip flexors and puts unnecessary stress on your knees.

The struggle to get me to absorb this basic concept takes up most of our first hour together. My opening question about optimal walking was: “Will I look mad?” I imagined great loping strides and pumping arms.

“I promise you, you won’t look mad,” Hall said. But when you stroll haltingly through a public park while someone instructs you on heel placement, you do attract a certain amount of attention. People think: poor man, he’s having to learn to walk all over again.

They are not wrong. It takes a tremendous amount of concentration to do something so basic, and so ingrained, in a different way. It begins with the feet: I am trying to maintain a flexible, open ankle, to leave my back foot on the ground for longer, and to peel it away, heel first, as if it were stuck in place with Velcro.

“Feel the peel,” says Hall. “Feel. The. Peel.”

Second come the hips: I need to increase the distance between my pelvis and my ribs, standing tall and creating more flexibility through my torso. Then my neck: there needs to be more distance between my collarbone and my earlobes. I need to think about maintaining all of these things at the same time.

Hall acknowledges that, for beginners, there will be what she calls “Buckaroo! moments” – named after the children’s game featuring a put-upon, spring-loaded mule – when too much information causes a system overload. This happens to me when, while I’m busy monitoring my feet, my stride, my hips and my neck, Hall suggests that the pendular arc of my arms could do with a bit more backswing.

“What?” I ask. My rhythm collapses. My shoulders slump. My ribs sink. My right heel scuffs the pavement. I can feel, for the first time, just how not good my normal walking is. How did I get like this?

Hominids have been walking on two legs for more than 4m years. It is more energy efficient than walking on all fours, and it keeps your hands free for other tasks, but this advance came with its own problems. Studies suggest that some common human back problems may stem from spinal characteristics inherited from our knuckle-walking ancestors.

Your walk can also be affected by the way you sit, especially when you sit a lot: favouring one hip over another at your desk, or in your car. “Small things we’re doing consistently create that default neuromuscular pattern, which is just a little bit out of sync,” says Hall. “And it may not translate into anything, but over a period of time it can manifest itself as discomfort.”

Also, she tells me, my shoes are wrong.

Between our meetings, I work my way through Hall’s WalkActive app, a mix of instructional videos, audio coaching sessions and timed walks set to music of varying speeds. At this stage, I’m still perfecting my technique. “Imagine that maybe you have a Post-it note on the sole of your foot,” Hall says in my headphones as I turn the corner at the end of my road. “And you want to show the message on the Post-it note to the person behind you.” Feel the peel, I think. Read my heel.

Hall conceived the WalkActive system more than a decade ago, during the double whammy of pregnancy and appendicitis. “As soon as I was pregnant, even prior to having the appendicitis challenge, I never felt I wanted to do high-impact activity,” she says. “So walking was a natural thing for me to focus on.”

She later applied the techniques to her clients, but the regime she developed was originally for herself. She says: “It came from a personal space of wanting to rehab myself, to try to walk myself through rehab and walk myself through a fit pregnancy.”

Hall’s programme may be low-impact, but it is not low energy. By the end of our second session together, I am exhausted, because of the concentration required and the distance we have covered. A study that Hall commissioned showed that participants who completed a month of WalkActive training increased their walking speed by 24%. This alone amounts to a pretty big lifestyle adjustment – and you suddenly find that everyone is in your way. I’m not just faster, but taller, and my arms swing with a natural, easy rhythm, exuding a confidence wholly at odds with the rest of my personality. It feels, frankly, amazing.

One Friday morning, just before 7am, I join Hall’s twice-weekly WhatsApp group, along with several dozen other people also dialing in from around the country. I can hear birdsong in my earbuds as I walk out through my front door, while Hall guides us all through 30 minutes of brisk, optimal walking in real time.

“Leave that back foot on the floor,” she says, “so it’s a really sticky foot. Feel the peel.” I can feel it, I think, although I’m actually stuck at a level crossing.

By our fourth and final meeting I have the right shoes, as recommended by Hall. They are ugly, but they have a flexible sole and enough width to allow the toes to spread when the foot is on the ground. Today, we are concentrating not on speed but on varying our pace, slowing it down and shortening the stride, without compromising technique. This is because, during our third meeting, I mentioned that on ordinary walks I found myself outpacing the people I was with.

“I like to say the technique has a dimmer switch,” Hall tells me as we glide past the Albert Memorial. “You can turn it up or down, but it’s always on.” She has mistaken my boast for a complaint. I didn’t mean that I feel bad for leaving my friends behind. I meant that I am done with those people.

Perhaps the most significant claim Hall makes is that, in terms of fitness, walking can be enough. It can complement other forms of exercise, such as yoga and Pilates, but if you don’t do anything else, improving your walk can still confer major health benefits.

“I’m not anti-running, I’m not anti-gyms, I think they all have a role to play,” she says. “But I also think, sometimes, if we just think about the simplest thing that we could all do, and just get people to do it better, even if someone doesn’t necessarily feel as if they want to walk for longer, even if they just looked at changing their walking technique and applied it to their commute, that can be powerful.”

This is the real question: whether, after four weeks of training and new £70 shoes, I will continue to walk like this forever. But after I leave Hall in the park, I cross the street with my head high, feeling the peel with every step, all the way to my train, in case she is behind me, watching.

Original article here

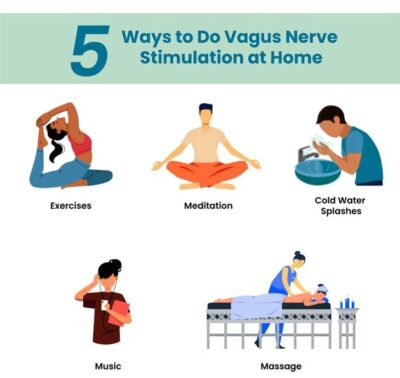

Singing, humming, chanting and even gargling can improve vagal tone because the vagus nerve controls your vocal cords and the muscles at the back of your throat, explains Dr Ravindran. A brain imaging study even found that the humming involved in the meditation chant ‘om’ reduced activity in areas of the brain associated with depression.

Singing, humming, chanting and even gargling can improve vagal tone because the vagus nerve controls your vocal cords and the muscles at the back of your throat, explains Dr Ravindran. A brain imaging study even found that the humming involved in the meditation chant ‘om’ reduced activity in areas of the brain associated with depression.

I began selling locally at first back in 2012, and now sell more and more online with the help of social media.

I began selling locally at first back in 2012, and now sell more and more online with the help of social media.