Recovering from a happy childhood can take a long time. It’s not often that I’m suspected of having had one. I grew up in Norman, Oklahoma, a daughter of immigrants. When I showed up at college and caught sight of other childhoods, I did pause and think: Why didn’t we grow our own tomatoes? Why did I watch so many episodes of “I Dream of Jeannie”? Who is Hermes? What is lacrosse? Was my childhood a dud? An American self-inspection was set in motion. Having lived for more than forty-five years, I finally understand how happy my childhood was.

Recovering from a happy childhood can take a long time. It’s not often that I’m suspected of having had one. I grew up in Norman, Oklahoma, a daughter of immigrants. When I showed up at college and caught sight of other childhoods, I did pause and think: Why didn’t we grow our own tomatoes? Why did I watch so many episodes of “I Dream of Jeannie”? Who is Hermes? What is lacrosse? Was my childhood a dud? An American self-inspection was set in motion. Having lived for more than forty-five years, I finally understand how happy my childhood was.

One might assume that my mother is to blame for this happiness, but I think my father has the stronger portion to answer for, though I only had the chance to know him for seventeen years before he died unexpectedly. He was an extoller of childhood, generally. I recall his saying to me once that the first eighteen years of life are the most meaningful and eventful, and that the years after that, even considered all together, can’t really compare.

The odd corollary was that he spoke very rarely of his own childhood. Maybe he didn’t want to brag. Even if he had told me more, I most likely wouldn’t have listened properly or understood much, because, like many children, I spent my childhood not really understanding who my parents were or what they were like. Though I collected clues. Century plants sometimes bloom after a decade, sometimes after two or three decades. I saw one in bloom recently, when my eight-year-old daughter pointed it out to me. I’m forty-six now, and much that my father used to say and embody has, after years of dormancy, begun to reveal itself in flower.

Growing up, I considered my father to be intelligent and incapable. Intelligent, because he had things to say about the Bosporus and the straits of Dardanelles. Incapable, because he ate ice cream from the container with a fork, and also he never sliced cheese, or used a knife in any way—instead, he tore things, like a caveman. Interestingly, he once observed that he didn’t think he would have lasted long as a caveman. This was apropos of nothing I could follow. He often seemed to assume that others were aware of the unspoken thoughts in his head which preceded speech. Maybe because his hearing was poor. He sat about two feet away from the television, with the volume on high. He also wore thick bifocal glasses. (In the seventies and early eighties, he wore tinted thick bifocal glasses.) The reason he wouldn’t have lasted long as a caveman, he said, was that his vision and his hearing meant that he would have been a poor hunter. “Either I would have died early on or maybe I would never have been born at all,” he said. The insight made him wistful.

If I had met my father as a stranger, I would have guessed him to be Siberian, or maybe Mongolian. He was more than six feet tall. His head was large and wide. His eyes seemed small behind his glasses. His wrists were delicate. I could encircle them, even with my child hands. His hair was silky, black, and wavy. He and my mother argued regularly about cutting his hair: she wanted to cut it; he wanted it to stay as it was. He was heavy the whole time I knew him, but he didn’t seem heavy to me. He seemed correctly sized. When he placed his hand atop my head, I felt safe, but also slightly squashed. He once asked me to punch his abdomen and tell him if it was muscular or soft. That was my only encounter with any vanity in him.

It would have been difficult for him if he had been vain, because he didn’t buy any of his own clothes, or really anything, not even postage stamps. Whenever there were clearance sales at the Dillard’s at the Sooner Fashion Mall, my mom and I would page through the folded button-up shirts, each in its cardboard sleeve, the way other kids must have flipped through LPs at record stores. We were looking for the rare and magical neck size of 17.5. If we found it, we bought it, regardless of the pattern. Button-ups were the only kind of shirts he wore, apart from the Hanes undershirts he wore beneath them. Even when he went jogging, he wore these button-ups, which would become soaked through with sweat. He thought it was amusing when I called him a sweatbomb, though I was, alas, aware that it was a term I had not invented. He appeared to think highly of almost anything I and my brother said or did.

He had a belt, and only one belt. It was a beige Izod belt, made of woven material for most of its length, and of leather for the buckle-and-clasp area. My dad wore this belt every day. Every day the alligator was upside down. How could it be upside down so consistently? He said that it was because he was left-handed. What did that have to do with anything? He showed me how he started with the belt oriented “correctly,” and held it in his left hand. But then, somehow, in the process of methodically threading it through his belt loops, it ended upside down. His demonstration was like watching a Jacob’s-ladder toy clatter down, wooden block by wooden block.

I loved Jacob’s ladders as a kid, I think because it took me so long to understand how they produced their illusion. And I also loved the story of Jacob’s ladder in the Bible, which was similarly confusing. Jacob dreams of a ladder between Heaven and earth, with angels going up and down it. Another night, Jacob wrestles with an angel, or with God, and to me this part also seemed to be as if in a dream, though we were meant to understand that Jacob’s hip was injured in real life. This is not Biblical scholarship, but I had the sense—from where? My Jewish education in Norman can perhaps best be summarized by the fact that my brother’s bar mitzvah is the only bar mitzvah I have attended—that Jacob was the brainy brother and Esau was the good hunter, with the hairy arms, and Jacob had stolen Esau’s birthright blessing by putting a hairy pelt on his arm and impersonating Esau before his father, Isaac, who was going blind. And yet we were supposed to be cheering for Jacob. And Jacob’s mother, Rivka—that was me!—had been the orchestrator of it all. What a sneak. Though it was also a classic story of a household that appeared to be run by the dad but, for more important purposes, was run by the mom.

My dad loved arguments. If he had been a different kind of man—more of an Esau—he probably would have loved a brawl, too. He sought out arguments, especially at work, where arguing was socially acceptable, since it was considered good science, and my father was a scientist. Fighting was a big pastime in my family, more broadly. Our motto for our road-trip vacations was: We pay money to fight. I remember once breaking down in tears and complaining that my mom, my dad, my brother—they all fought with one another. But no one ever wanted to fight with me. I was the youngest by six years.

I did not call my dad Dad but, rather, Tzvi, his first name, which is the Hebrew word for deer. I assume that my older brother started this. As best as I can deduce, Tzvi went to bed at about 4 A.M. and woke up at about 10 or 11 A.M. It was therefore my mom who made me breakfast—two Chessmen cookies and a cup of tea—and packed my lunch, and drove me to school, and bought my clothes, and did the laundry, and cleaned the house, and did all that for my brother and my dad, too, and did everything, basically, including have her own job. But if I thought about who I wanted to be when I grew up, and who I thought I was most like—it was my dad. My dad slept on many pillows, which I found comical and princess-like. (When I was twenty-three and in medical school, I realized that this was a classic sign of congestive heart failure.) He was a professor of meteorology at the University of Oklahoma, though arguably he was better known as a regular at the Greek House, a gyro place run by a Greek family which sold a gyro, French fries, and salad for less than five dollars. My dad was beloved there, as he was in many places, because he gave people the feeling that he liked them and was interested in what they had to say, and he gave people this feeling because he did like them and was interested in what they had to say.

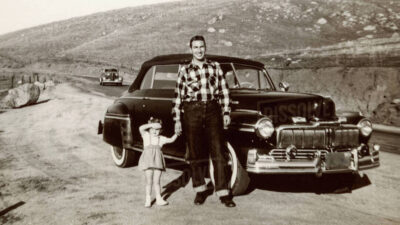

My father had a Ph.D. in applied mathematics, though it had been obtained in a school of geosciences, and so he had been required at some point to acquire competence in geology and maybe something else. He had grown up in a moshav, a collective-farming village, in Israel. The few photographs of him as a child are of him feeding chickens; of him proud alongside a large dog; of him seated in front of an open book with his parents beside him. His mother’s name was Rivka, and she died before I was born. When one of my partner’s sons saw a photo of her, in black-and-white, he thought that it was a picture of me.

Although my dad didn’t say much about his childhood, he did speak, more than once and with admiration, about a donkey from his childhood, named Chamornicus, that was very stubborn. The name, which is old-fashioned slang, translates, approximately, to “my beloved donkey,” but my dad used it when someone was being intransigent. My dad admired stubbornness, especially of the unproductive kind. He once took my brother on a four-week trip to China and Japan. My dad had work conferences to attend. My brother was sixteen or so at the time. My dad took my brother to a bridge that Marco Polo had crossed and said something to the effect of “Isn’t it amazing to think that Marco Polo crossed this same bridge?” And my brother said, “What do I care?” My dad was amused and impressed. My dad also cited with great pride my brother’s insistence on eating at McDonald’s or Shakey’s Pizza while they were in Japan. “He stuck with his guns,” he said, with his characteristic mild mangling of cliché. My dad had a gift for being amused, and for liking people. He was particularly proud of saying, of the anti-immigrant, anti-N.E.A. politician Pat Robertson, “He doesn’t like me, but I like him.” And even when he genuinely disliked, or even hated, people, he enjoyed coming up with nicknames for them. I learned the names of dictators through my parents’ discussions of people nicknamed Mussolini, Idi Amin, and Ceauşescu. He had gentler nicknames for my friends: the Huguenot, Pennsylvania Dutch, and, for a friend with a Greek dad, Kazantzakis.

I said that I was never involved in the household arguments, but I do remember one fight with my dad. He told me a story about something he’d done that day, and I was appalled. He wouldn’t tell a student of his what a herring was. It was a problem on an exam, about herring and water currents. The course was in fluid dynamics. Many of my father’s students came from China. Their English was excellent. But apparently this particular student was unfamiliar with the word “herring.” A deceptive word: it looks like a gerund but isn’t.

My father, who learned English as an adult and would put a little “x” in our home dictionary next to any word he had looked up, and whose work answering-machine message promised to return calls “as soon as feasible,” was, at the time of the herring incident, unfamiliar with the word “cheesy,” having recently asked me to define it for him. He was also accustomed to having students complain about his accent in their teaching evaluations. All that, and still my dad expressed no sympathy for this student. “It’s part of the exam,” my father said that he told the student, as if the line were in the penultimate scene of “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.” My dad had a weakness for narrating moments in which, as he saw it, he dared to speak the truth. One of his favorite films was “High Noon”; this paired well with another favorite of his, “Rashomon.” In one, there’s good and evil; in the other, a tangle of both that can never be unraveled.

I now see that he must have doubted himself in this herring incident, though. Otherwise, why was he telling me the story? I said—with the moral confidence of youth—that he should have told the student what a herring was, that it was an exam on fluid dynamics, not on fish. And I told him that I thought what he had done was mean. We had a pretty long argument about it. But my father stuck with his guns. He said, “When you go through life, you’ll understand that, if you don’t know what a herring is, people don’t tell you. You have to know it yourself.”

I should say that I have, through the years, received notes now and again from students who loved my father. One woman wrote me that his encouragement saved her career when she was thinking of giving up. Some of his students were Chinese dissidents, one had been a journalist, and my dad had helped these students get visas to come over. Shortly after my father died, a student of his from Brazil invited us to his home for dinner. He wanted to tell us how much my father had meant to him. What I really remember about that dinner was the man telling my mother and me that it was difficult for his wife to live in Norman, because in Norman no one tells you that you’re beautiful. “Not at the grocery store. Not at the hardware store. Not on the street. Nowhere! So that is hard for her,” he concluded.

Students complained not only about my dad’s Tzvinglish but also about his handwriting. His accent was very heavy in part because he couldn’t hear well, so his speech was more like what he had read than like what he had heard. But his accent could have been managed if he had had decent handwriting. He was a lefty, from an era before lefties were celebrated, and maybe this had something to do with his terrible handwriting. When he wrote on a notepad, he pressed down with his ballpoint pen so hard that you could see the imprint clearly even several pages beneath, and I often stared at those indentations, which for me had the mesmerizing power of hieroglyphs. Maybe this was what he didn’t want to, or couldn’t, translate for his students—something of making your way in the world when you are, by nature, not really the kind of person who makes his way in the world. Maybe the herring was a red herring. When I went to college, I always praised my foreign grad-student T.A.s to the moon and back.

One fight I remember, because my father did not enjoy it, was about what kind of car he should get when the old one broke down. For years, he drove an enormous used beige Chevy Caprice Classic, which fit all of us plus relatives for long road trips. My dad wanted to replace it with a Jeep with no doors. He had always, he said, wanted a Jeep with no doors. We got a Subaru station wagon.

At about 7 P.M. or so, most nights, I would hear my father pull into the driveway with the station wagon that he wished were a Jeep with no doors. It would then be about forty-five minutes before he entered the house. What was he doing out there? He said that he was organizing. He took seriously all the dials and indicators in the car—the mileage, the warnings, the details of the owner’s manual. He was often going through his hard-shelled Samsonite briefcase again as well.

But also forty-five minutes was, I think, his atom of time, the span of shortest possible duration. It took forty-five minutes to brush and floss his teeth. Forty-five minutes to shave. And forty-five minutes, minimum, to bathe. Forty-five minutes between saying, “I’m almost ready to go,” and going. He, and therefore we, were often late.

These forty-five-minute intervals were because, I think, he did everything while thinking about something else. He lived inside a series of dreams, and each dream could admit only one pedestrian task into its landscape. He often spoke of the life of the mind. He wished for my brother and me that we could enjoy a life of the mind. But, as with many phrases, I think my dad used “the life of the mind” in his own way. He never, for example, urged us to read Foucault, or Socrates, or, really, any books. Those forty-five-minute blocks of daydreams were, I think, closer to what he meant by the life of the mind. They were about idly turning over this or that, or maybe also about imagining yourself as Marco Polo. They were about enjoying being alone, and in your thoughts. That’ll slow you down.

It also took my dad a long time to fall asleep. He managed this by watching reruns of detective shows that came on late at night. He sat in a dining-room chair, close to the television in the living room, not while reclining on his three or four or five pillows in bed. I would sleep on the sofa in the living room, rather than in my own bed, because I didn’t like going to sleep in my room alone. My dad particularly loved “Columbo,” with Peter Falk. Also, a show with a large balding man called Cannon. And “The Rockford Files,” with James Garner. Garner was from Norman. It was known that he was related to my elementary-school principal, Dr. Bumgarner. He was so beloved, a dream of a man—both the actor and the principal. Later, when I was older, there was a new show, “Crazy Like a Fox,” that would come on before the reruns. It starred a father-and-son detective team: the dad was kooky and couldn’t be restrained; the son was practical. Together, they could solve anything. Sometimes I slept through the shows, dimly registering their high-volume presence. At other times I watched them, but while lying down. It was essential that I fall asleep before “The Twilight Zone” reruns came on, because a whole night of sleep would be ruined if I accidentally saw an episode in which there was a fourth dimension in a closet, or a character who discovered that he could pause time.

Until I was at least ten, my dad helped me fall asleep every night. He sang lullabies about boats going out to sea and never returning. He told stories, one of which was about an extremely tiny child, small enough to fit into a soda bottle, and one day, when a wolf comes and eats up all the other normal-sized siblings, the tiny sibling is there to tell the mother what happened, so that she can cut open the wolf’s stomach and retrieve her children, and they then all have the tiniest child to thank for their survival. My daughter is familiar with this story through years of being indoctrinated about the special powers of littleness.

I’m now as old as my dad was when he was a dad, staying up, transitioning into restfulness by watching those shows. Why was my dreamy dad such a fan of detective shows? The only other shows I remember him liking were political-argument shows, “Jeeves and Wooster,” and, for some reason that I have yet to unpack, “The Jewel in the Crown.” Was it because those detectives shrugged into dangerous situations coolly? Because they always said the right thing? Ultimately, they were men of action. They could easily have handled a Jeep with no doors. Maybe they were the ideal avatars for a man devoted to the life of the mind. Not that the shows were a consolation prize for having “no life.” It wasn’t like that. The life of the mind wasn’t no life—it was life. And great battlefields were plentiful. When my brother had a mild conflict with his high-school calculus teacher over a midterm grade, my dad gave him Churchill’s speech about fighting on the beaches and never surrendering. If I had the urge to step back from a just conflict, my dad would remind me that Chamberlain had a choice between war and shame, and that he chose shame but got war later. If you heard my dad humming something, it was probably the “Toreador Song,” by Bizet, or Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.”

I remember a battle he assisted me with. One day, when my brother brought home a soccer trophy, I started to cry. I had never won anything. (If only I had spent my childhood crying less and fighting more!) When the fifth-grade track meet came around, I was set to compete in the one event that had only four competitors—the unpopular distance event. The distance was half a mile. If I could run faster than even one of the other girls, I would get a ribbon, which was at least atmospherically related to a trophy.

Tzvi did something classic in one way but very unlike himself in another. He did something practical. The month before the track meet, he took me out to our school track several nights a week. I ran in a button-up shirt, I now remember, one that was white with blue stripes. Four laps around the track was half a mile. He timed me, and he shouted at me.

During the race, when, on the third lap, I passed a girl whose name I won’t mention to protect her from the indignity of it, she began to cry. To be passed by me was much worse than just coming in last. But my dad had no sympathy for her. The way he saw it, I had shown the world; I had never surrendered. I guess what I’m saying is that some ways of being nice came easily to my father, and other ways were difficult for him, even as, for someone else, it would be a whole other set of things that were easy, that were difficult. When he trained me for that meet, he had done something, for me, that for him was difficult. He had not been forty-five minutes late.

We rarely ate dinner together as a family. My mom doled out to each of us the food that we wanted, at the hour that we wanted it. Chopped-tomato-cucumber-red-onion salads for my father. Plain couscous with butter for me. An argument with my brother about ordering takeout. I believe my mom ate whatever was left over, that no one else wanted. Years later, without quite deciding to, I assumed a similar role. In that role, I nicknamed myself the Invisible Dishrag. Being a dishrag extends beyond cooking, of course. Sometimes I would find myself deeply bothered and resentful about my dishrag role. But most of the time I found myself thinking, perhaps smugly, Well, I’m capable. My dad often talked about how intelligent my mother was. To be a dishrag was not to be Jeannie from “I Dream of Jeannie” (though I loved her, too) but more like Samantha, from “Bewitched.” Samantha was powerful—she could, for example, teleport by wiggling her nose—but she kept her power under wraps out of respect for the man in her life, a guy named Darrin. That I watched so much television during childhood, wasting away like that, I also somehow have become O.K. with. Though it has left me unable to watch any television at all now, when television has supposedly become so good.

There was one meal that my family did eat together. That was the Passover meal, which we usually shared with the Scottish Jewish Orthodox family who lived on the other side of town, the Levines. To this day, my brother and I still call roasted potatoes Levine potatoes. What I remember best about those Seders was how my dad and Martin Levine, a dentist, were capable of long discussions about almost any line of the Haggadah. They debated the meaning of the line “My father was a wandering Aramaean.” Where and when had they got this knowledge? My dad came from a very secular family, but, in the Israeli Army, he had won some sort of contest in Bible knowledge. (This is also true of Bertie Wooster.) That my father had been in the Army—that fact felt to me like fiction, though we had his old Army water bottle under the kitchen sink. For some reason, the inessential learnedness of those Seder meals impressed me as something that I could never accomplish but which resided in the realms where true worth lay.

When my dad’s father died, he didn’t tell me. My mom told me that my grandfather had died, and that was why my dad was away, but that he would be home soon. When my dad returned, he attended our local Hillel each Friday, sometimes with me, to say the Mourner’s Kaddish. Often, there weren’t the required ten men present to have a “real” service, with the Kaddish, and this frustrated my father: he had come for the Kaddish. As a child, I didn’t count among the ten—maybe also as a female. I remember that my father argued otherwise.

That Kaddish year gave me a narrow but real peek into my dad’s childhood. I knew that my grandfather put a sugar cube into his mouth when he drank tea, and that he told my dad he wouldn’t understand the movie “Rashomon” until he was older. I think Tzvi said little to me about his own childhood because he wanted to let me have my childhood, and not crowd it out with the inner lives and melancholies and anxieties of adults. He did say to me once, “Your mother and I did one thing right. We made sure that you and your brother got to be children for a long time.” What he felt worst about was that the family had to move so much when my brother was young; after I started first grade, we stayed in place for more than ten years. I’ve come to think that maybe my childhood was happy mostly because it was childhood. When I moved in with my partner and his children, and later when I had a child, my own childhood returned to me. I believe that children arrive with their own life of the mind, and that to the extent that they get to spend time in that world which they themselves have invented—that’s pretty good. Much of the rest is roulette.

The summer after my dad died, I found myself studying at a women’s yeshiva in Jerusalem—I assume because I thought I’d learn some of the Biblical knowledge mysteriously held by my father. My family thought I was insane. I may as well have been studying with Scientologists, as far as they were concerned. Most of the young women there had, well, backstories. One was a professional dancer who had been in a car crash and broken her back. Another was the daughter of a psychiatrist who had been shot by one of his patients. Another was just a very tall and very slim woman who we all knew was “from Oxford.” One of the rabbis who instructed us had blue eyes and had been a d.j. and a ski instructor living in Berkeley before becoming religious. He told us a long story in class one day about how, through a series of kooky chance encounters, his son’s congenital heart malformation was found and immediately operated on—and that this was because Hashem was watching out for him. At that point, I decided that my dad would have sided with the rest of my family, and wanted me out of there. My dad’s voice has often been with me in this way, generally amused, occasionally in the mood for a fight.

One afternoon, toward the end of my last year of high school, I found pages from a magazine torn out and taped to my door. The pages were titled “Messages from My Father,” and they were by Calvin Trillin, in the June 20th, 1994, issue of The New Yorker. The reason we had a New Yorker subscription at all was that it was advertised on one of those Sunday mornings when my dad watched the “fighting shows” at full volume, and I had said that maybe we should get a subscription, and he had said, “I don’t have time to read it, but how about you read it, and you tell me if there’s something in there I should read.” The day that my dad taped the Trillin piece to my door, he told me that I should one day write something like that about him. Ha-ha. Four months later, my father had a heart attack and died, at the age of fifty-three. I didn’t write that essay. I didn’t know enough. I barely even knew that my father was gone. I was not many weeks into my first year of college, and a substantial part of me thought, I’ll see him when I go back to Oklahoma. I had several dreams in which he was sitting in a booth at a diner. When my Spanish teacher learned, through some conversation exercise, that my father was a meteorologist, she told me that she had always wanted to understand how wind chill was calculated, and she asked me to ask my dad about that. I told her I would.

Original article here

In the run-up to marriage, many couples, particularly those of a more progressive bent, will encounter a problem: What is to be done about the last name?

In the run-up to marriage, many couples, particularly those of a more progressive bent, will encounter a problem: What is to be done about the last name? In a forthcoming study, Kristin Kelley, a doctoral student working with Powell, presented people with a series of hypothetical couples that had made different choices about their last name, and gauged the subjects’ reactions. She found that a woman’s keeping her last name or choosing to hyphenate changes how others view her relationship. “It increases the likelihood that others will think of the man as less dominant—as weaker in the household,” Powell says. “With any nontraditional name choice, the man’s status went down.” The social stigma a man would experience for changing his own last name at marriage, Powell told me, would likely be even greater.

In a forthcoming study, Kristin Kelley, a doctoral student working with Powell, presented people with a series of hypothetical couples that had made different choices about their last name, and gauged the subjects’ reactions. She found that a woman’s keeping her last name or choosing to hyphenate changes how others view her relationship. “It increases the likelihood that others will think of the man as less dominant—as weaker in the household,” Powell says. “With any nontraditional name choice, the man’s status went down.” The social stigma a man would experience for changing his own last name at marriage, Powell told me, would likely be even greater.

That’s what legendary Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk, teacher, and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh (October 11, 1926–January 22, 2022) explored in How to Love — a slim, simply worded collection of his immeasurably wise insights on the most complex and most rewarding human potentiality.

That’s what legendary Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk, teacher, and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh (October 11, 1926–January 22, 2022) explored in How to Love — a slim, simply worded collection of his immeasurably wise insights on the most complex and most rewarding human potentiality. And yet because love is a learned “dynamic interaction,” we form our patterns of understanding — and misunderstanding — early in life, by osmosis and imitation rather than conscious creation. Echoing what Western developmental psychology knows about the role of “positivity resonance” in learning love, Nhat Hanh writes:

And yet because love is a learned “dynamic interaction,” we form our patterns of understanding — and misunderstanding — early in life, by osmosis and imitation rather than conscious creation. Echoing what Western developmental psychology knows about the role of “positivity resonance” in learning love, Nhat Hanh writes:

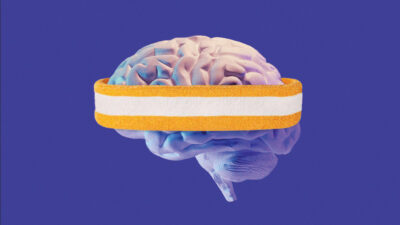

In 2007, a group of researchers began testing a concept that seems, at first blush, as if it would never need testing: whether more happiness is always better than less. The researchers asked college students to rate their feelings on a scale from “unhappy” to “very happy” and compared the results with academic (GPA, missed classes) and social (number of close friends, time spent dating) outcomes. Though the “very happy” participants had the best social lives, they performed worse in school than those who were merely “happy.”

In 2007, a group of researchers began testing a concept that seems, at first blush, as if it would never need testing: whether more happiness is always better than less. The researchers asked college students to rate their feelings on a scale from “unhappy” to “very happy” and compared the results with academic (GPA, missed classes) and social (number of close friends, time spent dating) outcomes. Though the “very happy” participants had the best social lives, they performed worse in school than those who were merely “happy.” Life has sped up. A never-ending stream of stimuli is vying for your attention every minute of the day. Some of it is fabulous and some of it is time wasting.

Life has sped up. A never-ending stream of stimuli is vying for your attention every minute of the day. Some of it is fabulous and some of it is time wasting. In a world where it is almost impossible to lose contact with friends, thanks to the likes of social media, this regret may seem irrelevant. You can send someone a text to say you’re thinking of them, comment on their Facebook feed or Instagram photo, or chat via Messenger. But how long is it since you’ve really connected with these people in real life? How long since you’ve laughed together, cried together, eaten together or just hung out?

In a world where it is almost impossible to lose contact with friends, thanks to the likes of social media, this regret may seem irrelevant. You can send someone a text to say you’re thinking of them, comment on their Facebook feed or Instagram photo, or chat via Messenger. But how long is it since you’ve really connected with these people in real life? How long since you’ve laughed together, cried together, eaten together or just hung out?

I believe in angels. I feel their presence in my life every hour, minute and second, I know they are with me, with us, but how? From a rational point of view, it is probably impossible to explain their existence, however I can say that they are part of my experience.

I believe in angels. I feel their presence in my life every hour, minute and second, I know they are with me, with us, but how? From a rational point of view, it is probably impossible to explain their existence, however I can say that they are part of my experience.

There’s a conversation you’re avoiding. It feels important, the stakes are high, there are strong feelings involved and you are putting it off: “The time isn’t right”; “I can’t find the words”; “I don’t want to get emotional”.

There’s a conversation you’re avoiding. It feels important, the stakes are high, there are strong feelings involved and you are putting it off: “The time isn’t right”; “I can’t find the words”; “I don’t want to get emotional”.