Most American yards don’t reflect their ecological condition. The plants need to be treated with fertilizer because the soil’s not right. They want water the weather doesn’t provide. Wildlife disappears because they no longer have food to eat. All this creates more labor for homeowners, the humans in this ecosystem, because they’re working against nature instead of with it.

“A garden that’s planted purely by aesthetic decisions is like a car with no engine,” says Larry Weaner, founder and principal of Larry Weaner Landscape Associates in Glenside, Pennsylvania. “It may look beautiful, the stereo works great, but you’re going to have to push it up the hill.”

A yard should have an engine. You just have to grow plants adapted to your landscape and work with wildlife instead of trying to control it, which will foster diversity and stability in your local ecosystem. More than ornaments, plants have functions in a regenerative system. When you engage the natural landscape, you reconnect to your region and your ecosystem, and create a piece of land that reflects its place. Here’s how.

Step 1: Understand Your Land

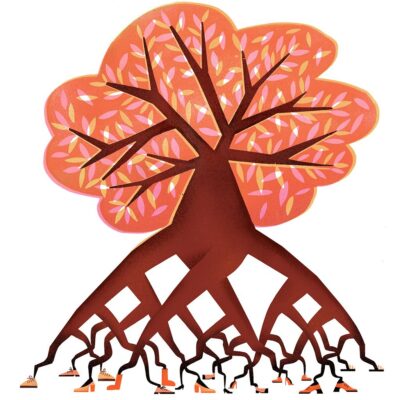

The great likelihood is that you’re going to be adapting to the conditions you already have. Those conditions might not appear to be “optimal” in the traditional horticultural sense. But plants grow in the wild without fertilizer. Survivors adapt, learning to love even marginal soil. They also forge relationships with other plants, animals, and the microbiology of the soil. These relationships become the foundation of a sustainable and resilient landscape.

The great likelihood is that you’re going to be adapting to the conditions you already have. Those conditions might not appear to be “optimal” in the traditional horticultural sense. But plants grow in the wild without fertilizer. Survivors adapt, learning to love even marginal soil. They also forge relationships with other plants, animals, and the microbiology of the soil. These relationships become the foundation of a sustainable and resilient landscape.

Get to know your climate

Temperatures, average rainfall. Look up where you fall on the USDA’s Plant Hardiness Zones and Koppen Climate Classification maps. Hike in nature preserves near your house, visit demonstration gardens, go on home tours, walks, and lectures offered by your area’s native plant society to learn about the plants of your region. Note which plants you like how do they grow? On a forest floor? In a meadow? What do they grow with? Or do they grow alone? You can learn more about soil types and climates that plants prefer by cross-referencing their location with specialty maps on The Biota of North America Program’s website: bonap.org.

Notice where you admire the larger structure of the landscape. It could be light falling through trees, or maybe a sense of spaciousness. Understand the aspects of nature that you respond to viscerally for design inspiration.

Get to know your yard

Watch the light exposure morning, midday, and evening, and consider how it changes, especially during the spring and fall when the sun angle shifts quickly. What direction does your house face? Do you have walls, fences, or trees that impact light or airflow? Are you on a hill? How is the water moving through your property? Hold a scoop of soil in your hand to see how it holds moisture. Get a soil test—not to change it, but to know what you’re working with. Take pictures, draw maps describing the microclimates created by sun, shade, water, and soil. These will be your planting zones, and they’ll help you figure out what to plant and where to plant it.

Step 2: Design Your Space

Now that you’ve observed, ask…What plants will thrive in my yard? In other words, what does nature want? And what do I want? Where these desires meet will be the foundation of your design.

Now that you’ve observed, ask…What plants will thrive in my yard? In other words, what does nature want? And what do I want? Where these desires meet will be the foundation of your design.

Is it a priority to have an extremely low-maintenance landscape? Keep your selections simple. Don’t bring in too many plants with different care requirements. (Always factor maintenance into design.) If floods are an issue in your area, think trees or a rain garden full of evergreen plants that like having wet feet. Do you want to attract butterflies or birds? Consider what canopy layers you have in your yard— groundcover, small shrubs, large shrubs, small trees, large trees, recommends Susie Peterson, backyard habitat certification program manager for Columbia Land Trust and the Portland Audubon Society. “Different birds, different bees, different kinds of wildlife, live at different levels.”

Choose your plants

Long-term, native perennials will create a more stable, low-maintenance landscape. While native plants are essential to local wildlife— especially the keystone genera (which make up only 5 percent of the area’s native species but produce 75 percent of the food) Ninety percent of insects only eat the leaves of plants with which they co-evolved. They, in turn, feed the birds and other animals. The more diverse an ecosystem is, the more species it contains, the more stable and productive it is,” says ecology author and University of Delaware professor Doug Tallamy. “The single biggest thing you can do to make an impact on local habitat and rainwater absorption is planting trees,” says Peterson.

Buy plants from a good nursery

Native plants are also known as “local eco-types.” A beech tree grown in Florida won’t do well in a Pennsylvania winter even if it’s the same species, so ask nurseries about the provenance of the plants.

Once you find a good nursery that takes eco-type into account, tell them about your site, and they can help you select good choices for your yard. You can also find local plant sales through native plant societies and conservation districts. If you research how plants propagate, nature will donate to the cause.

Step 3: Prepare the Site and Install

Remove invasive plants

Check in with your soil conservation district to get a list of the invasive species of your area. Odds are, you have at least one invasive species in your yard, and its offspring will rapidly spread to your local natural areas, reducing their ability to support wildlife. Handpulling to remove is best. But if it’s an established woody plant, you may need professional help. Tree companies can grind out the roots. Or you can rent a grinder and do it yourself.

Your soil and water conservation district can connect you with contractors, and sometimes they offer grants to help cover the cost.

Start small

Choose one of the micro regions you found in your yard and clear a bed no larger than 150 square feet. See how much you can create before you take on more. “Your neighbors are going to appreciate something that’s done well,” says Scott Woodbury manager of Whitmire Wildflower Garden in Gray Summit, Missouri. “But nobody wants something that became a weed patch because you bit off more than you could chew.”

Don’t amend the soil

“There are plants—beautiful ones—that are adapted to pretty much every soil type,” says Larry Weaner, “If you make the soil perfectly rich, you can grow pretty much anything you want, but the weeds are going to grow beautifully. I’d rather work with the soil that’s there and the plants that are adapted to that soil. They’ll form a denser, thicker, weed-suppressor cover more quickly.”

Cover the ground

“Nature abhors a vacuum,” says Claudia West, coauthor of Planting in a Post-Wild World and principal at Phyto Studio in Arlington, Virginia. “Bare soil, even if it’s covered with mulch, is not stable or persistent. The first step to making a planting that needs less maintenance is to fill every inch of a garden with desirable plants as densely as possible.”

Landscape plugs—small seedlings sold in flats—spaced at 10 to 12 inches on center or growing from seed are the most cost-effective ways to do this. Depending on the planting, you may need to mulch around the plants during the establishment phase to suppress weeds.

Step 4: Maintain It

Give it time to become established

The establishment phase is about two years. “In the early stages, you’re sorting out what you’re going to allow to become dominant,” says Weaner. So think of those first few years as a continuation of the design process. You help your plants beat out the weeds, but you also help them find balance with one another.

If one grows slowly compared to another, you may need to cut the faster plant back the first few years so the other can survive.

Long-term

Instead of weekly maintenance, you’ll transition to seasonal projects like deadheading a shrub for more blooms or cutting back perennial grasses—practices to help the plants be the best versions of themselves. Weeds will still arrive from time to time. Spot-treat by cutting down at the base. Shaded by groundcover, they won’t be able to compete with your plants.

Mow your lawn high

Learn the appropriate mowing height for your grass—it’s different depending on the varietal. And never remove more than one-third of the blade. Cutting low decreases the plant’s rooting, which inhibits water and nutrient uptake. Clippings recycle as much as 50 percent of the nitrogen that grass needs back into the soil. If you mow a quarter acre or less, consider switching to a reel mower. Gas lawn mowers are statistically 25 times more polluting than cars. For an acre or less, try an electric mower with a rechargeable battery.

Water less

Grass needs one inch of water per week during the growing season. East of the Mississippi, as long as you don’t mind dormancy during a drought—meaning, it may look crispy and brown, depending on the type, but still be very much alive — you don’t need to irrigate your lawn. Most varieties of grass will tolerate drought stress better than people realize.

Organize it

From Claudia West: Make your yard look even better with frames, which can be as simple as a neat and tidy fence, a curb, a mowed edge with a couple feet of turf or clipped hedges. Maintaining the edges, adding a bench—these are cues of care that indicate the planting is something you intended to create.

Make it pretty!

Pay attention to what blooms when, and factor seasonal shifts of color into your design. Says West: “You probably remember in fall when entire fields bloom in goldenrod, a sea of yellow. Or spring when you walk near a floodplain and see millions of Virginia bluebells. What if 20 percent of your planting erupted in purple, pink, white, or orange? That’s a spectacular event.”

Designs are more successful when we choose a language based on an ancient perception of beauty.

Step 5: Support It

Watch how the landscape evolves. “Don’t be discouraged if some of the plants in your palette don’t do well, even though you did the research,” says Max Kanter, cofounder of Saturate, an ecologically minded gardening company in Los Angeles. Some might not be placed quite right, while others will thrive in ways you didn’t expect. “Start to practice the idea that the garden is a process,” he says. It’s not an installation or a transaction; it’s a relationship.

Watch how the landscape evolves. “Don’t be discouraged if some of the plants in your palette don’t do well, even though you did the research,” says Max Kanter, cofounder of Saturate, an ecologically minded gardening company in Los Angeles. Some might not be placed quite right, while others will thrive in ways you didn’t expect. “Start to practice the idea that the garden is a process,” he says. It’s not an installation or a transaction; it’s a relationship.

You’re not just giving your yard back to nature. You’re sharing it, which in a way, is giving yourself back to nature, too.

Original article here