In February 2015, a Scottish woman uploaded a photograph of a dress to the internet. Within 48 hours the blurry snapshot had gone viral, provoking spirited debate around the world. The disagreement centred on the dress’s colour: some people were convinced it was blue and black while others were adamant it was white and gold.

In February 2015, a Scottish woman uploaded a photograph of a dress to the internet. Within 48 hours the blurry snapshot had gone viral, provoking spirited debate around the world. The disagreement centred on the dress’s colour: some people were convinced it was blue and black while others were adamant it was white and gold.

Everyone, it seemed, was incredulous. People couldn’t understand how, faced with exactly the same photograph of exactly the same dress, they could reach such different and firmly held conclusions about its appearance. The confusion was grounded in a fundamental misunderstanding about colour – one that, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, shows little sign of disappearing.

For a long time, people believed that colours were objective, physical properties of objects or of the light that bounced off them. Even today, science teachers regale their students with stories about Isaac Newton and his prism experiment, telling them how different wavelengths of light produce the rainbow of hues around us.

But this theory isn’t really true. Different wavelengths of light do exist independently of us but they only become colours inside our bodies. Colour is ultimately a neurological process whereby photons are detected by light-sensitive cells in our eyes, transformed into electrical signals and sent to our brain, where, in a series of complex calculations, our visual cortex converts them into “colour”.

Most experts now agree that colour, as commonly understood, doesn’t inhabit the physical world at all but exists in the eyes or minds of its beholders. They argue that if a tree fell in a forest and no one was there to see it, its leaves would be colourless – and so would everything else. To put it another way: there is no such thing as colour; there are only the people who perceive it.

This is why no two people will ever see exactly the same colours. Every person’s visual system is unique and so, therefore, are their perceptions. About 8% of men are colour-blind and see fewer colours than everyone else; a small number of lucky women might, thanks to a genetic duplication on the X chromosome, be able to distinguish many more than the rest of us.

Animals inhabit very different chromatic worlds too. Most mammals are red-green colour-blind; bulls might be famous for their hatred of red capes, but the colour itself is invisible to them – they are actually enraged by the fabric’s movements. By contrast, most reptiles, amphibians, insects and birds perceive more colours than us. Bees see ultraviolet light, discerning elaborate patterns in flowers that we cannot perceive, while snakes see infrared radiation, detecting the warm bodies of prey from a distance.

People generally name only the colours they consider socially or culturally important

“Colour,” Umberto Eco once said, “is not an easy matter.” It is indeed elusive and illusive. Pretty much everything we take to be self-evident about it really isn’t self-evident at all. Scientists have shown that the sky isn’t blue, the sun isn’t yellow, snow isn’t white, black isn’t dark and darkness isn’t black.

One cause of the problem – or perhaps its symptom – is language. In English we divide colour space into 11 basic terms – black, white, red, yellow, green, blue, purple, brown, grey, orange and pink – but other languages do things differently. Many don’t have words for pink, brown and yellow, and some use one word for both green and blue. The Tiv people in west Africa use only three basic colour terms (black, white, red), and at least one Indigenous community has no specific words for any colours, only “light” and “dark”.

The vocabulary of these languages isn’t dictated by the prismatic spectrum but, once again, by what is happening inside their speakers’ heads. People generally name only the colours they consider socially or culturally important. The Aztecs, who were enthusiastic farmers, used more than a dozen words for green; the Mursi cattleherders of Ethiopia have 11 colour terms for cows, and none for anything else.

These differences might even influence the colours they see. Debates about linguistic relativity – the extent to which our words shape our thoughts and perceptions – have been rumbling on for decades, and while many scholars have overstated the case for it, some have found persuasive evidence that if you don’t, say, have a word for blue, you will probably find it harder to distinguish.

The meanings of colour are no less socially constructed, which is why a single colour can mean completely different things in different places and at different times. In the west white is the colour of light, life and purity, but in parts of Asia it is the colour of death. In America red is conservative and blue progressive, while in Europe it’s the other way around. Many people today think of blue as masculine and pink as feminine, but only a hundred years ago baby boys were dressed in pink and girls in blue.

When all of this is taken together – the subjective nature of visual perception, the complicating influence of language, the role that social life and cultural traditions play in filtering our understandings of colour – it becomes really rather difficult to reach a conclusion different from that of the 18th-century philosopher David Hume: that, in the end, colour is “merely a phantasm of the senses”.

The ancient Egyptian term for “colour” was iwn – a word that also meant “skin”, “nature”, “character” and “being”, and was represented in part by a hieroglyph of human hair. To the Egyptians, colours were like people – full of life, energy, power and personality. We now understand just how completely the two are entangled. That’s because every hue we see around us is actually manufactured within us – in the same grey matter that forms language, stores memories, stokes emotions, shapes thoughts and gives rise to consciousness. Colour is, if you’ll pardon the pun, a pigment of our imaginations.

Original article here

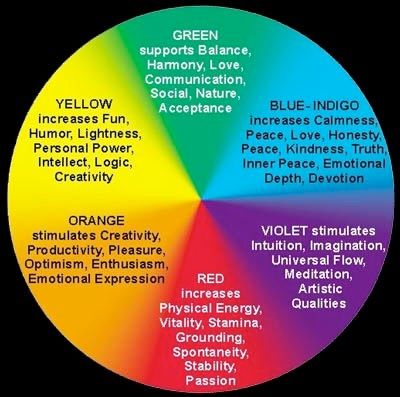

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be able to use colors as a way to make your life healthier? The truth is, you can. Dr. Alexander Wunsch, who is based in Germany, is a world-class expert in the use of light as a therapeutic healing agent, and is a human treasure trove of information on a topic that very few people understand.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be able to use colors as a way to make your life healthier? The truth is, you can. Dr. Alexander Wunsch, who is based in Germany, is a world-class expert in the use of light as a therapeutic healing agent, and is a human treasure trove of information on a topic that very few people understand. You can implement colored light therapy either by shining light through a colored filter, or by wearing colored glasses, so that the light striking your retina is of a particular color frequency.

You can implement colored light therapy either by shining light through a colored filter, or by wearing colored glasses, so that the light striking your retina is of a particular color frequency.

Our awareness of this Source of Unconditional Love is blocked on a personal, as well as cultural level. This has occurred for a number of reasons, the primary one being the Creation Myth that is known by nearly everyone in our culture whether they choose to subscribe to it or not. Put simply, we are the children of a couple that blew it (it was her fault) and we have been cast out of the Garden, separated from God, to suffer forever in the world of Duality.

Our awareness of this Source of Unconditional Love is blocked on a personal, as well as cultural level. This has occurred for a number of reasons, the primary one being the Creation Myth that is known by nearly everyone in our culture whether they choose to subscribe to it or not. Put simply, we are the children of a couple that blew it (it was her fault) and we have been cast out of the Garden, separated from God, to suffer forever in the world of Duality. Technology is not the only factor that benefits from this process – the individual healing process is also speeding up. Issues that previously may have taken years to get through are now being healed within a matter of months, even weeks. It is as if time has speeded up – or more appropriately, our beliefs have expanded to include a simple truth: we can heal ourselves, and so the process is not altered by false beliefs any longer.

Technology is not the only factor that benefits from this process – the individual healing process is also speeding up. Issues that previously may have taken years to get through are now being healed within a matter of months, even weeks. It is as if time has speeded up – or more appropriately, our beliefs have expanded to include a simple truth: we can heal ourselves, and so the process is not altered by false beliefs any longer.