About the Artist:

I was born on 12/24/1988 in Russia. I’ve been painting for as long as I can remember. I always knew that I would be an artist, only the direction changed: at one time I wanted to be an architect, then a sculptor, a portrait painter, an animator. As a result, I received higher education as a shoe designer and even managed to work for three years in this specialty.

I was born on 12/24/1988 in Russia. I’ve been painting for as long as I can remember. I always knew that I would be an artist, only the direction changed: at one time I wanted to be an architect, then a sculptor, a portrait painter, an animator. As a result, I received higher education as a shoe designer and even managed to work for three years in this specialty.

My main theme is nature! I have always been surrounded by trees, fields and forests. Watch the dawn, inhale the smell of wet grass, listen to the sound of the wind. This is real happiness, and this happiness is available to everyone! We can all look at the sky, sit by a tree, even if we live in a city.

In nature there is nothing absolutely identical: each branch, each leaf is unique. It is very interesting to look at their curves, and then strive to paint on the sheet. I suffered for a long time, I had false attitudes from art school … for example, that a real artist paints only with oil, acrylic is so … for beginners, or that the tree is not blue at all, and the sky is not green at all. Not!!! Creativity is freedom! I love graphics and sculpture and painting very much. I didn’t “try” to do anything, and therefore I began to paint the way I like. I called my style: “textural-graphic impressionism”.

Why acrylic? Acrylic has several advantages:

- It is a real treasure for those who like to experiment!

- It dries quickly and there are no rules from thin to thick. For me, this is very important. I also studied physics and mathematics, and the order, the sequence of significance. I love that I can paint many coats and not have to wait months for it to dry.

- It darkens and fades! That is why it is not for beginners! You paint the picture after drying, you see another one… it is also flat, but this can be compensated for…

Yes, I am an artist. But I am also a mother. Being a mother is my main job. This is a priority for me, I enjoy every moment with my children while they need me, so I paint when they are sleeping.

I especially like to paint while traveling. When I’m not at home, my quiet morning hours are from 04-09:00, this is my work time and I work.

Find all my social media art links here: https://linktr.ee/anastasiatrusova

Forgiveness is often viewed as the “happily ever after” ending in a story of wrongdoing or injustice. Someone enacts harm, the typical arc goes, but eventually sees the error of their ways and offers a heartfelt apology. “Can you ever forgive me?” Then you, the hurt person, are faced with a choice: Show them mercy — granting yourself peace in the process — or hold a grudge forever. The choice is yours, and it’s one many of us assume starts with remorse and a plea for grace.

Forgiveness is often viewed as the “happily ever after” ending in a story of wrongdoing or injustice. Someone enacts harm, the typical arc goes, but eventually sees the error of their ways and offers a heartfelt apology. “Can you ever forgive me?” Then you, the hurt person, are faced with a choice: Show them mercy — granting yourself peace in the process — or hold a grudge forever. The choice is yours, and it’s one many of us assume starts with remorse and a plea for grace. Enright defines forgiveness as a moral virtue. Moral virtues (like kindness, honesty, and patience) are typically focused on how they benefit others; these are things you do primarily for another person’s sake, regardless of whether or not they have “earned” it.

Enright defines forgiveness as a moral virtue. Moral virtues (like kindness, honesty, and patience) are typically focused on how they benefit others; these are things you do primarily for another person’s sake, regardless of whether or not they have “earned” it. Enright has studied forgiveness extensively. He says his research group at the University of Wisconsin Madison was the first to publish a scientific study on forgiveness, in 1989; in 1993, they became the first to publish a scientific study of forgiveness therapy. Their research has led to the development of a step-by-step process for forgiveness, which can happen in therapy (ideally with someone who is trained in forgiveness therapy), or through a self-guided process using his workbook.

Enright has studied forgiveness extensively. He says his research group at the University of Wisconsin Madison was the first to publish a scientific study on forgiveness, in 1989; in 1993, they became the first to publish a scientific study of forgiveness therapy. Their research has led to the development of a step-by-step process for forgiveness, which can happen in therapy (ideally with someone who is trained in forgiveness therapy), or through a self-guided process using his workbook. Let’s play a game of “would you rather.”

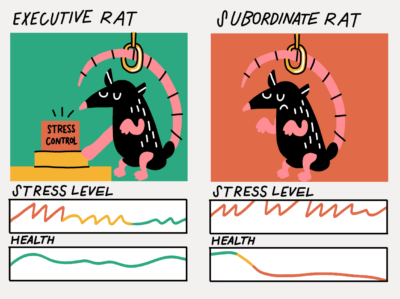

Let’s play a game of “would you rather.” The rat with the lever in its cage is called “the executive rat,” because it has control. It has the power to turn off the electric current flowing through the cage. The rat with no control is called the “subordinate rat.”

The rat with the lever in its cage is called “the executive rat,” because it has control. It has the power to turn off the electric current flowing through the cage. The rat with no control is called the “subordinate rat.” Are you facing the stress of an uncertain future? If so, it helps to focus on what you can control. Sometimes that means bringing the finish line closer by setting goals for today or this week instead of trying to figure out what you’ll do if you lose your job three months from now. Sometimes, it means making a list of 10 ways you can stay connected with friends and choosing the best one to put into action.

Are you facing the stress of an uncertain future? If so, it helps to focus on what you can control. Sometimes that means bringing the finish line closer by setting goals for today or this week instead of trying to figure out what you’ll do if you lose your job three months from now. Sometimes, it means making a list of 10 ways you can stay connected with friends and choosing the best one to put into action. For example, an entrepreneur who feels constantly pressed for time during her nine-hour workday might experiment with doing a 14-hour workday once per week for three weeks. Each of these long workdays is followed by a shortened workday of only six hours. In this case, she is stretching her sense of what’s possible by working longer than what feels comfortable. Then she recovers, taking it easy the next day.

For example, an entrepreneur who feels constantly pressed for time during her nine-hour workday might experiment with doing a 14-hour workday once per week for three weeks. Each of these long workdays is followed by a shortened workday of only six hours. In this case, she is stretching her sense of what’s possible by working longer than what feels comfortable. Then she recovers, taking it easy the next day. The world is full of outsiders: students away at a university far from home, immigrants to a new country, and people who go abroad for work or extended travel. Over the past year, more than 4.4 million American workers quit their jobs in the “Great Resignation,” and many of them became outsiders by joining a different company or moving to a new place, which they perhaps imagined might be friendlier to their personal needs and tastes.

The world is full of outsiders: students away at a university far from home, immigrants to a new country, and people who go abroad for work or extended travel. Over the past year, more than 4.4 million American workers quit their jobs in the “Great Resignation,” and many of them became outsiders by joining a different company or moving to a new place, which they perhaps imagined might be friendlier to their personal needs and tastes.