When the U.S. tried to rid its cities and rural towns of coyotes starting around the 19th century, the effort backfired. While coyote control programs — involving chemical poisons, steel traps and paid bounties — did in fact kill tens of millions of the species, the population only spread further out.

“They responded by taking over the entire continent,” says Peter Alagona, an environmental historian at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Coyotes can now be found in every state except Alaska, as well as in parts of Canada and Central America, and they’ve moved from the fringes of cities to urban backyards.

“You have to admire their grit and adaptability for being able to live in Arctic tundra, in tropical rainforest, in deserts and in places like, you know, the Bronx,” he says.

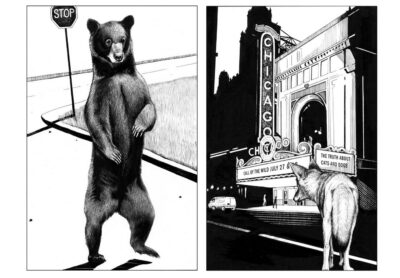

The resiliency of coyotes is recounted in Alagona’s 2022 book, The Accidental Ecosystem, which retraces the land use decisions that have, intentionally or not, allowed some wildlife species to proliferate across the the U.S. even after they’d been deliberately targeted to make way for cities. It’s not just coyotes and commonly sighted critters like squirrels black bears, foxes and even pumas have been spotted wandering the streets of crowded metro areas.

Bloomberg CityLab spoke with Alagona about the ways in which animals have adapted to cities and even thrived there, while urbanites struggled to coexist with them.

Can you help us set up the series of events that led to the so-called “accidental ecosystem” in American cities?

There’s this early phase in which cities get established disproportionately in areas that were really rich and productive biologically, and where prosperous indigenous communities sprouted up. Wildlife gets cleared off the landscape and replaced in many of these growing urban centers with huge numbers of domesticated animals — livestock and animals we often think of today as pets — that were kind of filling the niches that wild animals would have filled.

These domesticated animals then get cleared out by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading to this period from about 1920 to 1950 where there are fewer wild animals living in urban areas, particularly in North America, than really at any time before or since. This is a period in which some of the greatest thinkers about urban life were doing their writing, and almost everybody assumed that cities weren’t going to have animals in them.

These domesticated animals then get cleared out by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading to this period from about 1920 to 1950 where there are fewer wild animals living in urban areas, particularly in North America, than really at any time before or since. This is a period in which some of the greatest thinkers about urban life were doing their writing, and almost everybody assumed that cities weren’t going to have animals in them.

But that gap in time is fascinating because cities, by planting trees, establishing new parks and cleaning up polluted areas — decisions that people made consciously for reasons that had to do with human health, human well-being, the urban environment, real estate values, those sorts of things — were setting the stage for wildlife to come back. The increasing leafiness meant that some creatures that depended on a tree canopy, like Eastern gray squirrels or the many birds that passed through, could return.

But it wasn’t just decisions that were made inside cities that enabled not only small critters but also large mammals and predators to return?

Inside cities, creating new parks from old industrial areas created new spaces for animals to hide out during the day, and then “commute” [further] into the city at night to access resources.

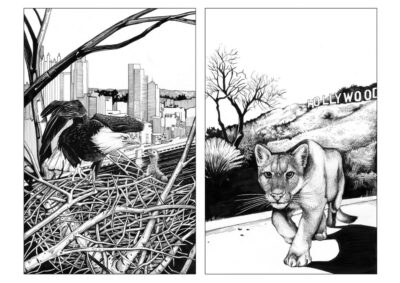

At the wildland urban interface, where you have urban areas and suburbs butting up against large natural areas, you see more of these larger animals like black bears and occasionally even pumas, certainly lots of coyotes. Those are places where animals, again, can take cover during the day, and access resources along the urban fringe in the evening. This is particularly prevalent in areas like north of Los Angeles, where these foothill communities have grown right up to the edge of the national forest.

As the local environment in Pittsburgh recovered from its post-industrial era, raptors like the bald eagle returned. Big cats have always existed on the fringe of Los Angeles, but in 2016, a puma dubbed P-22 made his way into the city. Illustrator: Jane Kim, Ink Dwell Studio/Courtesy of University of California Press

Then there are conservation activities in the outlying areas. On the East Coast and the Midwest, efforts to recover populations of white tail deer — which had declined dramatically during the 19th century, down to 5% of its historic numbers — in rural areas enabled those creatures to then start to colonize areas like suburbs, as suburbs grew much more widely after World War II.

How were animals able to adapt, and even thrive, in habitats that are so different from their natural ones?

It used to be thought that most creatures were fixed in their behaviors, and behavioral change would be really slow, if at all. It’s turned out, though, that quite a few creatures have shown themselves to be more flexible than people ever thought.

You have the urban exploiters, which are at home in cities and often live in cities in great numbers. These include pigeons, rats and some squirrels. Then there are the urban adapters that are not really truly at home in cities, but they come because of the resources, and they have proven pretty adaptable. If you’re driving on the freeway, and see a great blue heron foraging in a drainage ditch, those are urban adapters.

And finally, the urban avoiders are those you almost never see in cities, and when you do, it’s usually because there’s something wrong. They’re either trying to get from one patch of natural habitat to another, or they found themselves there by accident. These are creatures like pumas and wolverines.

So we can see that there are a wide variety of adaptations and evolutionary histories are at play in allowing some creatures to tap this amazing bounty of resources in our cities, while avoiding hazards including night light, chemical pollution and certainly automobiles.

Black bears and raccoons have become great at dumpster diving, and certain animals know when is the best time to come out to avoid humans. Are there concerns about how easily some animals have adapted?

There are an expanding number of these examples of rapid human-induced evolution. There are a handful of entirely new species or subspecies, particularly of insects, that have developed in particular kinds of urban environments. And then there are a wide variety of behavioral adaptations, or even physical adaptations, that seem to have occurred as a result of certain kinds of animals being put under extreme, selective pressures by the changing environments that people create.

But these examples are exceptions, not the rule. And this is very time-dependent: Although there are a small number of creatures that can adapt very quickly, for most others, this would take a long period of time — much longer than it takes for their populations to go extinct. And so the problem is [talking] about this as a solution to the fact that we’re rearranging and degrading ecosystems in ways that make the world a much harder place to live for the vast majority of species out there.

But these examples are exceptions, not the rule. And this is very time-dependent: Although there are a small number of creatures that can adapt very quickly, for most others, this would take a long period of time — much longer than it takes for their populations to go extinct. And so the problem is [talking] about this as a solution to the fact that we’re rearranging and degrading ecosystems in ways that make the world a much harder place to live for the vast majority of species out there.

Humans, meanwhile, have struggled to adapt to the presence of wildlife. Your book describes many attempts to control animal populations, whether it’s to get rid of them or protect them, that haven’t always had the intended effect — like with coyotes. Why is that?

A big part is that emotions shape our interactions with animals. The first time a new animal shows up in an urban environment, people often react with surprise and sometimes fear. But emotions aren’t really indicative of what they are actually doing. When we see a black bear on the outskirts of a city, for example, we tend to think it’s lost or stranded [instead of] maybe taking advantage of the habitat.

These animals, though, aren’t just responding to us directly but to things we’re doing to the environment. The removal of apex predators like wolves and pumas has enabled creatures like coyotes to become the top dogs of the American landscape in many regions, even as we tried to control them. We got rid of 10 wolves, and in return in some areas, we got a hundred coyotes.

Over time, assuming that there aren’t too many kinds of negative incidents, people get used to them. In cities like Chicago, where there are large numbers of coyotes and low numbers of conflict incidents, people have really embraced these animals and come to see them as normal or even natural parts of their environment.

What is a better way to understand wildlife in our cities as we continue to coexist?

Whether we’re talking about rats or black bears, which many people perceive as being really, really different, what are the qualities that they have? Most of them are omnivores and habitat generalists, meaning even in their historic natural environments, they inhabit a lot of different kinds of ecosystems. Many of them care for their young. Many of them are curious; they learn lessons and pass on their knowledge to other members of their group. If you add all these things up together, what does that sound like?

Humans?

Exactly! People don’t want to hear that there are so many rats in cities because rats are kind of like us, and have some of the same fundamental biological qualities that make humans so successful.

And so it’s good to remember that we’re all inhabiting the same environments in many cases because there are at least a few things that we have in common.

What does that mean, then, for how cities should approach wildlife management going forward?

This goes back to the legacy of that key period in the early 20th century, when people were thinking about what modern cities should be. In cities, we tend to think of wildlife, if at all, in terms of pest control.

But what if we thought about wildlife in terms of conservation? What kinds of habitats do we want to create, and what kinds of creatures do we want to surround ourselves with? To do that, we need to think about reorienting pest control toward habitat management and not so much just like lethal control. We need to think about the fact that our agencies don’t really have good mechanisms for including wildlife in their decision-making processes.

And on an individual basis, people are doing kind of crowdsourced wildlife management all the time, and they just don’t know it. If you’re planting trees around your home, you are repelling some creatures and inviting others. If you’re going twice the speed limit, you’re increasing the risk that some species are going to die on the roads. If we account for these creatures more often, it would probably create a better, healthier environment for them and for us.

Original article here

In 1905, the 26-year-old Albert Einstein proposed something quite outrageous: that light could be both wave or particle. This idea is just as weird as it sounds. How could something be two things that are so different? A particle is small and confined to a tiny space, while a wave is something that spreads out. Particles hit one another and scatter about. Waves refract and diffract. They add on or cancel each other out in superpositions. These are very different behaviors.

In 1905, the 26-year-old Albert Einstein proposed something quite outrageous: that light could be both wave or particle. This idea is just as weird as it sounds. How could something be two things that are so different? A particle is small and confined to a tiny space, while a wave is something that spreads out. Particles hit one another and scatter about. Waves refract and diffract. They add on or cancel each other out in superpositions. These are very different behaviors. Brian was just a kid when he first saw the movie Good Will Hunting and wasn’t thinking about therapy or his mental health. The 29-year-old engineer was mostly just fascinated by stories about repressed geniuses and Matt Damon’s background story of being a Harvard dropout. He also thought it was pretty rad that the original script was intended to be a spy-thriller.

Brian was just a kid when he first saw the movie Good Will Hunting and wasn’t thinking about therapy or his mental health. The 29-year-old engineer was mostly just fascinated by stories about repressed geniuses and Matt Damon’s background story of being a Harvard dropout. He also thought it was pretty rad that the original script was intended to be a spy-thriller.