One of the bigger lessons I got from reading Cal Newport’s book, Digital Minimalism, was the importance of scheduling your leisure time.

Scheduling time for hobbies may sound unnecessary. Aren’t those the things you do for fun?

Yet, I would wager that most of us have activities we’d like to do on the side but never seem to have time for:

- Learning a language

- Art

- Sports and activities

- Reading for fun

- Creating something

A common way to look at this state of affairs is to argue that we don’t have time for these things because we’re too busy. We want to relax at the end of a hard day, with whatever meager hours are left over.

This idea assumes we mostly use our time wisely, and if there isn’t time for something at the end of the day, it must be because there wasn’t time for it to begin with.

Where Does Your Free Time Really Go?

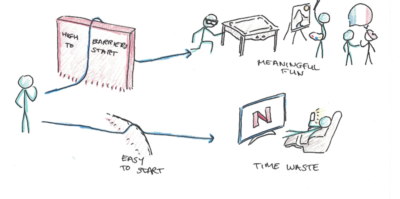

The view put forth by Newport in his book is that we tend to invest a lot of our time on various, low-value leisure activities that neither give us meaning or much enjoyment. Think television, Netflix, video games, social media and web surfing.

These activities often don’t provide much value, but they have really low barriers to get started. That combined with carefully engineered reward mechanisms keep them occupying our attention for many hours in the day.

In this view, it’s not that we don’t have time for high-quality pastimes because we’re too busy. Rather it’s because the default is to do something less worthwhile. If we could momentarily push ourselves out of these bad habits and onto something else, we’d be happier overall.

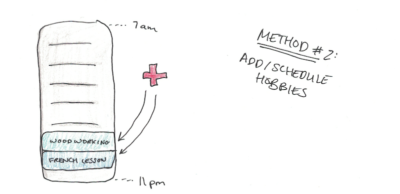

The solution is simply to schedule time for activities you care about.

How I’ve Been Applying This Idea

There’s two ways I’ve been working to integrate this idea more in my own life:

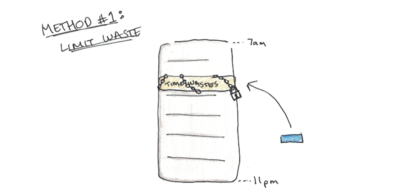

The first is to set strict limits on internet and television use, outside of a few high-quality areas. Right now I have LeechBlock configured on my phone to block my biggest time-wasting websites if I use them more than an thirty minutes per day total. I also have ten minute blocks on my iPhone per day for YouTube and other apps that I mostly use to waste time.

Thirty minutes per day is still more than enough time to follow everything I care about.

The second way I’ve been trying to integrate this idea is proactively scheduling time for higher-value hobbies. Making a goal to do some activity every evening, Monday to Thursday, whether it’s learning salsa, painting, attending a Chinese language meetup or going to the gym with friends, makes me less likely to fall back into binge-watching old television shows before going to sleep.

What If You Really Don’t Have Time?

The idea of scheduling hobbies tends to provoke one of two reactions:

The first comes from people who don’t like the idea of putting in effort to have fun. Why should you schedule fun–shouldn’t it be spontaneous?

However, I think the problem is often that there are barriers to starting activities you’d find really meaningful and enjoyable in your life, so the path of least resistance is usually not the most satisfying. Scheduling is just one way to avoid this trap.

The second reaction comes from people who argue they actually don’t have any time for hobbies. They’re truly too busy to do any of those things, since they work eighty hours per week, have seven kids and are studying for a dozen exams.

It’s hard to respond to this second objection because, there really are people in such a situation. You may even be in this situation yourself.

However, I also know that some of the highest-achieving, busiest people I know, nonetheless put in a lot of time in high-quality leisure activities.

Do You Really Lack Time, or Are You Just Stressed and Tired?

This suggests to me that the feeling that you have no time is often a reflexive evaluation about the amount of stress and exhaustion you experience to do the things you have to do in life, rather than an objective assessment about the number of hours per day you have no choice over.

My guess is that for most people in this situation, if you did a timelog, you’d find there’s lots of “wasted” time, and that your self-assessment mostly reflects the fatigue and stress you feel.

However, if it truly is fatigue and stress, rather than genuine lack of time, then that’s all the more reason to invest in high-quality hobbies. It’s the meaningless web surfing and Netflix binging that can make your life feel like a complete grind. Creating, learning, adventuring, socializing and experiencing are ways to reduce that stress and fatigue.

Therefore, paradoxically, I think it’s often the very people who claim they cannot possibly schedule their hobbies that need to do it most.

Original post here

Medicine is not the only field where left-right errors can make the difference between life and death: it’s possible that a steersman turning the ship right instead of left was a contributing factor in the sinking of the Titanic.

Medicine is not the only field where left-right errors can make the difference between life and death: it’s possible that a steersman turning the ship right instead of left was a contributing factor in the sinking of the Titanic. The idea is not to turn failure into success, per se, but to be open to what our failures have to teach us about who we are and who we aim to be. There may be a “success” inside the failure that you’re not seeing…

The idea is not to turn failure into success, per se, but to be open to what our failures have to teach us about who we are and who we aim to be. There may be a “success” inside the failure that you’re not seeing…

For most of my adult life, exercise was an ordeal. Even mild workouts felt grueling and I left the gym in a fouler mood than when I’d arrived. The very idea of the runner’s high seemed like a cruel joke.

For most of my adult life, exercise was an ordeal. Even mild workouts felt grueling and I left the gym in a fouler mood than when I’d arrived. The very idea of the runner’s high seemed like a cruel joke.