The good life is the simple life. Among philosophical ideas about how we should live, this one is a hardy perennial; from Socrates to Thoreau, from the Buddha to Wendell Berry, thinkers have been peddling it for more than two millennia. And it still has plenty of adherents. Magazines such as Real Simple call out to us from the supermarket checkout; Oprah Winfrey regularly interviews fans of simple living such as Jack Kornfield, a teacher of Buddhist mindfulness; the Slow Movement, which advocates a return to pre-industrial basics, attracts followers across continents.

The good life is the simple life. Among philosophical ideas about how we should live, this one is a hardy perennial; from Socrates to Thoreau, from the Buddha to Wendell Berry, thinkers have been peddling it for more than two millennia. And it still has plenty of adherents. Magazines such as Real Simple call out to us from the supermarket checkout; Oprah Winfrey regularly interviews fans of simple living such as Jack Kornfield, a teacher of Buddhist mindfulness; the Slow Movement, which advocates a return to pre-industrial basics, attracts followers across continents.

Through much of human history, frugal simplicity was not a choice but a necessity – and since necessary, it was also deemed a moral virtue. But with the advent of industrial capitalism and a consumer society, a system arose that was committed to relentless growth, and with it grew a population (aka ‘the market’) that was enabled and encouraged to buy lots of stuff that, by traditional standards, was surplus to requirements. As a result, there’s a disconnect between the traditional values we have inherited and the consumerist imperatives instilled in us by contemporary culture.

In pre-modern times, the discrepancy between what the philosophers advised and how people lived was not so great. Wealth provided security, but even for the rich wealth was flimsy protection against misfortunes such as war, famine, disease, injustice and the disfavour of tyrants. The Stoic philosopher Seneca, one of the richest men in Rome, still ended up being sentenced to death by Nero. As for the vast majority – slaves, serfs, peasants and labourers – there was virtually no prospect of accumulating even modest wealth.

Before the advent of machine-based agriculture, representative democracy, civil rights, antibiotics and aspirin, just making it through a long life without too much suffering counted as doing pretty well. Today, though, at least in prosperous societies, people want and expect (and can usually have) a good deal more. Living simply now strikes many people as simply boring.

Yet there seems to be growing interest, especially among millennials, in rediscovering the benefits of simple living. Some of this might reflect a kind of nostalgia for the pre-industrial or pre-consumerist world, and also sympathy for the moral argument that says that living in a simple manner makes you a better person, by building desirable traits such as frugality, resilience and independence – or a happier person, by promoting peace of mind and good health, and keeping you close to nature.

These are plausible arguments. Yet in spite of the official respect their teachings command, the sages have proved remarkably unpersuasive. Millions of us continue to rush around getting and spending, buying lottery tickets, working long hours, racking up debt, and striving 24/7 to climb the greasy pole. Why is this?

One obvious answer is good old-fashioned hypocrisy. We applaud the frugal philosophy while ignoring its precepts in our day-to-day lives. We praise the simple lifestyle of, say, Pope Francis, seeing it as a sign of his moral integrity, while also hoping for and cheering on economic growth driven, in large part, by a demand for bigger houses, fancier cars and other luxury goods.

But the problem isn’t just that our practice conflicts with our professed beliefs. Our thinking about simplicity and luxury, frugality and extravagance, is fundamentally inconsistent. We condemn extravagance that is wasteful or tasteless and yet we tout monuments of past extravagance, such as the Forbidden City in Beijing or the palace at Versailles, as highly admirable. The truth is that much of what we call ‘culture’ is fuelled by forms of extravagance.

Somewhat paradoxically, then, the case for living simply was most persuasive when most people had little choice but to live that way. The traditional arguments for simple living in effect rationalise a necessity. But the same arguments have less purchase when the life of frugal simplicity is a choice, one way of living among many. Then the philosophy of frugality becomes a hard sell.

Somewhat paradoxically, then, the case for living simply was most persuasive when most people had little choice but to live that way. The traditional arguments for simple living in effect rationalise a necessity. But the same arguments have less purchase when the life of frugal simplicity is a choice, one way of living among many. Then the philosophy of frugality becomes a hard sell.

That might be about to change, under the influence of two factors: economics and environmentalism. When recession strikes, as it has done recently (revealing inherent instabilities in an economic system committed to unending growth) millions of people suddenly find themselves in circumstances where frugality once again becomes a necessity, and the value of its associated virtues is rediscovered.

In societies such as the United States, we are currently witnessing a tendency for capitalism to stretch the distance between the ‘have lots’ and the ‘have nots’. These growing inequalities invite a fresh critique of extravagance and waste. When so many people live below the poverty line, there is something unseemly about in-your-face displays of opulence and luxury. Moreover, the lopsided distribution of wealth also represents a lost opportunity. According to Epicurus and the other sages of simplicity, one can live perfectly well, provided certain basic needs are satisfied – a view endorsed in modern times by the psychologist Abraham Maslow’s ‘hierarchy of needs’. If correct, it’s an argument for using surplus wealth to ensure that everyone has basics such as food, housing, healthcare, education, utilities and public transport – at low cost, rather than allowing it to be funneled into a few private pockets.

However wise the sages, it would not have occurred to Socrates or Epicurus to argue for the simple life in terms of environmentalism. Two centuries of industrialisation, population growth and frenzied economic activity has bequeathed us smog; polluted lakes, rivers and oceans; toxic waste; soil erosion; deforestation; extinction of plant and animal species, and global warming. The philosophy of frugal simplicity expresses values and advocates a lifestyle that might be our best hope for reversing these trends and preserving our planet’s fragile ecosystems.

Many people are still unconvinced by this. But if our current methods of making, getting, spending and discarding prove unsustainable, then there could come a time – and it might come quite soon – when we are forced towards simplicity. In which case, a venerable tradition will turn out to contain the philosophy of the future.

Original article here

As a teenager, I remember being moved almost to tears by the sound of a family member chewing muesli. A friend eating dumplings once forced me to flee the room. The noises one former housemate makes when chomping popcorn mean I have declined their invitations to the cinema for nearly 20 years.

As a teenager, I remember being moved almost to tears by the sound of a family member chewing muesli. A friend eating dumplings once forced me to flee the room. The noises one former housemate makes when chomping popcorn mean I have declined their invitations to the cinema for nearly 20 years. Only about 14% of the UK population are aware of misophonia, according to the King’s College London paper. Perhaps one of the reasons, Gregory suggests, is simply that it is hard to talk about. “You are essentially telling someone: ‘The sound of you eating and breathing – the sounds of you keeping yourself alive – are repulsing me.’ It’s really hard to find a polite way to say that.” Maybe the movie Tár will help: its protagonist, played by Cate Blanchett, has an extreme reaction to the sound of a metronome.

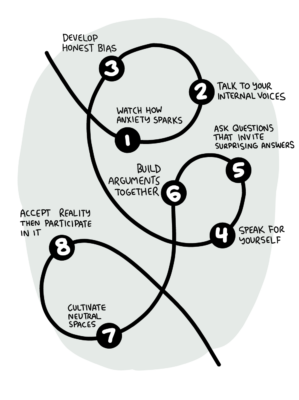

Only about 14% of the UK population are aware of misophonia, according to the King’s College London paper. Perhaps one of the reasons, Gregory suggests, is simply that it is hard to talk about. “You are essentially telling someone: ‘The sound of you eating and breathing – the sounds of you keeping yourself alive – are repulsing me.’ It’s really hard to find a polite way to say that.” Maybe the movie Tár will help: its protagonist, played by Cate Blanchett, has an extreme reaction to the sound of a metronome. Count me as a Buster Benson fan. His 2016 Cognitive bias cheat sheet is legendary among behavioral designers. I have a framed print out of his codex in my home and I’ve enjoyed his writing on various topics for years. He has extensive experience building products that move people at Slack, Twitter, and Habit Labs.

Count me as a Buster Benson fan. His 2016 Cognitive bias cheat sheet is legendary among behavioral designers. I have a framed print out of his codex in my home and I’ve enjoyed his writing on various topics for years. He has extensive experience building products that move people at Slack, Twitter, and Habit Labs. Most people tell you to write a book about what you know. I’ve had a career that has put me in the middle of resolving disagreements for several decades now, but I have to admit that when I came to this book it wasn’t because I had all the answers, but exactly the opposite: I deeply needed these answers, and didn’t know how or where to find them.

Most people tell you to write a book about what you know. I’ve had a career that has put me in the middle of resolving disagreements for several decades now, but I have to admit that when I came to this book it wasn’t because I had all the answers, but exactly the opposite: I deeply needed these answers, and didn’t know how or where to find them.