An estimated 23.5 million Americans, including my husband, suffer from an autoimmune condition — and their numbers are growing, though researchers don’t know why. You’ve likely heard of the most common autoimmune diseases — including type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, lupus, celiac disease, psoriasis, inflamatory bowel disease and Crohn’s disease — but you might be unaware that there are more than 80 named but lesser-known types. Through working as a nutritionist and living with my husband, I’ve learned the importance of diet in battling these disorders.

An estimated 23.5 million Americans, including my husband, suffer from an autoimmune condition — and their numbers are growing, though researchers don’t know why. You’ve likely heard of the most common autoimmune diseases — including type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, lupus, celiac disease, psoriasis, inflamatory bowel disease and Crohn’s disease — but you might be unaware that there are more than 80 named but lesser-known types. Through working as a nutritionist and living with my husband, I’ve learned the importance of diet in battling these disorders.

What is an autoimmune disease?

A healthy immune system can plainly distinguish between a foreign invader and its own body. When something inhibits the immune system’s ability to decipher what is safe and what is dangerous to the body, the immune system can attack its own healthy cells and tissues believing that they are threatening. This self-attack is an autoimmune condition.

What causes an immune system to attack its own healthy cells is still largely unknown but according to the National Institutes of Health, “There is a growing consensus that autoimmune diseases likely result from interactions between genetic and environmental factors.” There are studies that show that certain genes can predispose a person to certain autoimmune diseases, and this is why many autoimmune diseases show up in one family, as they do in my husband’s family where vasculitis, rheumatoid arthritis and alopecia all reside.

Yet simply having the gene doesn’t guarantee someone will get the disease. The gene is like fire kindling; there must also be a spark — or an environmental trigger — for there to be a blaze. Known triggers are infections, exposure to environmental toxins, hidden allergens, or stress and lack of sleep. Autoimmune conditions are like embers of a fire that never fully burns out. After the initial blaze, they can flare up again and again. We try to keep my husband’s condition tamped down through diet and exercise.

How a healthy lifestyle helps

Studies suggest that a healthy lifestyle can help keep the immune system balanced while less healthy situations can trigger the immune system to overreact. For instance, low vitamin D levels have been shown to be a risk factor for multiple sclerosis. Obesity has been linked to many autoimmune diseases, including MS, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Stress and anxiety have been shown to cause all kinds of autoimmune flares. On the other hand, anti-inflammatory dietary choices can lessen rheumatoid arthritis. Getting the right nutrients, maintaining a healthy weight, managing stress and sleeping regularly can help prevent an autoimmune flare.

“It is current knowledge that nutrition, the intestinal microbiota, the gut mucosal immune system, and autoimmune pathology are deeply intertwined,” reads a 2014 study, entitled “Role of ‘Western Diet’ in Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases” and published in the journal Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. In other words, what we eat and the health of our digestive tract are directly connected to our autoimmune system. Other studies suggest that autoimmune issues can be managed by healing a damaged gut.

Think of the gut as the front line of defense in an army. It is the first location that foreign and potentially dangerous substances deeply interact with our bodies. This is likely why almost 70 percent of our immune system lies in and around our gut so that it can react when poisonous, dangerous, allergic or toxic things enter our systems.

Since the gut is so directly tied to the immune system and healing a damaged gut can potentially manage an autoimmune condition, it seems important to keep yours healthy. You can do this by cutting out foods that inflame the gut, limiting unnecessary medications that can alter the bacteria balance in the gut and consuming prebiotics (such as artichokes and asparagus), probiotics (such as kimchi and miso) and bone broth to build a healthy mix of bacteria.

Anti-inflammatory food choices

The following foods have been shown to cause inflammation so should be avoided if trying to balance the immune system and keep inflammation under control:

- Sugar

- Refined carbohydrates

- Trans-fats

- Omega 6 fatty acids

- Processed foods and meat

- Alcohol

- Caffeine

- Artificial sweeteners

- Food dyes

The following foods have been shown to reduce inflammation:

- Leafy greens

- Fruits such as blueberries, strawberries and blackberries

- Fatty fish, high in omega 3 fatty acids

- Olive oil

- Avocados

- Nuts and seeds (if not allergic)

- Herbs and spices such as turmeric, cumin and garlic

- Vitamin D has been shown to help prevent inflammation and autoimmunity

When my husband was diagnosed, his doctors checked for underlying infections and allergies. When they didn’t find a specific trigger, he went on a strict anti-inflammatory diet for eight weeks. He took fish oil, vitamin D, vitamin C and zinc, and he did yoga, exercised regularly and got a lot more sleep than he usually did. These actions helped his body heal and not long afterward he was back throwing a baseball with our boys feeling like his energetic self. He’s only had one flare-up since, and it followed a few weeks of travel that affected his sleep patterns and stress levels. We will never know what sparked the wildfire, but we are forever thankful to know what tames it.

Original article here

Whenever I am faced with life’s uncertainty, I ask myself the following questions: Why is this happening? What can I do to make it go away? How can I navigate this effectively? What can I learn from this experience?

Whenever I am faced with life’s uncertainty, I ask myself the following questions: Why is this happening? What can I do to make it go away? How can I navigate this effectively? What can I learn from this experience? The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system.

The chorus of the theme song for the movie Fame, performed by actress Irene Cara, includes the line “I’m gonna live forever.” Cara was, of course, singing about the posthumous longevity that fame can confer. But a literal expression of this hubris resonates in some corners of the world—especially in the technology industry. In Silicon Valley, immortality is sometimes elevated to the status of a corporeal goal. Plenty of big names in big tech have sunk funding into ventures to solve the problem of death as if it were just an upgrade to your smartphone’s operating system. The researchers also found that with age, the body’s response to insults could increasingly range far from a stable normal, requiring more time for recovery. Whitson says that this result makes sense: A healthy young person can produce a rapid physiological response to adjust to fluctuations and restore a personal norm. But in an older person, she says, “everything is just a little bit dampened, a little slower to respond, and you can get overshoots,” such as when an illness brings on big swings in blood pressure.

The researchers also found that with age, the body’s response to insults could increasingly range far from a stable normal, requiring more time for recovery. Whitson says that this result makes sense: A healthy young person can produce a rapid physiological response to adjust to fluctuations and restore a personal norm. But in an older person, she says, “everything is just a little bit dampened, a little slower to respond, and you can get overshoots,” such as when an illness brings on big swings in blood pressure. Many people cheat on taxes — no mystery there. But many people don’t, even if they wouldn’t be caught — now, that’s weird. Or is it? Psychologists are deeply perplexed by human moral behavior, because it often doesn’t seem to make any logical sense. You might think that we should just be grateful for it. But if we could understand these seemingly irrational acts, perhaps we could encourage more of them.

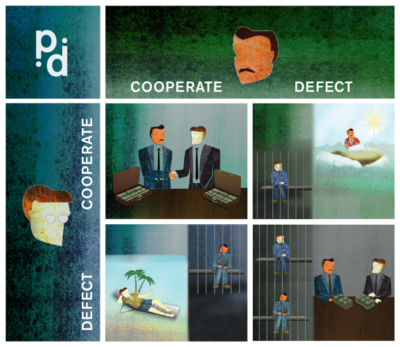

Many people cheat on taxes — no mystery there. But many people don’t, even if they wouldn’t be caught — now, that’s weird. Or is it? Psychologists are deeply perplexed by human moral behavior, because it often doesn’t seem to make any logical sense. You might think that we should just be grateful for it. But if we could understand these seemingly irrational acts, perhaps we could encourage more of them.

When it comes to getting people to cooperate more, Rand’s work brings good news. Our intuitions are not fixed at birth. We develop social heuristics, or rules of thumb for interpersonal behavior, based on the interactions we have. Change those interactions and you change behavior.

When it comes to getting people to cooperate more, Rand’s work brings good news. Our intuitions are not fixed at birth. We develop social heuristics, or rules of thumb for interpersonal behavior, based on the interactions we have. Change those interactions and you change behavior.