Quietly and with little fanfare, the idea of building new publicly owned housing for people across the income spectrum has advanced in the United States.

Governments have successfully addressed housing shortages through publicly developed housing in places like Vienna, Finland, and Singapore in the past, but these examples have typically inspired little attention in the US — which has more restrictive welfare policies and a bias toward private homeownership.

Then one US community started exploring social housing with a markedly more American twist: Leaders in Montgomery County, Maryland — a suburban region just outside Washington, DC, with more than 1 million residents — said they could increase their local housing supply not by ramping up European-style welfare subsidies but through essentially intervening in the traditional capitalist bidding process. Government, when it wants to, can make attractive bids.

Now, with an acute nationwide housing shortage, and declining home construction due to high interest rates, the idea is spreading, and more local officials have been moving forward with plans to create publicly owned housing. They are very clear about not calling it “public housing”: To help differentiate these projects from the typical stigmatized, income-restricted, and underfunded model, leaders have coalesced around calling the mixed-income idea “social housing” produced by “public developers.”

“What I like about what we’re doing is all we have effectively done is commandeered the private American real estate model,” Zachary Marks, the chief real estate officer for Montgomery County’s housing authority, told me in 2022. “We’re replacing the investor dudes from Wall Street, the big money from Dallas.”

By offering private companies more favorable financing terms, Montgomery County hoped to move forward with new construction that they’d own for as long as they liked. They had plans to build thousands of publicly owned mixed-income apartments by leveraging relatively small amounts of public money to create a revolving fund that could finance short-term construction costs. Eighteen months ago, this “revolving fund” plan was still mostly just on paper; no one lived in any of these units, and whether people would even want to live in publicly owned housing was still an open question.

Answers have since emerged: The first Montgomery County project opened in April 2023, a 268-unit apartment building called The Laureate, and tenants quickly came to rent. It’s not the kind of public housing most Americans are familiar with: It has a sleek fitness center, multiple gathering spaces, and a courtyard pool. “We’re 97 percent leased today, and it’s just been incredibly successful and happened so fast,” Marks said.

Encouraged by the positive response, Montgomery County has been barreling forward with other social housing projects, like a 463-unit complex that will house both seniors and families, and another 415-unit building across from The Laureate set to break ground in October. While construction has lagged nationwide as the Federal Reserve worked to rein in inflation, private developers in Montgomery County have been able to partner with the local government, enticed by their more affordable financing options.

Encouraged by the positive response, Montgomery County has been barreling forward with other social housing projects, like a 463-unit complex that will house both seniors and families, and another 415-unit building across from The Laureate set to break ground in October. While construction has lagged nationwide as the Federal Reserve worked to rein in inflation, private developers in Montgomery County have been able to partner with the local government, enticed by their more affordable financing options.

As word started to get around, city leaders elsewhere began reaching out, curious to learn about this model and whether it could help their own housing woes. Montgomery County was getting so many inquiries, they decided to host a convening in early November, inviting other officials — from places like New York City, Boston, Atlanta, and Chicago —to tour The Laureate and talk collectively about the public developer idea. Roughly 60 people were in attendance.

“I am very bought into the Zachary Marks’s line that there is every reason for cities to be building up a balance sheet of real estate equity and we should be capturing that and using it to reinvest in public goods,” said one municipal housing leader who attended the Montgomery County conference and spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to talk to the media. “That’s the vision — and you can just describe it in so many ways. You can say we’re socializing real estate value for public use, or you can describe it as we’re doing public-private partnerships to invest in our communities.”

Paul Williams, who leads the Center for Public Enterprise, a think tank supportive of social housing, said growing interest in the public developer model has even led to new conversations with the Department of Housing and Urban Development. “Public agencies are clearly hungry for tools that allow them to produce a lot more housing, and in the past year and a half we’ve gone from working with Montgomery County and Rhode Island to establishing a working group with a few dozen state and municipal housing agencies who come to our regular meetings,” he told Vox. “That’s gotten HUD’s attention, and we’re now talking with them about ways the federal government can support this kind of innovation.”

Atlanta’s leaders are on track to implement the Montgomery County model

Perhaps no city has run as fast with the Montgomery County idea than Atlanta, Georgia. The city’s mayor, Andre Dickens, took office in early 2022 and set an ambitious goal to build or preserve 20,000 affordable housing units within his eight-year term. The Dickens administration wanted to find ways to do this that didn’t depend on the whims of Republicans in the state legislature or federal government.

One of the key strategies Dickens’s team has embraced is making use of property the city already owns, such as vacant land. “We did not have a good sense of what we had, what we did not have, and what was the best use for any of it,” said Josh Humphries, a senior housing adviser to the mayor.

The Dickens administration convened an “affordable housing strike force” to get a better understanding of the city’s inventory and started studying affordable housing models around the world, including social housing in Vienna and Copenhagen. Atlanta leaders also participated in a national program called Putting Assets to Work and learned about the efforts in Montgomery County.

Humphries said what “really sealed the deal” on social housing for them was simply the scarcity of alternative tools to build affordable housing, since they were already exhausting all the available funding they had from the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC).

By the summer of 2023, armed with money from a city housing bond, the Atlanta Housing Authority’s board of commissioners voted to create a new nonprofit that would help build mixed-income public housing for the city. Leaders estimate it could lead to 800 new units by 2029.

Atlanta’s first bid for private-market developers to construct social housing went out last month, and Humphries says they’re excited about how their new financing could spark new partnerships. “The combination of tools that we plan to use that are similar to what they’re doing in Montgomery County, like being able to decrease property taxes and have better interest rates in your financing, is very enviable,” Humphries said. “It has allowed us to have conversations with market-rate developers who maybe otherwise wouldn’t be interested because they haven’t been able to figure out how to make their other [private-sector] projects work.”

Boston wants to move forward with social housing, and Massachusetts might help

Since 2017, Boston has been working to redevelop some of its existing public housing projects by converting them into denser, mixed-income housing. Kenzie Bok, who was tapped by the city’s progressive mayor last spring to lead the Boston Housing Authority, said that existing work helped pave the way for leaders to more quickly embrace the Montgomery County model. As in Atlanta, Bok and her colleagues have been trying to figure out how to build more affordable housing when they have no more federal tax credits available.

“I think everyone in the affordable housing community is looking around and saying, ‘Gee, we have this [low-income housing tax credit] engine for development but it doesn’t have capacity to meet the level we need,’” Bok told me. And while the federal government could increase the tax credit volume, that requires action in Washington, DC, that for years has failed to materialize.

Bok grew interested in the Montgomery County model since it seemed to offer a way for her city to augment its affordable housing production without Congress. Bok was also intrigued by the potential of the revolving fund to spur more market-rate construction in Boston, which has slowed not only because of rising interest rates but also because institutional investors typically demand such high rates of return.

“The default assumption is that affordable units are hard to build and market-rate ones will build themselves from a profit-motive perspective,” Bok said. “In fact, we have a situation now where ironically it’s often affordable LIHTC units that can get built right now and other projects stall out.”

Bok and her colleagues realized it’s not that mixed-income projects don’t generate profits — those profits just aren’t 20 percent or higher. Mixed-income affordable housing wouldn’t need to be produced at a loss, Boston leaders concluded, they just might not be tantalizing to certain aggressive real estate investors. By creating a revolving fund and leveraging public land to offer more affordable financing terms, Boston officials realized they could help generate more housing — both affordable and market-rate.

In January, in her State of the City address, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu pledged to grow the city’s supply of public housing units by about 30 percent in the next 10 years, with publicly owned mixed-income housing being one way to get there.

To help move things forward, state lawmakers are also exploring the idea. This past fall, Massachusetts’s governor put placeholder language in a draft housing bond bill to support social housing and a revolving fund. The specifics are likely going to be hashed out later this spring, but the governor’s bond bill is widely expected to pass.

In Rhode Island, too, state-level interest in supporting the notion of publicly developed affordable housing has grown. Stefan Pryor, the state’s secretary of housing, attended the Montgomery County, Maryland conference in November, and Rhode Island recently announced it would be contracting with the Furman Center, a prominent housing think tank at New York University, to study models of social housing. “We look forward to the study’s observations and findings,” Pryor told Vox.

Can mixed-income housing help those most in need?

Lawmakers intrigued by what Montgomery County is doing praise the fact that publicly owned mixed-income housing units theoretically offer affordable units to their communities forever, unlike affordable housing financed by the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit that can convert into market-rate rentals after 15 years. Leaders also like that after some initial upfront investment, the publicly owned projects start to pay for themselves, even delivering economic returns to the city down the line.

But while housing complexes like The Laureate can offer real relief to struggling middle-class tenants — a quarter of The Laureate’s units are restricted to those earning 50 percent or less of the area median income — an outstanding question is whether the social housing model could also help those who are lower-income, who might require even more deeply subsidized housing.

In Washington, DC, some lawmakers have been exploring the social housing idea, and one progressive council member introduced a bill calling to support mixed-income housing accessible to those making 30 percent or less of the area’s median income. But critics of the bill say that the rents of those living in nonsubsidized units would have to be so high to make that rental math work.

A housing official speaking on the condition of anonymity told me they think it’s okay if the social housing model can only really work to support more middle-class tenants in neighborhoods that charge higher rents because leaders still have financing tools to build more deeply affordable housing in lower-cost areas. In other words, social housing can grow the overall pie of affordable units throughout a city.

Other leaders, like in Boston and Atlanta, told me they’re exploring how they could “layer” the mixed-income social housing model with additional subsidies to make them more accessible to lower-income renters.

Marks, from Montgomery County, knows there’s still a lot of stigma and reservations about American public housing, which many perceive as being ugly, dirty, or unsafe. Few understand that many of the woes of existing public housing in the US have had to do with rules Congress passed nearly 100 years ago, such as restricting the housing to only the very poor. Besides getting his message out, Marks said he likes to just have people come see for themselves what’s being done.

“The temperature immediately comes down when people can walk around, see how attractive it is, how it’s clearly a high-quality community with nice apartments,” he said. “It’s why getting proof of concept is so important.”

Original article here

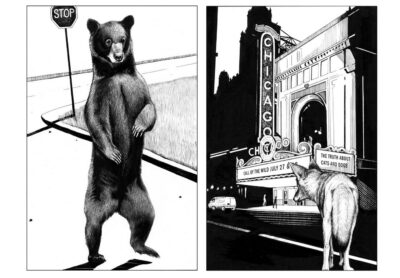

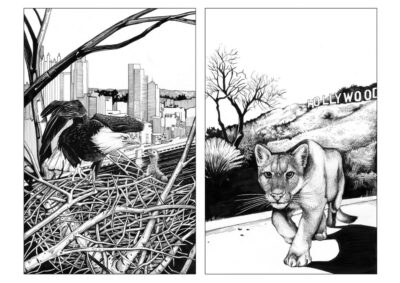

These domesticated animals then get cleared out by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading to this period from about 1920 to 1950 where there are fewer wild animals living in urban areas, particularly in North America, than really at any time before or since. This is a period in which some of the greatest thinkers about urban life were doing their writing, and almost everybody assumed that cities weren’t going to have animals in them.

These domesticated animals then get cleared out by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, leading to this period from about 1920 to 1950 where there are fewer wild animals living in urban areas, particularly in North America, than really at any time before or since. This is a period in which some of the greatest thinkers about urban life were doing their writing, and almost everybody assumed that cities weren’t going to have animals in them. But these examples are exceptions, not the rule. And this is very time-dependent: Although there are a small number of creatures that can adapt very quickly, for most others, this would take a long period of time — much longer than it takes for their populations to go extinct. And so the problem is [talking] about this as a solution to the fact that we’re rearranging and degrading ecosystems in ways that make the world a much harder place to live for the vast majority of species out there.

But these examples are exceptions, not the rule. And this is very time-dependent: Although there are a small number of creatures that can adapt very quickly, for most others, this would take a long period of time — much longer than it takes for their populations to go extinct. And so the problem is [talking] about this as a solution to the fact that we’re rearranging and degrading ecosystems in ways that make the world a much harder place to live for the vast majority of species out there. What happens when you close down a city street to cars? More people do non-driving things, like walking, biking, strolling, skating and frolicking in the space normally reserved for motor vehicles. Car-free advocates would say that as greenhouse gas emissions and traffic violence go down, happiness and connection go up — it’s hard to connect with your neighbors while ensconced in two tons of steel.

What happens when you close down a city street to cars? More people do non-driving things, like walking, biking, strolling, skating and frolicking in the space normally reserved for motor vehicles. Car-free advocates would say that as greenhouse gas emissions and traffic violence go down, happiness and connection go up — it’s hard to connect with your neighbors while ensconced in two tons of steel.